A Life in Focus: Marcel Marceau, sculptor of silence whose name became synonymous with mime

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: Marcel Marceau, from Monday 24 September 2007

Lindsay Kemp, who died last week, was the protégé of the theatrical French master whose name was and remains synonymous with mime. Marcel Marceau’s obituary follows.

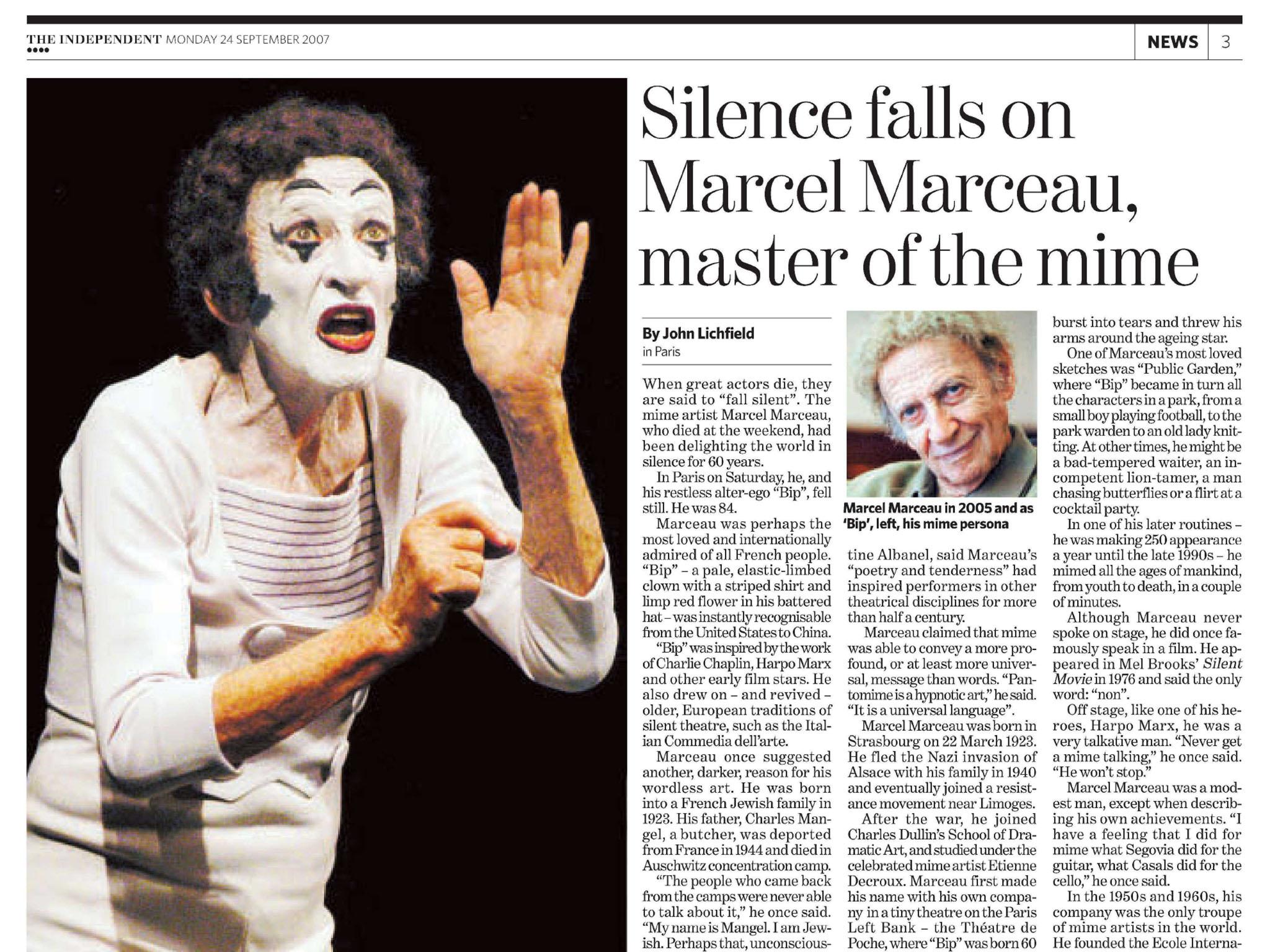

Wearing white trousers, a crumpled top hat adorned with a bedraggled red artificial flower and a striped vest with big buttons, and with a mask of a face that was able to suggest a thousand different impressions, the celebrated mime Marcel Marceau produced an astonishing variety of brief dramatic scenes and comical encounters with himself – The Cage, Walking Against the Wind, The Maskmaker, The Park, among others – and a gallery of unforgettable characters – head waiters, mad sculptors, matadors, dictators and ballet dancers.

Of Marceau’s moving depiction of the four ages of man, Youth, Maturity, Old Age and Death, one critic said, “He accomplishes in less than two minutes what most novelists cannot do in volumes.”

He was born Marcel Mangel, the son of a butcher, in Strasbourg in 1923. He attended schools in Strasbourg and Lille and even as a child was a gifted mimic of animals and human beings. He enjoyed the silent movies of the 1920s, in which his favourite stars were Buster Keaton, Harry Langdon, Stan Laurel and above all Charlie Chaplin (“To us, he was a god”), whom he was to meet later in life. Their films were silent, so they had to express their feelings through mime

They were perfect fakes, for Marcel Mangel, as both a Resistance spy and a Jew, was on the wanted list. The narks kept examining his papers and looking at his face, while he stared back at them without batting an eyelid, showing no trace of fear. The men were baffled, and let him go. It was an early demonstration of the powers of mime.

In 1945, he began attending Charles Dullin’s famous school of dramatic art in the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt, where he also followed classes given by Etienne Decroux, who had invented the system of “mime corporel” – corporeal mime. It became the basis for Mangel’s own art of facial and bodily control. One of his fellow students was Jean-Louis Barrault, who appreciated his exceptional talents as both actor and mime. Mangel became a member of Barrault’s own company and was cast in the role of Arlequin in the “mimodrama” Baptiste, a role Barrault had made famous in the 1945 film Les Enfants du Paradis.

Mangel was such a success that Barrault encouraged him to present his own mimodrama, Praxiteles and the Golden Fish (1946), at the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt. Its popularity made Mangel decide to embark upon the career of a mime. The stage name he chose was Marcel Marceau, taken from a line in a poem by Victor Hugo about a great general, Marceau-Desgraviers. But the character he created was “Bip”.

Marceau borrowed Bip’s name from the character of Pip in Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations and indeed Bip resembled the wan-faced waifs of Dotheboys Hall in Nicholas Nickleby. He had the woebegone orphan look of children in early silent movies, like Jackie Coogan in The Kid or Oliver Twist.

“Born in the imagination of my childhood,” Marceau once wrote of his greatest success, “Bip is a romantic and burlesque hero of our time. His gaze is turned not only towards heaven, but into the hearts of men.”

Marceau’s scenarios for his sketches were minimal, given body by his weird physical agility and an acute sense of “scenic time”. In 1949 he started his own mime company at the tiny Théâtre de Poche in Montparnasse. Its first performance, in 1951, was a mime drama based on Gogol’s tale The Overcoat. It was such a popular success that Marceau enlarged the company and produced classic period mime dramas including Pierrot de Montmartre (1952) and the more ambitious Le Mont de Piété (“The Pawn Shop”, 1956).

But unlike the “straight” theatre, mime in France has never enjoyed official financial sponsorship, so Marceau had on occasion to abandon his company and start to make a living on tour as Bip in celebrated solo turns.

He toured Europe for eight years. His big break in America came in 1955-56 and Marcel Marceau and mime became inextricably linked in the public mind across the world.

“Americans are like big children – they never lose their sense of amazement and wonder,” he once said of his transatlantic fans. “I show them something they have never seen before.”

Marceau’s beautiful Bip Hunts Butterflies had obviously influenced the great ballet dancer Jean Babilée when in the 1950s I saw him dancing in London in the ballet Le Papillon. Bip toured the whole world, to universal acclaim. He enchanted the Japanese, who after the war were still trying to learn foreign languages. They adored Bip because he was able to express every human feeling without words, and when I arrived in Japan in 1959 the Japanese were still under his spell.

By the end of his life, by Marceau’s reckoning he had toured in 65 countries. He gave a rare touch of originality to television shows and appeared in several films, including the cult sci-fi adventure Barbarella (1968), starring Jane Fonda (with Marceau in the role of Professor Ping) and Mel Brooks’s Silent Movie (1976), in which Marceau spoke the only line (in fact the only audible word), “Non!”

The list of Marceau’s prizes and academic honours is enormous. He was an Officier de la Légion d’honneur, Grand Officier de l’Ordre nationale du Mérite, Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres de la République Française, and received honorary doctorates from American universities including Princeton, Michigan and Columbia. Bip received a “Molière d’honneur” in Paris in 1999. And the city of Paris finally endowed the art of mime and Marcel Marceau with enough money to run a permanent school there.

Marcel Mangel (Marcel Marceau), mime: born Strasbourg, France 22 March 1923; Director, Compagnie de Mime Marcel Marceau 1949-64; Director, Ecole Internationale de Mimodrame de Paris Marcel Marceau 1978-2005; three times married (two sons, two daughters); died Paris 22 September 2007.

James Kirkup died in 2009

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks