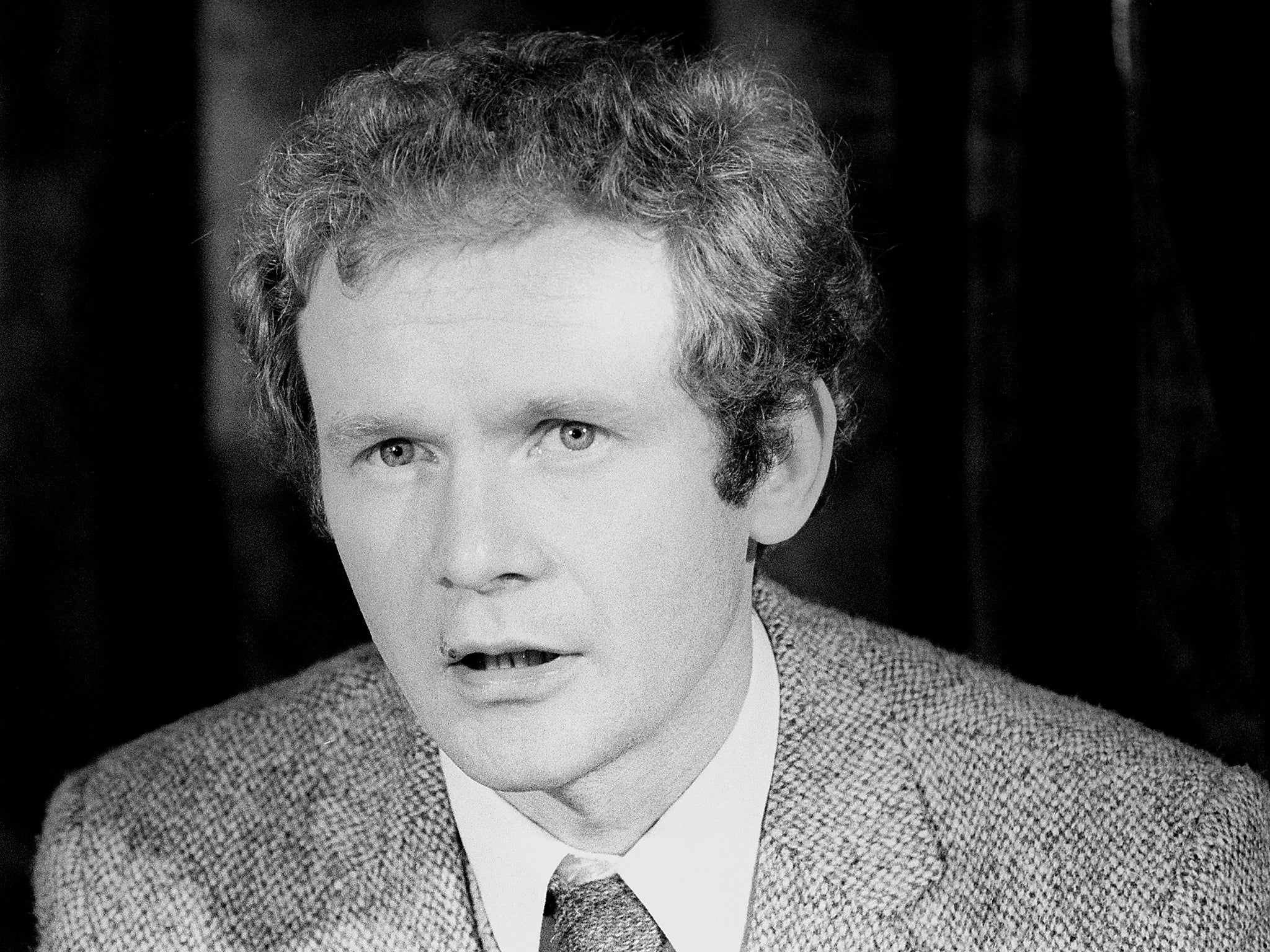

Martin McGuinness obituary: IRA commander turned politician who resisted British rule through violence and democracy

McGuinness was prepared to bomb and kill to drive the British out, but he was also an incorruptible, church-going Catholic and a loyal family man

Martin McGuinness, the IRA commander turned republican politician, was unusually free from the kind of vanity common among public figures, but would sometimes react angrily to things written about him.

In his book, Rebel Hearts, the British journalist Kevin Toolis described McGuinness as a zealot, whose followers bombed the commercial centre of his home town, Derry, until it looked like a war zone, and who “implicitly endorsed what can only be described as needless cruelties”.

He mentioned Marta Doherty, tarred and feathered, with her head shaven, for being engaged to a British soldier, and Joanna Matthews, murdered solely because she was collecting forms for a census the IRA was boycotting. Toolis also witnessed a verbal confrontation between McGuinness and fifteen heavily armed British soldiers.

After the book’s publication, the author had a telephone call from an aggrieved McGuinness. He was not angry at being portrayed as a man steeped in political violence, but that Toolis had alleged that he called the British soldiers “fuckers“. “I never used that word!” he protested.

McGuinness was prepared to bomb and kill to drive the British out, but he was also an incorruptible, church-going Catholic and a loyal family man, a combination that made him one of the most dangerous enemies the British state ever had.

Born in 1950, the oldest of seven children, in the heavily Catholic Bogside district of Derry – known to Protestants as Londonderry – McGuinness might have lived the ordinary life of a skilled working man had he grown up in a less divided community.

His father was a welder, his brothers were bricklayers and carpenters. He left school at 15 to work as a butcher’s assistant. His law-abiding parents, William and Peggy, were horrified when they found an IRA beret in their teenage son’s bedroom.

His involvement in violence began when Derry erupted in riots after the Royal Ulster Constabulary had baton-charged a civil rights march in 1968. The 18-year-old would go out during his lunch break and again after work to hurl stones at the police.

Then his anger was directed at the province’s unionist administration and the RUC. Later it shifted to the British state. By the end of 1970, he had joined the newly created Provisional IRA, a very much more effective and dangerous organisation than the half-defunct Official IRA.

More than 100 people died in the political violence in Derry between 1971 and 1973, including 54 members of the security forces.

Within this deadly organisation, McGuinness stood out for his physical courage and a quiet air of authority that commanded respect.

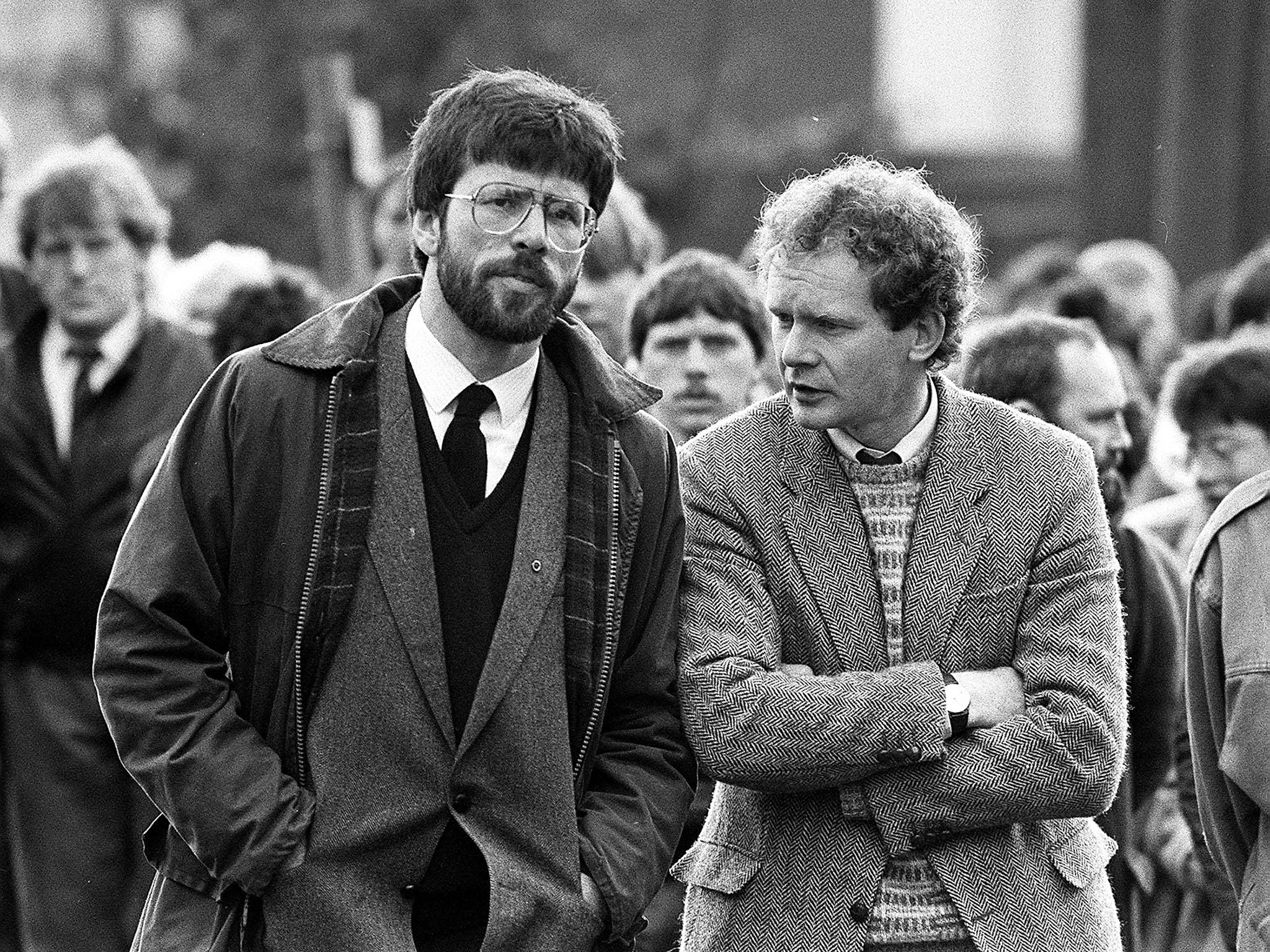

As head of the IRA in Derry, aged only 22, he was part of a seven-man delegation flown on 7 July 1972 to a secret meeting with the Home Secretary, William Whitelaw, at the home of millionaire Tory minister Paul Channon in London’s Cheyne Walk, overlooking the Thames. Another delegate was the 23-year-old Gerry Adams.

The meeting collapsed as the IRA men refused to accept anything less than a rapid British withdrawal from Northern Ireland.

At this stage, McGuinness did not hide his IRA membership, for which he spent the larger part of 1973 and 1974 in prison in the Irish republic.

After 1974, he maintained that he was just a politician in the IRA’s political wing. He was never convicted of a terrorist offence in the north, but British intelligence believed that while living quietly on a Derry council estate with his wife, Bernadette, and four children, he was the IRA’s director of operations in 1976-78 and Chief of Staff in 1978-82.

The IRA’s gradual transformation from a terrorist group to a political movement would have been almost impossible without McGuinness’s involvement. Gerry Adams was the political strategist, but it was McGuiness whom the IRA gunmen respected and were prepared to follow.

He ceased being IRA Chief of Staff in 1982, after the IRA had been persuaded to adopt the strategy known as “the Armalite and the ballot box”, though his influence over the gunmen did not cease.

McGuinness was a candidate in every UK general election from 1983 to 2010, firstly in Foyle, and then Mid-Ulster, which he won in 1997 – though like all Sinn Fein MPs, he refused to be sworn in. He resigned from Parliament in January 2013.

He was Sinn Fein’s chief negotiator in the all-important talks that began in 1993 and finally brought peace to Northern Ireland through the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. The following year, by now a grandfather, he became minister for education in the newly created devolved administration.

Northern Ireland had retained the 11-plus exam decades after it had been abandoned in Britain and McGuinness, who was an 11-plus failure educated at a Catholic school run by the Christian Brothers, must have enjoyed abolishing it.

With the creation of the Northern Ireland Assembly in 2007, McGuinness was chosen by Sinn Fein to be Deputy First Minister, a post he held for nearly ten years. The First Minister was the Democratic Unionist, Ian Paisley.

The former IRA commander and the fire-and-brimstone Protestant preacher made one of the most unlikely pairings in political history. Curiously, they got on so well that they were nicknamed “the Chuckle Brothers”.

When Paisley died in 2014, McGuinness declared “our relationship confounded everybody … I have lost a friend”.

Another extraordinary upshot of the peace agreement was the sight of the former IRA commander greeting the Queen at Hillsborough Castle in 2016. He asked after her health, and she replied: “I’m still alive” – unlike, she might have added, her second cousin, Louis Mountbatten, killed by an IRA bomb when McGuinness was the organisation’s Chief of Staff.

His relations with subsequent first ministers were not so cordial. The gradual souring culminated in McGuinness’s refusal to work with the First Minister Arlene Foster, whom he held responsible for the expensively bungled attempt to convert the province to renewable energy.

He insisted that his decision to resign as Deputy First Minister, on 9 January, was political and not caused by ill health – but it soon emerged that he was seriously ill from amyloidosis, a rare disease that attacks the body’s organs.

He died on 21 March 2017 after being ill for several weeks with a rare heart condition.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks