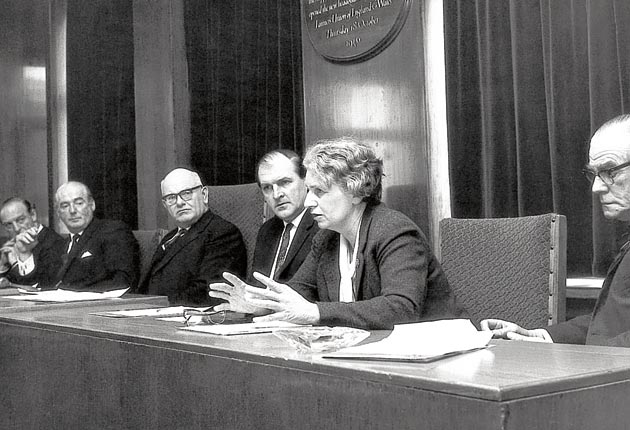

Mary Brancker: The first woman president of the British Veterinary Association

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mary Brancker was the first woman to become president of the British Veterinary Association since its foundation in 1881. When, in 1967, the president of the BVA was invited to attend the annual conference of the Norwegian veterinary association, the hosts were nonplussed to find that it was a woman who came to Oslo. She was the only female among delegates from all over Europe.

Mary, well used to being the sole woman in a male environment, remained confident and relaxed during rather strained introductions. The ice was well and truly broken, however, when on a sightseeing tour of the city she was shown a memorial to British servicemen who had died in the fight against Germany in the Second World War. Mary identified one of the names inscribed as that of her brother. The visit went on to be a great success

When she was elected president, Mary Brancker had been a veterinary surgeon for 30 years. She qualified from the Royal Veterinary College, London, at a time when women vets were rare indeed. She had a successful career in veterinary practice, doing pioneering work with exotic animals and virtually inventing the concept of veterinary care for fish farming. In parallel with her practice work, she was involved with the politics of her profession right from the beginning.

This early introduction to veterinary politics came about through her job as a young assistant in the practice of Harry Steele-Bodger in 1939. When war broke out and bomb damage forced the evacuation of the BVA from its London headquarters, the Association was run from the Lichfield practice of Steele-Bodger, who was president at the time. Many meetings were held there, Brancker being perforce involved. She recalled that when senior officials of the Ministry of Agriculture came to Lichfield to discuss arrangements for putting the veterinary profession on a war footing, she would pick them up from the station and drive through the black-out to return them afterwards.

One of the founder members of the Society of Women Veterinary Surgeons, she also took part in the activities of her local BVA branch; When Steele-Bodger died, tragically young, she took over his seat on the BVA council and control of a branch of his practice, in Sutton Coldfield; this remained her practice base for the rest of her career.

Through hard work, and with the advantage of a pleasing personality, Brancker's practice thrived, and so did her progress in the affairs of the BVA. She got on well with colleagues and was a popular choice when the Association broke the mould and elected her its first female president. It would be 2005 before another woman held that office.

Brancker's year of office coincided with the 1967-1968 outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease – the worst ever in the UK to that date. She was centrally involved in the task of marshalling vets to combat the disease, a traumatic exercise in which thousands of animals had to be examined and those found infected slaughtered and burned; Brancker rose to the challenge. She was awarded the OBE for her contribution in 1969.

After retiring from full-time practice, she remained as busy as ever. She pursued her interest in exotic animals, particularly primates, and helped found the British Veterinary Zoological Society. Never one to stick to the mainstream, she had a particular affection for zebras, the Zebra Foundation being another organisation which benefited from her support. The invertebrate world did not escape her care; spiders and beetles fascinated her, so of course, there had to be a Veterinary Invertebrate Society. When fish farming became a commercial activity, Brancker found her knowledge sought after and she promoted the profession's concern with the species. She was instrumental in obtaining a Nuffield Trust grant to set up the Institute of Aquaculture at Stirling University.

The BVA gave her its two highest awards: the Dalrymple Champneys Cup and the Chiron Award for outstanding services to the veterinary profession; she was made CBE in 2000 for services to animal health and welfare. She was elected FRCVS in 1977 and presented with an honorary doctorate by Stirling in 1996.

Mary Brancker saw her profession change from male domination to one in which women predominate. She participated in the winding-up of the Society of Women Veterinarians, which she had helped to found in 1941, in 1990 because such an organisation, formed to promote women vets' interests, was no longer necessary.

In her 96th year, Mary Brancker was still taking part in her profession's activities, a popular figure at any function she attended; only a few weeks before her death she enjoyed herself immensely at a BVA past-presidents' dinner in London. She had a long lifetime during which she made an outstanding contribution to her chosen calling.

Edward Boden

Winifred Mary Brancker, veterinary surgeon: born London 19 August 1914; FRCVS 1977; CBE 2000; died Sutton Coldfield, West Midlands 18 July 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments