Lord Glenconner: Owner of the island of Mustique whose friendship with Princess Margaret kept him in the public eye

Colin Tennant, the third Baron Glenconner, had a permanent place in the gossip columns for most of the second half of the 20th century, largely because of his intimate friendship with Princess Margaret; but also because of his Faustian compact with fame – or, perhaps, notoriety. Throughout the 1980s in particular it seemed as though Nigel Dempster had a hot line to Glenconner's bedside phone. Given to extravagant gestures – for his 60th birthday party in 1986, the likes of Jerry Hall, Raquel Welch and Princess Margaret flew to Mustique at his expense for a Peacock Ball – he was seldom out of the limelight. And yet for all these fitful wonders he was an essentially honest and charming man in whose company one was often reduced to helpless laughter.

Lord Glenconner's background provided ample genetic precedence for his eccentricities. His paternal grandmother, Pamela, Lady Glenconner, was one of the aristocratic-bohemian Souls of the Edwardian era who conducted life at her Arts and Crafts manor near Salisbury, as a kind of Rousseauesque charade. Peter Quennell recalled that Lady Glenconner would greet visitors arranged in an 18th-century tableaux – a sense of fantasy inculcated in her son, Stephen Tennant, whose sayings as a child she published, and who would live out a decorative reclusion at Wilsford surrounded by tropical lizards, polar bear skins and the rainbow glitter of his imagination. It was to Wilsford that his nephew Colin brought Princess Margaret for an audience with his eremitic uncle, only to be told by Stephen's butler that his master was seeing only blond-haired visitors.

Although he preferred the exploits of his maternal grandmother, Lady Muriel Paget, who during the Russian Revolution had had guns pointed at her, only to reply "Nonsense!" and push them away, Glenconner would maintain more than a little of the Tennants' mercurial, sometimes frustrating feyness in the character he created for himself. Modern eyes would be opened to his more colourful aspects in The Man Who Bought Mustique, a film directed by Joseph Bullman in 2000, which followed Glenconner as he prepared for a visit by Princess Margaret to his island. The vision of Glenconner barking imperious and impetuous commands to his hapless assistants encouraged reviewers to believe he represented an egregious example of feudal arrogance, if not near-lunacy.

A few months after the film aired, I was sent on assignment to interview Glenconner for an article commissioned by Tina Brown for her magazine, Talk. He had agreed to talk about his relationship with Princess Margaret, who was then seriously ill. As I had written a biography of his uncle Stephen, Glenconner told Brown he wanted me to conduct the interview.

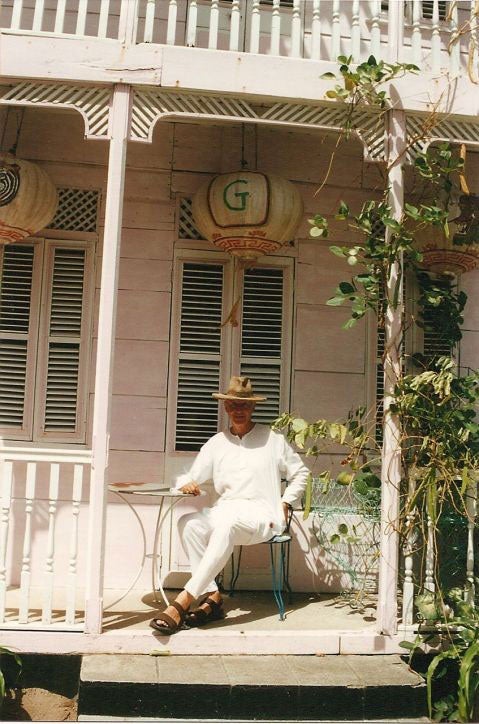

Having recently watched Bullman's film, I almost turned down the offer. I recall arriving in St Lucia, the island to which Glenconner had retreated after his Mustique dream had ended in acrimony, with some trepidation. In fact, as his faithful driver and loyal factotum, Kent, delivered me to what looked like a beach hut perched in the most desirable position on the island the man who greeted me was charm itself. Tall, thin, clad in white shalwar kameez, a battered straw hat and all-terrain sandals, Lord Glenconner resembled a character out of Evelyn Waugh via Hello! He bid me sit down, and we talked – for the next five days. Intelligent, well-read, with impeccable manners, he was one of the most entertaining men I have met; I saw that he had inherited his uncle's winning, but perhaps dangerous, allure.

Colin's father, Christopher, was the second eldest son of Eddy and Pamela Glenconner. Their eldest son, Edward "Bim" Tennant, a budding poet, died during the First World War, leaving Christopher to inherit the title on his father's death in 1922, as well as the baronial pile, Glen, in Perthshire, and responsibility for the family business (the Tennants' wealth dated back to the Industrial Revolution and the discovery of a chemical formulation for bleach). Colin was born in 1926, and educated at Eton. In 1945 he served in the Irish Guards as a second lieutenant, joining because his aunt Clare had introduced him to the colonel-in-chief, who had greeted Colin from his bed, and "enlisted" him then and there.

In 1949 he went up to New College, Oxford then joined the family firm, but his father doubted his aptitude for the business, and in 1963 sold it before retiring to Corfu – even though his sonwould claim, "I was, frankly, running the company brilliantly". His kinsman, Simon Blow – whose Broken Blood: The Rise and Fall of the Tennant Family would receive its controversial publication in 1987 – maintained he was "hardly ever" in the office, preferring to concentrate on his social life and driving his Ford Thunderbird.

According to Blow, the genetically frail nervous disposition of the Tennants resurfaced in its scion: shortly after the sale, Glenconner suffered a breakdown. While driving to Scotland, he felt himself "dissolving into gold dust", and a car had to be sent to collect him, Blow recorded (although he in turn would be accused by Colin's half-sister, the novelist Emma Tennant, of fancifying his family's history).

Glenconner left for the Caribbean. There the family had owned an estate in Trinidad which he had sold for £44,500 in 1958, and shortly after had bought Mustique for £45,000. Named after its giant mosquitoes, the island was three and a half miles long, and Glenconner set about developing it as a deluxe resort. It was an age when English aristocracy was diversifying to survive; and where the Baths of Longleat had their lions, Glenconner had his commodified paradise. The key to success was to attract the right people, and he knew them – pre-eminently in the shape of Princess Margaret.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s the Princess had ruled over "the Margaret Set", a new kind of royal for a post-war world, the Brideshead generation updated to an era of coffee bars and Teddy boys. Glenconner fell easily into her circle: he was rich, good-looking and witty; an elegant dandy who once had a suit made without any pockets.

Margaret was also in the throes of her desire to marry a commoner, Peter Townsend, and Glenconner was a useful diversion. The pair were seen together constantly: he claimed to have been the first to take her out shopping by walking along Bond Street.

Speculation about their relationship seems part of the smokescreen. It was noted that the pair stayed at Glen, and were together at Balmoral for her birthday: Glenconner dreaded coming down to the newspapers at breakfast, with "announcements" of their engagement. Later he said that the Princess intimated to him that he had "as good as" proposed to her; he thought this might have been true, but couldn't have imagined life with her: "She would have been an impossible wife."

After Margaret's marriage to Lord Snowdon on 6 May 1960, the couple honeymooned in the Caribbean; Glenconner made them a wedding present of 10 acres of land on Mustique. It was Snowdon's first and last visit to the island, and Tennant saw little of Margaret until her marriage began to disintegrate. In 1967, seeking refuge from the media and her own royal duties, she asked Glenconner if he had been serious about his wedding present.

"I said, 'yes', and she said, 'Does it include a house?' I said, 'Yes'. I couldn't really say anything else, could I?" Les Jolies Eaux, a 10-bedroom, pale-green painted villa, turned out rather more costly than Glenconner had envisaged, at £25,000. But he had his jewel in the Princess's royal presence. She went out twice a year, in February and late autumn, presiding over a social set which sometimes lurched into loucheness, with characters such as the East End-criminal-turned-actor John Bindon. However, Glenconner denied that Bindon had produced his prodigious manhood for royal eyes; the flashing was done to one of her ladies-in-waiting, who merely commented, "I've seen bigger".

In 1971, Glenconner's wife Anne, the eldest daughter of the fifth earl of Leicester, whom he had married in 1956, became the Princess's lady-in-waiting. She put them up in Kensington Palace when they were "homeless"; and, when they found a house, helped them move in. Yet Glenconner would complain of her social tyranny, saying, "she hasn't got any real friends".

He was ever a man outside his own society. Tennant had given up on life in England, later putting his 19th-century mansion Hill Lodge on the market for £6m. Glen and its 9,000 acre estate, which his father Christopher had made over to him in 1963, and which he had used fitfully in the 1960s and 1970s, had lost its sense of being a family home and would later be run as a business. With his edgy exile from Mustique after a row over electric prices in 1977 he sold his Great House there for £2m and moved 45 miles north to St Lucia, where, he claimed, he was for years "the only white man".

In 1981 he bought the 480-acre Jalousie estate. A former sugar plantation, it had been found by his son Henry. Set on the bay between the Pitons, it was a great chunk of Eden, sloping down to the palm-fringed beach and back up into hills lush with avocado trees. Glenconner installed two early 20th-century gingerbread cottages salvaged from elsewhere on the island, joining them together and furnishing them with an eclectic mixture of family heirlooms and Indian antiques. Next door he established his fantastical beachside restaurant, Bang, (as in "bang between the Pitons"), based on Messel's stage designs for the 1950s Broadway musical House of Flowers.

But the 1980s brought reversals of fortune. With his father's death in 1983 he became third Baron yet he felt obliged to disinherit his eldest son Charlie, a heroin addict, in favour of Henry – only for Henry, who was gay, to contract HIV, as did Charlie. Then in 1987 his youngest son Christopher was left partly paralysed by motorbike accident in Belize. Henry, a colourful figure 6ft 7in tall with long blond hair, died of an Aids-related illness aged 29 in 1990. Six years later Charles died, aged 39. These tragedies were invoked as "the Tennants' Curse".

Tennant's attempt to run two-thirds of the Jalousie estate as a four-star resort failed after three seasons. In 1995 he sold the resort to the Hilton chain, much to the displeasure of environmentalists and Prince Philip, who twice wrote to St Lucia's prime minister asking for the scheme to be halted. Other parcels of land on what he now branded the Beau Estate were sold. Margaret would visit, staying in a hillside villa Glenconner found for her. In March 1999 she was staying at the Jalousie Hilton when she scalded her feet in a boiling shower, an accident which seemed to precipitate her decline.

Her death, in 2001, did not seem to affect him greatly. He seemed more saddened by the memory of Bupa, his Indian elephant brought as an attraction for his restaurant. The day it arrived, Winston Kent Albert, a local, jumped on its back – and became the elephant's carer and Glenconner's right-hand man. Bupa died in 1994 after being fed dry buns which swelled in its stomach. "One of the great tragedies of my life," Colin said as he showed me her tusks. "It changed my life completely."

Bang was popular with the passing cruise liner trade, although Glenconner would complain that no one interesting came, Yet he made a point of knowing their names, greeting every customer at the entrance to its surreal courtyard. "No one says anything interesting or witty anymore," he complained. "No one lurches in drunk."

He maintained an interest in politics and still referred to himself as a Liberal peer. He was interested in modern art and literature, and could drop into conversation that his grandson's godfather was Guy Ritchie. But his eyes only really lit up when describing one of his Indian jewels, or showing a guest the fabulous new folly he was building.

The point about Glenconner was not his eccentricity; they were just as much projected images as the performing host at Bang. The real heart of the man was his boyish charm and his ability to envelope you in his world. Like his uncle Stephen, he never seemed to have grown up – or, at least, accepted the banalities of modern existence.

Colin Christopher Paget Tennant (Lord Glenconner), landowner: born 1 December 1926; married 1956 Lady Anne Coke (one son, one daughter, and two sons deceased); died St Lucia 27 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks