Lewis Gilbert: Bond director behind era-defining British films Alfie, Shirley Valentine and Educating Rita

Gilbert made stars of Michael Caine and Julie Walters, and directed three of the most extravagant films in the James Bond series

The scene should have been simple enough: Michael Caine stands alone on Waterloo Bridge; a stray dog approaches him, they look at each other, he smiles; he calls to it and together they walk away.

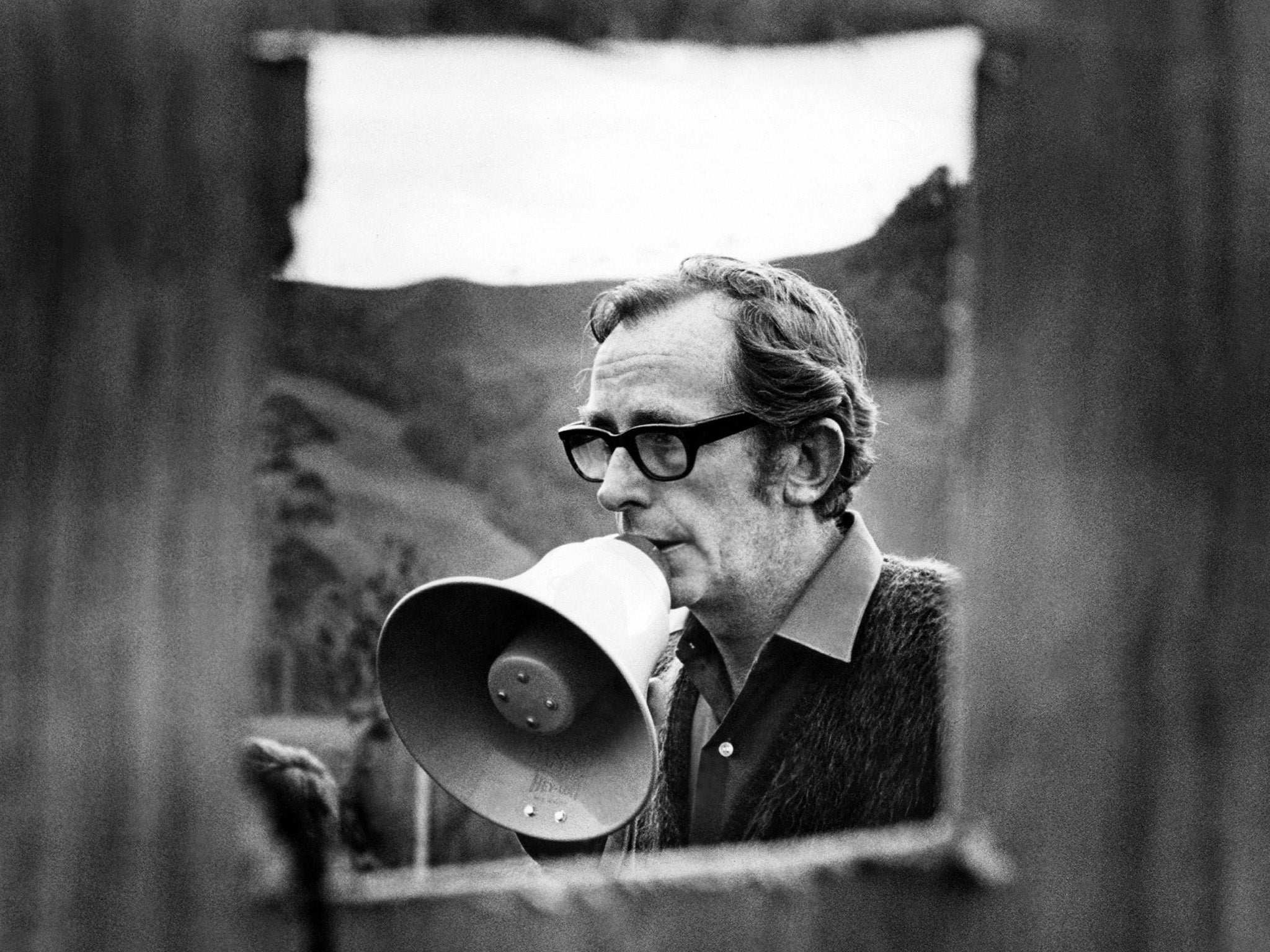

But on this rainy night in 1965, the film crew spent hours shooting the final scene in Alfie. Up on a crane feeling wet, cold and miserable, was Lewis Gilbert, the director. At six in the morning, he finally got the shot he needed, and could let the traffic through. Allowed to cross the bridge at long last, an irritated lorry driver called out to Gilbert: "Why don't you get yourself a proper job?" That brought a smile to his face.

Entertainment was the only job Gilbert ever knew. From his beginnings as a child performer on his parents’ touring vaudeville act to his directorial successes with three James Bond films and with Educating Rita (1983), Shirley Valentine (1989) and Alfie (1966), Gilbert, who has died aged 97, never erred from show business. “I never knew anything else from birth,” he said late in his life.

Lewis Gilbert was born in Hackney, east London, in 1920, the second child of dancers Ada Gilbert, née Griver, who was of Jewish Russian descent, and George Gilbert, who was of Irish Catholic extraction.

Gilbert grew up touring with his family, and attending school only intermittently. Every night he stood in the wings, watching, as his parents’ act unfolded. The line between reality and fantasy is blurred for all children, but that was all the more true of little Gilbert, whose early life was spent in the company of dancers, ventriloquists and actors dressed as fantastical creatures.

His stage debut came at the age of four, when he pedalled on to the stage on a tiny bike where a trick cyclist had just exited, making it look as if the cyclist and his bike had shrunk. The house erupted.

But George died soon thereafter, of tuberculosis, and much changed after that. Many nights Gilbert cried himself to sleep, and what remained of the family found itself destitute. To make ends meet, Ada started working as a film extra. Gilbert followed suit, appearing first in silent films then in the earliest talkies. Soon he was the family’s primary breadwinner.

Gilbert spent countless hours with crewmembers, from whom he learned “how you can make film dance along and tell a story”, as he later wrote in his autobiography, All My Flashbacks.

To do just that, he gave up acting and became an assistant director instead. On sets in the lead-up to the Second World War, he worked alongside such giants as Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh, Graham Greene and Alfred Hitchcock.

At the outbreak of the war, Gilbert volunteered for the Royal Air Force. But suffering from poor eyesight, and with no mechanical skills, it soon became apparent that he would be of little use. To his relief, Gilbert found a way back to what he loved: he became an assistant to Colonel William Keighley, who was shooting war propaganda for the US army. Gilbert shot his first scenes, and met Hollywood greats Frank Capra, Clark Gable and Jimmy Stewart when they came to visit Keighley’s office, in London.

But another encounter was to make an even greater impression on the young Gilbert. Towards the end of the war, he pressed the button for the lift at a London studio. When the doors opened he was faced with Hylda Tafler, an actress and model wearing, for a part, an 18th century dress. Gilbert was awestruck by her beauty and soon they were dating. Hylda had been married before, and had a four-year old son named John. Gilbert was moved, remembering how his mother had brought him up largely on her own, and they became close.

After the war, Gilbert directed his first feature film, The Little Ballerina. Still, he was wrought with self-doubt and, fearing he might not be able to support Hylda and John, he broke up with her – a decision which he soon bitterly regretted. They would eventually reunite, but not till after Hylda had married, and divorced, once again.

Gilbert found success directing war films in the 1950s and early 1960s. But it was a chance meeting by Hylda that would make him a much sought-after director. At a London hairdresser, she sat next to an actress who was in a play she was sure would make a good film. Hylda was soon convinced, and in turn she convinced Gilbert, who recognised in the story “a new kind of hero” who could typify 1960s London. The play was Alfie, by Bill Naughton.

To play the lead role of Alfie, a modern-day Don Giovanni who serially seduces then discards women, Gilbert thought a man with “an effortless cockney” was essential. He cast a young Michael Caine. When he told Paramount whom he had chosen, the studio replied, “Michael who?”

But the project was cheap enough that a potential flop mattered little to funders, and Gilbert was given free reigns to direct and produce it as he saw fit. The finished product was strikingly new: the film’s working class protagonists, carefree jazz soundtrack, heart-wrenching home abortion scene, and, most of all, its lead actor – a supremely charismatic Caine, who spoke directly to the camera – made it a huge international hit, if a controversial one.

Soon after Alfie was released, the producer Albert Broccoli rang to ask Gilbert whether he would direct the next instalment in the James Bond series. “You have the world’s biggest audience and it’s waiting to see what kind of a hash you make of it,” Broccoli half-jokingly told a hesitant Gilbert. That swayed him.

Gilbert went on to direct three Bonds: You Only Live Twice, starring Sean Connery, and, with Roger Moore, The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker. These films are some of the most extravagant in the series, featuring as they do a ninja army, a villain’s lair hidden within a volcano, an amphibious car, a laser battle in space, and the toothy henchman Jaws.

In the 1980s, Gilbert directed Educating Rita, which introduced Julie Walters to a wide audience, and Shirley Valentine – both films about brave and funny women trying to find themselves by stepping outside their harsh social conditions.

Gilbert did not hesitate to speak his mind. He found Laurence Olivier “a bit hammy”, said Ian Fleming’s You Only Live Twice had no plot to speak of, “merely a series of incidents”, and called The Adventurers, another big-budget film he directed, “a bullshit story”.

Directing The Adventurers was the lowest point in his career, he said, as Hollywood executives used a contract he had signed to force him to make that film over Oliver!, the musical which he had long dreamt of adapting for the screen.

Still, such disappointments did not make him any less committed to his line of work. “Films have been my life,” he wrote. “All my waking hours and sometimes my sleeping ones too, the making of them has obsessed me.”

So varied is his filmography of nearly 40 films over six decades that it can seem to lack any kind of unity. But he tended to gravitate towards stories of adventure and self-discovery, and most of his work is infused with an unmistakable Britishness.

Gilbert’s favourite dish, fish and chips, was quintessentially British, too. But he also had a taste for Gallic cuisine, and spent much of his later life in the French capital of film, Cannes. His other great passion was football, and he was a lifelong supporter of Arsenal.

By insisting on casting Michael Caine and Julie Walters in his films, Gilbert did much to introduce working class voices, carrying working class stories, into the mainstream. That may be his most significant contribution to postwar British cinema.

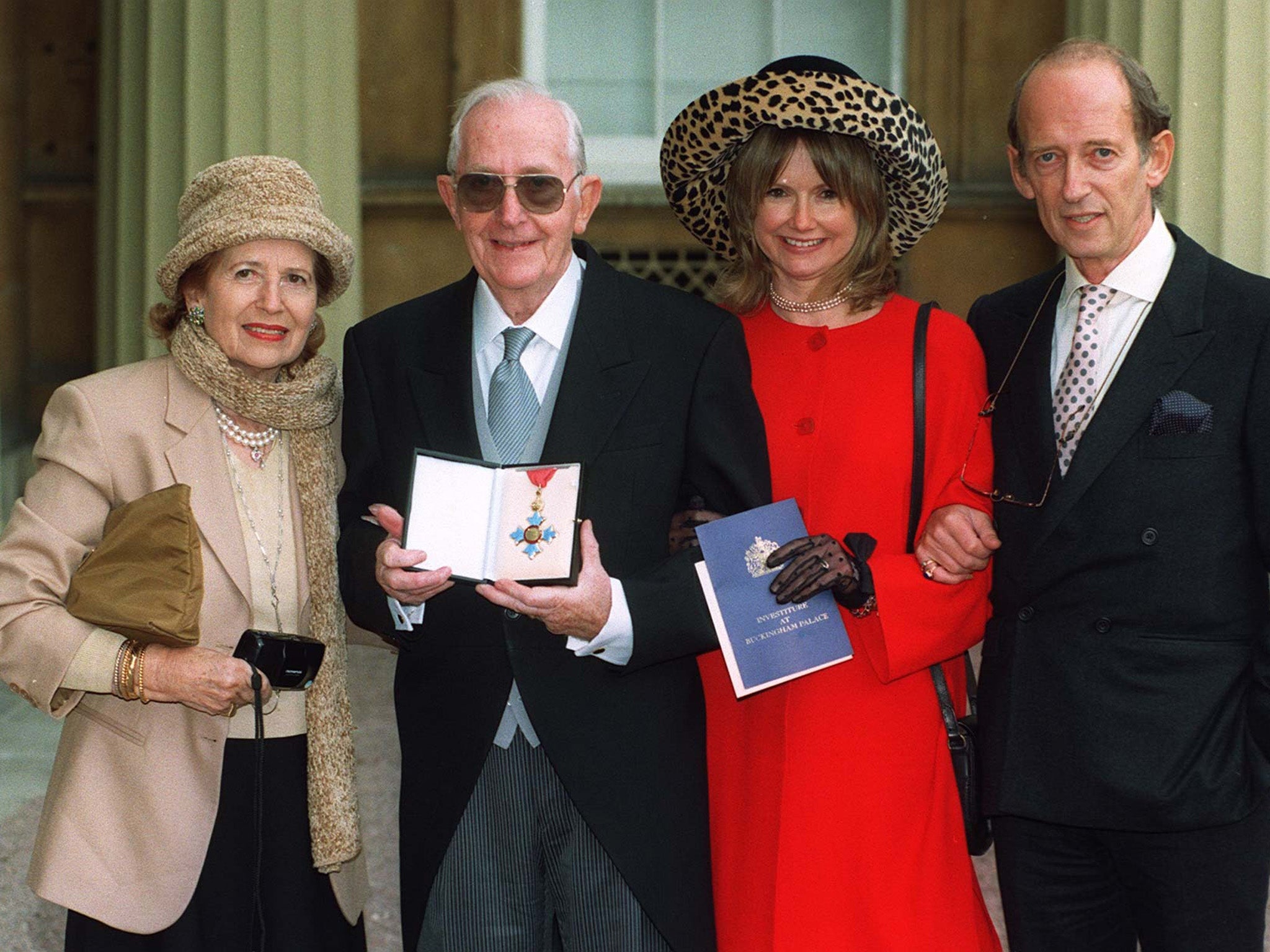

He is survived by John, whom he adopted, and by Stephen, whom he had with Hylda. She died in 2005.

In 1932, Gilbert, then a child actor, was asked by The Evening Star what he wanted to do when he grew up. He answered: “I want to be working in films when I’m 80.” He shot his final one at the age of 82.

Lewis Gilbert, British film director, producer and screenwriter, born 6 March 1920, died 23 February 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks