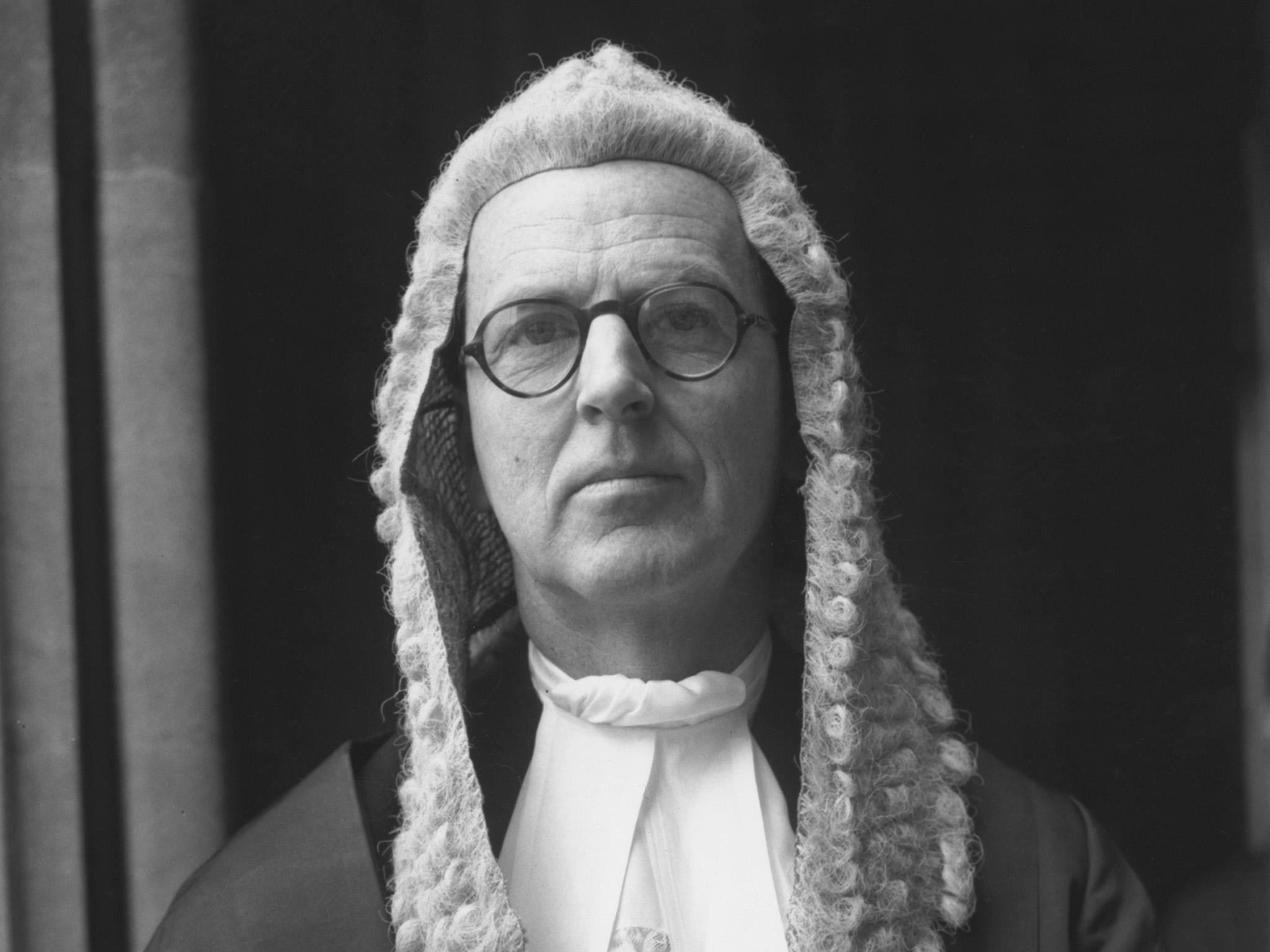

Lord Hutchinson: Barrister in Lady Chatterley trial who also defended Christine Keeler and Howard Marks

He lit stuffy courtrooms up with charm and humour rooting for his clients with vigour often against the very values of the Establishment

Jeremy Hutchinson, Lord Hutchinson, was no ordinary lawyer. He excelled as a silver-tongued goad to Britain’s society circles and a devilish advocate for spies and drug smugglers. He fought legal battles during the Sixties and Seventies that set important precedents for freedom of speech in this country.

Born into a wealthy family who dined with poet TS Eliot and members of Bloomsbury set, the peer, who has died aged 102, was among the last of Britain’s lawyer-celebrities: bewigged barristers whose courtroom performances rivalled those of showbiz for press attention.

He nearly matched the professional theatrics of his first wife, the actress Dame Peggy Ashcroft, captivating juries with a polished, mesmeric speaking style and lightly mocking judges as “old darling” – a habit that his friend, the actor John Mortimer, conferred on the character Horace the television series Rumpole of the Bailey.

Yet Lord Hutchinson’s talents were not used in support of the Establishment despite his role as Queen’s Counsel. He was a liberal who once made an unsuccessful attempt to run to become a Labour MP.

“He wanted to undermine the age of deference – whether deference to political masters or to censors – and to inject a certain amount of freedom into public life,” according to Thomas Grant QC, author of Jeremy Hutchinson’s Case Histories.

“At a time when the criminal advocate was not necessarily conceived as the most glamorous or important of occupations, he showed that it was an absolutely critical part of constitutional arrangements, a bulwark of law and civil liberties.”

Lord Hutchinson’s clients included Christine Keeler, the model convicted of perjury for her role in the Profumo affair in 1963, and the Soviet spies George Blake and John Vassall, for whom he unsuccessfully sought leniency.

He defended the late drug-smuggler-turned-author Howard Marks, making the successful, if to many observers questionable, argument that his client had been working for MI6. He was equally successful in arguing that a bus driver who stole Goya portrait from the National Gallery hadn’t “stolen” the painting but had planned to give it back after a ransom was paid to charity.

Hutchinson was junior counsel for his best-known case, when he defended Penguin Books against obscenity charges in 1960 for publishing an uncensored version of DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Originally released in Italy in 1928, the book featured detailed sex scenes and used expletives liberally.

(As the prosecution put it: ”The word ‘f***’ or ‘f***ing’ appears no less than 30 times ... ‘C***’ 14 times; ‘balls’ 13 times; ‘s***’ and ‘arse’ six times apiece; ‘cock’ four times; ‘piss’ three times, and so on.”)

Hutchinson – in an echo of his father, a lawyer who had rescued some of Lawrence’s sexually explicit paintings during an obscenity case in the 1920s – sought to make a similar case for Lady Chatterley’s literary merit.

He called on witnesses such as EM Forster and pressed for the inclusion of female jurors. “I found that women were far more sensible,” he said later, “and had very much less baggage than men on matters of sex.”

Lord Hutchinson seemed to be proved right when prosecutor Mervyn Griffith-Jones asked the jury, “Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?” Several jurors burst out laughing, and after rendering a verdict of not guilty, Lady Chatterley’s Lover sold 200,000 copies on its first day of publication.

He successfully defended works including the scholarly book The Mouth and Oral Sex (1969). He ridiculed the presiding judge who asked a defence witness why a study of the sex act was necessary, given that “we have managed to get on for a couple of thousand years without it.”

In his closing speech to the jury, Hutchinson quipped, “Poor His Lordship! Poor, poor His Lordship! Gone without oral sex for one thousand years.”

Hutchinson’s legal battles against censorship continued, most memorably with his defence of Howard Brenton’s play The Romans in Britain, which premiered at the National Theatre in 1980.

Mary Whitehouse, the late outspoken defender of conservative values, charged the play’s director with procuring “an act of gross indecency” during a scene that portrayed a Roman soldier’s anal rape of a Celt. The key witness claimed to have seen a flash of an erect penis on the stage.

In court, Hutchinson proceeded to demonstrate that the witness was sitting a full 90 yards from the actors. Tucking his hands under his gown and wiggling a thumb inside his fist, he argued that the witness might easily have mistaken one fleshy protuberance for another.

The courtroom descended into laughter, and the charges were soon dropped.

Hutchinson studied at Oxford before beginning his legal career in 1939. He served in the navy in the Second World War, surviving a bombing run that sank his vessel during the Battle of Crete. Floating in the water for hours before rescue, he sang to maintain morale and clung to wreckage alongside the ship’s commander, Louis Mountbatten.

Hutchinson’s marriage to Ashcroft ended in divorce. His wife of 40 years, the former June Osborn, died in 2006. Survivors include a son from his first marriage, Nicholas Hutchinson, and several grandchildren.

In 2011, Hutchinson took the unusual step of retiring from the House of Lords. He spent the past several decades focused mainly on art, serving as a trustee and chairman for the Tate and helping establish Tate Liverpool.

In recent years, he lamented changes in the legal system, particularly funding cuts to legal aid. “The result,” he told BBC Radio 4, shortly after celebrating his 100th birthday, “is the criminal bar will only serve people who have enough money to pay for it.”

Jeremy Nicolas Hutchinson, born 28 March 1915, died 13 November 2017

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks