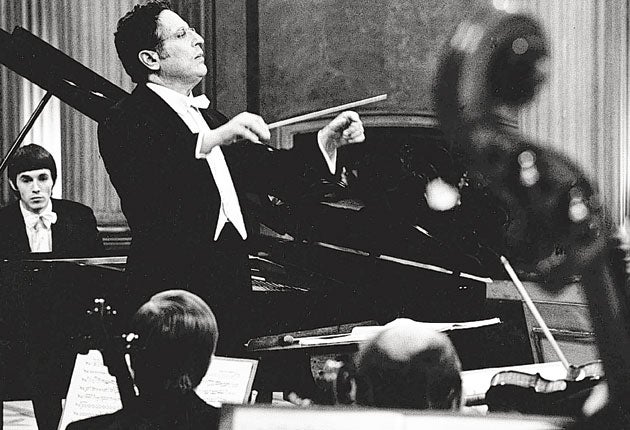

Kurt Sanderling: Conductor widely regarded as one of the greatest of the 20th century

Kurt Sanderling was one of the greatconductors of the 20th century, a last living link with the era ofthe podium giants, a man whose personal modesty was matched by immense musical authority. You came away from a Sanderling concert having had music you thought you knew revealed in its true nature, it seemed, for the first time.

Sanderling's career reflected the turbulent path of the century itself. He was born to a Jewish family in Arys in East Prussia (now Ozysz in Poland) and took piano lessons as part of a private education. For his further studies he moved the short distance north to Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) and then to Berlin. That city was to become the focus of his life for the next few years when in 1931, a mere 18 years of age, he secured a post of répétiteur and assistant conductor at the Städtische Oper in Charlottenburg. Otto Klemperer, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Erich Kleiber and Bruno Walter were all conducting in Berlin at the time, and Sanderling later reported that he learned a lot by watching them.

But within two years the Nazis came to power, and like hundreds of other Jewish musicians, Sanderling's world was turned upside down. To keep Jewish and "Aryan" musicians apart, the Nazis founded the Jewish Cultural Association which, in the main German cities, allowed the Jews to maintain the music-making and other activities they had enjoyed, and Sanderling was briefly active in the Jüdischer Kulturbund in Berlin.

Deprived of his citizenship in 1935, Sanderling found himself unable to return to Germany after an Italian holiday and so had to decide where he might settle. Though most German Jews who could escape went west (like his close friend, the conductor and composer Berthold Goldschmidt, who came to London), an invitation to join the staff of the Metropolitan Opera in New York proved worthless since he couldn't obtain the affidavit on which the US authorities insisted. He therefore was forced to look east, and an uncle, an architect-engineer working in Moscow on a contract, was able to get him permission to move there.

Sanderling soon made his mark, in a debut concert with the Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra in 1936, remaining at its helm until 1941; concurrently (1939–42) he was the chief conductor of the orchestra in Kharkov (now Kharkiv) in the Ukraine, which is where he first conducted Shostakovich, giving the second-ever performance of the Sixth Symphony.

It was his next appointment that made Sanderling's name, and provided the basis of a long and fruitful friendship with the composer: in 1941 he was named "Permanent Conductor" of the Leningrad Philharmonic, alongside its chief, Yevgeny Mravinsky. For almost two decades these two very different men – Mravinsky the disciplinarian and Sanderling more of a colleague, though no less exacting musically – together made the ensemble a byword for precision and polish.

Shostakovich's music became one of the mainstays of Sanderling's repertoire, particularly the Symphonies Nos. 5, 6, 8 and 15. "I was always more impressed by the 'poetic' Shostakovich than by the epic one," he explain-ed. Shostakovich counted Sanderling, alongside Mravinsky, David Oistrakh, Mstislav Rostropovich and Galina Vishnevskaya, as one of the five music-ians "who have accompanied my life".

By now a Soviet citizen, Sanderling was allowed to return to his homeland only in 1960, as the chief conductor of the Berlin Symphony Orchestra in East Berlin, and he had a similar galvanising effect on playing standards in the 17 years he spent there. From 1964 to 1967 he was also chief conductor of the Dresden Staatskapelle. He turned down proposed appointments at the Berliner Staatsoper.

His long connection with Britain began in 1970, when he appeared in London with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. A close link with the Philharmonia Orchestra was born in 1972, when he stood in for an ailing Otto Klemperer, with one of Klemperer's landmark works, Beethoven's Eroica Symphony, in the second half of the concert. The association lasted for almost three decades: Sanderling's final engagement with the Philharmonia, for a searing performance of Shostakovich's Fifteenth Symphony, came in September 2000; he had been named Conductor Emeritus in 1995.

As David Whelton, the General Manager of the Philharmonia reports, "for the Orchestra to be conducted from the score that had the composer's own markings was an unforgettable experience". The players, for their part, "never tired of his distinctive brand of acerbic humour". Sanderling was generally an apolitical man (he once observed wryly that "Others made history; I made music"), but on one occasion, when he wanted more vehemence in the Scherzo of Shostakovich's Fifth Symphony, he shouted to the Orchestra: "Politicians – yuck!"

Sanderling's musical sympathies ran much wider than Shostakovich, of course, and he was a discerning interpreter of the Viennese classics, recording all the Beethoven Symphonies with the Philharmonia; his Brahms, Mahler and Sibelius were similarly superb. Sanderling was also a prized presence in Japan, where he conducted the Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra from 1979, working also in the US, Australia and across mainland Europe.

Wherever he conducted, his musicians responded with respectful admiration to his detailed demands in rehearsal: he knew the sound he wanted and would work patiently with the players until it was obtained. In the early 1970s Douglas Cooksey, working for the BBC, sat in on a Sanderling rehearsal of the Schubert Eighth and Ninth Symphonies with the Scottish National Orchestra in Glasgow where he "made very clear his displeasure with the slightly raucous trombone section in the Unfinished, at one point saying, 'Never, never that sound in Schubert', and he also worked really hard on that rising string phrase at the end of the piece, shaping it like a kind of musical question mark". Another major concern was what Sanderling called "agogic balance": the correct structural relationship of the tempi in an extended piece of music. It was one of the main elements in giving his performances such terrific concentrated power and vivacity.

Sanderling's sons – Thomas by his first marriage, and Stefan and Michael from the second – have all become conductors, though not at his behest. "He did not encourage us to take to that complicated profession," Thomas recalls, "because he knew that a young person can initially see only the 'shiny' part which is more obvious and not the deep, complicated side of it, which was for him the important one."

After seven decades of giving concerts, Kurt Sanderling gradually began to wind down his activities, limiting his concerts to cities with direct flights from Berlin, and then to Berlin itself. He finally announced his complete retirement on his 95th birthday: he remained entirely lucid but was no longer sure he could deliver performances that met his own standards. In any event, he told his son Thomas, conducting was a profession, not an obsession, and he wasn't dependent on it. He accepted public recognition – a CBE, and the Shostakovitch Prize of the Gohrisch Festival in 2002, for example – without false modesty but setting little store on acclaim. He died two days short of his 99th birthday, in the bosom of his family. Looking back on his life in an interview in a German paper, he stated: "I have done what was in my heart".

Kurt Sanderling, conductor: born Arys, East Prussia 19 September 1912; CBE 2002; married 1941 Nina Bobath (divorced 1960; one son), 1963 Barbara Wagner (two sons); died Berlin 17 September 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks