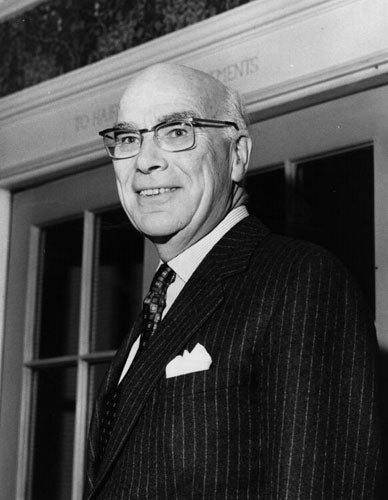

Lord Stokes: Tough industrialist unfairly blamed for the failure of Leyland's merger with the British Motor Corporation

Donald Stokes was chairman of the ill-fated British Leyland Motor Corporation from 1968 to 1975. He was unfairly blamed for the inevitable failure of the government-inspired attempt to bring together all the major British-owned motor companies in the British Leyland Motor Corporation in 1969, a task in which the greatest managerial genius could never have succeeded.

Stokes, personally sensible, engaging, unassuming, unpretentious, was far tougher, far abler, than the picture of the "over-promoted bus salesman" painted by his enemies. He knew he was not a major intellect but, as he once told me: "Sure, the civil servants I deal with are more intelligent than I am but I've got that little bit of cunning they lack." In fact he was far more of a salesman and deal-maker than a manager capable of running a complex group.

After attending Blundells, a minor public school which he left in 1930 at the age of 16 – "I hated school," he once said – Stokes gained a student apprenticeship at Leyland Motors, then a small, provincial truck-maker based in Leyland, near Preston, Lancashire.

He was soon promoted to head the company's export department, where he learnt to be tough. A defining moment came when he sacked an older man, a "good friend", who had been Stokes's superior. But "he was disastrous and I knew that if I didn't sack him he would ruin the department". So Stokes got rid of him, a traumatic decision during the Depression when jobs were hard to find. This first touch of decisiveness showed his mettle and remained a touchstone throughout his working life. "It was more than firing a man I liked. It meant deciding how I was going to live, the kind of person I was going to be."

The underlying toughness was reinforced by five wartime years in which Stokes rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. "I came back a different person," he once said. "In a few years the war made me what I am. It was like a quick survival course."

In the 15 years after his return to Leyland in 1946 Stokes made his name selling Leyland's lorries – and above all their buses – throughout the world. He thus made good his promise that he would export half the firm's output. He did, profitably, though the vehicles were neither very advanced, nor, in many cases, all that reliable. Fortunately for Stokes, most of the sales went to relatively undemanding Commonwealth markets, though he did achieve one well-publicised triumph in selling buses to Castro's Cuba in the teeth of the US embargo.

Nevertheless, throughout his career, Stokes was fully aware of the need to strengthen the company's position in continental Europe, markets largely barred to imports through the 1950s and much of the 1960s.

But it was in the 1960s that Stokes emerged as the boss of an ever-expanding empire. In 1963 he became managing director of Leyland, and soon afterwards won a battle for control of the firm with the chairman, Sir Henry Spurrier, a member of the family that had formerly been Leyland's biggest shareholders. Leyland had already acquired Associated Commercial Vehicles, makers of lorries and the AEC buses used in London and other big cities.

Until the arrival of competitive vehicles from Europe, the deal gave Leyland a virtual monopoly of the British bus market. Leyland had already made its first venture into car-making with the purchase of Standard-Triumph in Coventry, makers of a well-known, if not especially profitable range of cars including the Triumph sports cars. But Triumph, with an output of not much over 100,000 cars a year, was not big or specialised enough to be viable despite Stokes's attempts to impose what he called "our peculiar Lancashire ways", i.e. internal discipline and cost-cutting.

Throughout the 1960s the acquisitions continued, notably that of Rover, whose management was worried about being too small-scale a producer. The deal brought with it not only the Rover 2000, a direct competitor to Triumph's own 2000 model, but also Land Rover, which had the potential of being the most commercially competitive of all British vehicles world-wide.

But in 1969 came the long-anticipated Big One, the "merger" with the troubled British Motor Corporation, itself the result of a series of ill-digested takeovers in the years since Austin and Morris had merged in 1952. The management of BMC ranged from the appalling to the non-existent and naturally Stokes was put in charge, helped by John Barber, a former Ford executive.

From the start their hands were tied: although the Wilson government had acted as midwife to the deal through the Industrial Reorganisation Corporation, neither the Government nor the IRC were prepared to take the brutal, if logical step of allowing BMC to go into bankruptcy before the deal (as the Heath government did with Rolls-Royce a few years later).

Had they done so, a deal could have been done with the unions to rationalise the hundreds of different contracts in force in the group's sprawling mass of factories and to impose some form of industrial discipline on the workers and the shop stewards (though even then orderly planning would have been impossible given the regularity of strikes at crucial component suppliers which, in one six-month period, cost the firm 77,000 vehicles). To make matters worse, British Motor had virtually no forward plans for new models and no real idea as to the profitability or otherwise of existing models, a state of affairs that naturally shocked and even panicked Stokes and Barber.

Like the factories in which they were made, the model range of the combined group was a messy sprawl. British Motor brought with it a mass of brands – Austin, Morris, Riley, Wolseley, Jaguar and MG – as well as vans and heavier vehicles made at the troubled and never profitable Bathgate plant in Scotland. Leyland had trucks ranging up to the enormous tank transporters made by Scammell.

So Stokes and Barber had three impossible tasks: to tame the corporate baronies which operated as virtually separate companies; to try and devise a coherent model plan covering every type of vehicle, from the Mini to the heaviest of trucks; and, most impossible of all, to get the – permanently rebellious – workforce to work with the – often inadequate – management of individual factories. He and Barber at least managed to introduce some form of financial order into the chaos, albeit at the cost of over-centralisation, a policy Barber brought with him from Ford.

Stokes had clear and sensible ideas about the cars required, not overly cheap but "small, comfortable, fairly sophisticated, and capable of doing a lot of miles to a gallon of petrol". But to make them profitably he had to sideline BMC's resident design genius, Alec Issigonis, whose cars, most obviously the Mini, were too complex to be produced economically. Stokes replaced him with Triumph's technical director, Harry Webster, whose designs, like the Allegro, lacked the appeal of Issigonis' models – ironically the vehicle on which he was working at the time of the takeover, but then abandoned, a small car similar to the model Renault later produced as the Renault 5, could have helped the group enormously.

Not surprisingly British Leyland's financial situation deteriorated swiftly after the first oil shock of October 1973, the three-day week and the slump that followed. Stokes's reaction was typical: he tried to persuade the Shah of Iran to invest in BL, not a ridiculous idea at a time when the oil producers were bulging with cash after the oil crisis of 1973-74 and even Colonel Gaddafi was investing in Fiat.

In July 1974 Stokes had told Tony Benn, the Minister for Industry, that the group needed an additional £250m for capital investment but by the end of the year the Government had come to the conclusion that Stokes and Barber had to go. Stokes and Barber were the victims of an absurdly unrealistic plan put forward by the megalomaniac Lord Ryder of Eaton Hastings, who was acting not only as an adviser to the Government but also as chairman of the newly constituted Enterprise Board.

Ryder's plan envisaged no redundancies, £200m in equity finance provided by the Government – giving the Government a 65 per cent stake in the company, and £500m in loans to enable the group to expand – and to produce a new Mini by 1980. The plan, amended to provide up to £1.4bn in public money, was accepted by the Cabinet and although Tony Benn was blamed for the inevitable fiasco, the whole government was to blame.

The situation was so grim that within a few months the group had been reorganised and the Government had taken over at a price of a mere 10p a share, at a time when the only alternative was liquidation. Stokes, ever the canny negotiator, had offered to take a substantial pay-cut and had done well to get even 10p a share for a company on the verge of bankruptcy, although even then some of the shareholders balked at the price.

It was his last contribution to the group he had built up. He had become a scapegoat for failing to do the impossible. As one insider put it at the time, "Stokes is a dirty word with the Government. . . for five years after he left Leyland he was a tar baby: anyone who touched him was contaminated. Everyone blamed him. . . It was most unfair. Stokes was never up to the job, but it was the Labour government's failure, and Tony Benn's in particular."

Stokes was soon kicked upstairs to be president of BL, where he remained an impotent figure for four years watching the group decline even further into chaos and then recover partially under Michael Edwardes. In 1980, at the age of 64, Stokes retired and for the next decade he took on a variety of minor jobs, like the chairmanship of Jack Barclay, the Rolls-Royce and Bentley retailer. As late as 1990 he was called in to try and help Reliant, makers of the famous Robin, a sad finale to an otherwise largely distinguished career.

Nicholas Faith

Donald Gresham Stokes, industrialist: born 22 March 1914; exports manager, Leyland Motors (later Leyland Motor Corporation) 1946-50, general sales and service manager 1950-54, director 1954-63, managing director and deputy chairman 1963-67, chairman 1967; Kt 1965; chairman and managing director, British Leyland Motor Corporation 1968-75; created 1969 Baron Stokes; president, BL Ltd 1975-79; chairman, KBH Communications 1987-95; married 1939 Laura Lamb (died 1995; one son), 2000 Patricia Pascall; died 21 July 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks