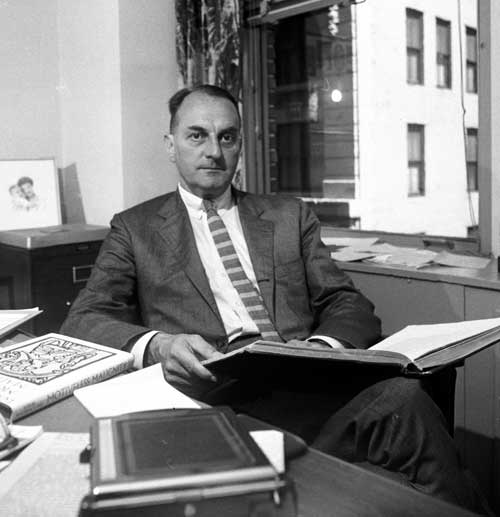

Louis Auchincloss: Writer who chronicled the lives and times of America's WASP elite

They are referred to as "white shoe" – the old-established companies and law firms of New York and New England, run by gentlemen conservatives of the old WASP elite; white, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant, and invariably very rich. Once this class ran America too, almost as a birthright. Times have changed, but in the pages of their fictional chronicler Louis Auchincloss, they and their well-bred offspring live for ever.

In fact, Auchincloss was one of them. His family had emigrated from Scotland at the start of the 19th century, and both his father and grandfather were Wall Street lawyers. Franklin Roosevelt was a third cousin, and Louis was related by marriage to Jackie Kennedy, who would work with him in her post-JFK, post-Ari Onassis incarnation as a book editor in Manhattan.

He attended the exclusive Groton School in Massachusetts, an American cross between Eton and Gordonstoun, founded in 1884 by the clergyman and great educator Endicott Peabody, widely seen as the model for the headmaster in The Rector of Justin, published in 1964 and widely regarded as Auchincloss's best novel. He then followed the conveyor belt of patrician upbringing to Yale, his ambitions already set on a literary life.

But after a first manuscript, about a New York socialite, was rejected, he decided that being a second-rate writer was not for him. Better the law that flowed in the family veins. Auchincloss dropped out of Yale a year before he was due to graduate, and instead took a degree at the University of Virginia Law School before joining the eminently white-shoe New York law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell, where he specialised in estate law.

From 1947, two careers melded as one. The weekday lawyer, dealing with the well-heeled and the disposal of their fortunes, turned into the weekend novelist, who transformed his experiences into elegant fiction. Out of deference to his mother, who felt his work was "vulgar and trivial" and might damage his prospects at Sullivan & Cromwell, his first novel, The Indifferent Children, appeared under a pseudonym in 1947. But the work was well reviewed, and thereafter Auchincloss produced some 60 novels, collections of short stories and biographies, at the rate of roughly one a year until his death.

He was a compulsive writer who once compared himself to Jack Kennedy and the former president's celebrated remark to Harold McMillan that if he didn't have a new girl every three days, he suffered from headaches. "I thought that was rather extreme," Auchincloss once told the Associated Press, "but writing is a little bit like that for me."

His world was one of New York mansions, country homes and Atlantic crossings by liner. Its ways, and its subtle pressures and vices – many of them related to money – were the raw material of his books. His eye for the distinctions between classes of affluence was acute. "If you were rich in New York, you lived in a house with a pompous beaux-arts facade and kept a butler and gave children's parties with spun sugar on the ice cream, and little cups of real silver as game prizes. But if you were not rich you lived in a brownstone with Irish maids who never called you 'master Louis,' and parents who hollered up and down the stairs instead of ringing bells."

Auchincloss managed to combine the law, his writing and his family almost effortlessly. He would alternate the first two as required, and always find time for the third – as a friend remembered, writing his novels in longhand on a legal pad in his antique- filled living room on Park Avenue, while his young sons played cowboys and Indians around him.

His writing perhaps never achieved the heights it might have. By his own admission, he could have taken more care revising his books. Some reviewers considered his characters shallow and untextured; others criticised him for an obsession with class. That last charge he always strenuously rejected. Great writers from Shakespeare to Proust had concentrated on the well-born, the rich and the powerful. "When people say your subject is limited," he once observed, "it's because they don't like it."

Auchincloss's style was restrained. He didn't write about sex and feats of derring-do. His novels were of manners, their theme the morality and virtues instilled by breeding and a proper education – what today might be called "standards", embodied in the motto of Groton and by extension the entire WASP establishment: "to serve is to rule".

His characters were often introspective, of no special distinction. Yet on occasion he could skewer them. Of one he wrote with withering disdain, "his moderate good looks, his moderate competence in sports, and his moderate good nature caused him to be moderately accepted."

Nor did Auchincloss particularly praise the rich. Indeed, his writing is infused with a sense of how money distorts and corrodes, of the pressures and strains it can cause. Above all he sought to explain. According to his friend Gore Vidal (whose stepfather was also an Auchincloss) few American writers have better explained the role of money in people's lives. He [Louis Auchincloss], Vidal said, was "the only one who tells us how our rulers behave in their banks and boardrooms, their law offices and their clubs."

Auchincloss finally left the law in 1987. Thereafter he served his city as one of his characters might have done: as chairman of the Museum of the City of New York, of City Hall Restoration Committee, and of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His final book, The Last of the Old Guard, appeared in 2008. To the end he remained a symbol of a seemingly vanished age: erect, well dressed and discerning, a living New York landmark.

In fact the WASPs, he liked to point out, had not disappeared; their lifestyle, at least until the crash of 2008, was more opulent than ever. But the old monopoly of power had gone, and the country was the poorer for it. "The tragedy of American civilization," Auchincloss wrote in 1980, "is that it has swept away WASP morality and put nothing in its place."

Rupert Cornwell

Louis Stanton Auchincloss, writer and lawyer: born Lawrence, New York 17 September 1917; married 1957 Adele Lawrence (died 1991; three sons); died New York City 26 January 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks