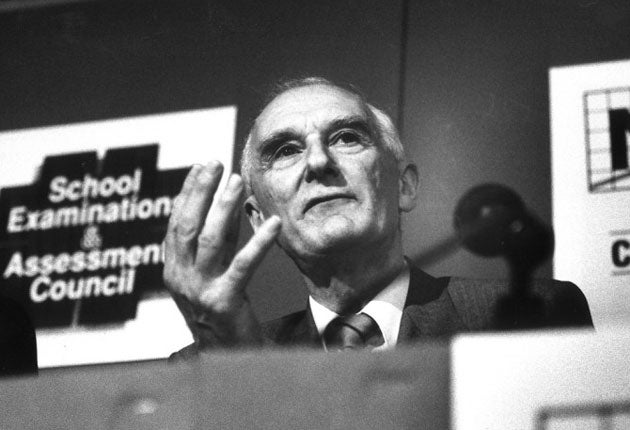

Lord Dearing: Civil servant whose 1997 report paved the way for the introduction of university tuition fees

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lord Dearing, who has died aged 78, helped shape Britain's education system, functioning not as a politician or civil servant but as a deus ex machina, summoned by ministers to extricate them from thorny political thickets.

In report after report he set out the arguments and delivered recommendations which were generally accepted. Repeatedly called upon for guidance by governments, he was described as "the almost perfect public servant." He was no dull uninteresting bureaucrat. He could conjure consensus from impasse. He was a non-political figure who deeply impressed politicians ranging from Tony Benn to Keith Joseph and he had legendary listening skills.

He was both a safe pair of hands and a man who could advocate radical departures, a supreme educationalist who had himself left school at an early age. The judgement of the one-time Labour minister Gerald Kaufman was that he was "brilliant, inventive, humorous, loyal and prolific."

In fact the keenly exacting Kaufman went further, conjuring up an image of a razor-sharp yet properly deferential Dearing obliging perplexed ministers in the manner of the Admirable Crichton, or indeed of Jeeves, shimmering in to deliver deft solutions to obstinate problems. Dearing memos, as convincing as they were comprehensive, would be so persuasive, according to Kaufman, that they left him with little else to do apart from note: "I agree with Mr Dearing."

Both Labour and the Tories recognised his skills as invaluable, assigning him to bring organisation and order to institutions such as the education system and the Post Office, and appointing him to innumerable other positions. He was a unique mixture of workaholic and expert problem solver. He once said: "Whenever I sit down at my desk and open a file, I think – aren't I lucky to be allowed to open this file?"

Ron Dearing, born in Hull, lost his father when he was 10. A clerk who was acting as fire-watcher, he was killed by a bomb during a Second World War air raid on the local docks. While Dearing's mother went out to work he lodged with a succession of families. The stay which most influenced him was with two Yorkshire brothers who imbued him with both the Methodist religion and its work ethic.

He left Doncaster grammar school at 16, going to work in a labour exchange. The years that followed brought National Service in the RAF, an economics degree from Hull university and a year at the London Business School. Within the civil service they also brought him experience in the Ministry of Labour, Ministry of Power, the Department of Industry and the Treasury. Along the way he married, having met his wife Margaret in a Methodist community in London.

By the late 1970s he had established himself as a figure of great judgement and common sense within the civil service, respected by both left and right. He never voted. He once said: "I am not political and have never been aligned to any party, but I have worked with ministers from Keith Joseph to Tony Benn without difficulty."

As the one-time Tory education secretary Lord Baker remembered him: "He was a tremendous diplomat, a great believer in distancing himself from any political commitment so that he could give his judgement unsullied to any minister from any party."

It was during the Thatcher years that he was snatched from the ranks of bureaucracy and pushed into the managerial front line as chairman of the Post Office.

"I'd never even run a coffee shop," he recalled wonderingly," and here I was being offered a business. So I put on my hat and coat and went." His six years at the helm were widely viewed as successful in turning it into a profitable concern before he stepped down in 1987.

After the Post Office came a blizzard of jobs and roles in business and public life: he was a director of the Prudential, Whitbread and British Coal, among many others. He had connections with many universities, attracting a multitude of academic honours.

It came as a surprise in 1997 when he served for two years as chairman of Camelot, which was awarded the franchise to run the National Lottery. It seemed incongruous, and did not chime with anything else on the Dearing CV. But he was convinced the enterprise would not encourage a serious gambling habit. "You pick numbers and it's luck," he rationalised. "It's not going to be the sort of thing that causes people to invest large sums of money."

It was in education that he left a lasting mark, most notably by producing the mammoth 1997 treatise, known as the Dearing Report, which paved the way for the introduction of tuition fees for students. This was controversial – for some it still is – but it had the merit of introducing some semblance of order in place of the previous chaos.

For once the Labour government did not say, as Gerald Kaufman used to, "I agree with Mr Dearing," and did not adopt his recommendations in full. He felt particularly strongly about making access as wide as possible.

"After all," he once said, "I was one of those who had to batter at the door to get into higher education. I found it very difficult to get through the door because I didn't have any money." The former education secretary David Blunkett said of Dearing's own educational path: "I think it was a driving force – to have actually seen that education was the ladder out of poverty."

His role in introducing fees, a fundamental departure, was his most striking contribution to education, but by no means his only one. As a civil servant, Kaufman had said, Dearing was probably "the most prolific there has ever been," and as an education consultant he proved equally productive. He produced reports on church schools, on reforming and streamlining the school curriculum, and on the teaching of foreign languages, to which he attached much importance.

As a member of the House of Lords he spoke not just on the issues he was primarily associated with but also on topics as diverse as Northern Rock, prison rehabilitation and climate change.

His years of mixing with the great and the good, the powerful and the wealthy, did not affect his basic modesty. Lord Baker recalled: "He'd often like to travel not first class but standard because he would like to talk to people during the train journey. When it came to the stage of having a chauffeur and a car, he used to drive the chauffeur home himself and pick him up again in the morning."

He left behind at least two characteristic sayings. On taking on one knotty task he said: "There will be problems, of course, but they will be solved." On another occasion he summed himself up: "People know that I like taking things on. I'm not so modest that I think I can't do things. And I suppose so far I haven't had too bad a record."

David Greenaway, vice-chancellor of the University of Nottingham, said in a tribute: "It was a real privilege to work with him. I know that is a bit of a cliché, but I genuinely mean it. He was a great man."

David McKittrick

Ronald Dearing, civil servant: born Hull 27 July 1930; Ministry of Labour and National Service, 1946–49; Ministry of Power, 1949–62; HM Treasury, 1962–64; Ministry of Power, Ministry of Technology, Department of Trade and Industry, 1965–72; Under-Secretary, DTI, later Department of Industry, 1972–76; Chairman, Post Office 1981–87; Chairman, Camelot Group, 1993–95; Chairman, National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education, 1996–97; Chancellor, Nottingham University, 1993–2001; created Baron Dearing of Kingston upon Hull, 1998; Chairman, Committee of Inquiry into Church Schools 2000-01; married 1954 Margaret Riley (two daughters): died 19 February 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments