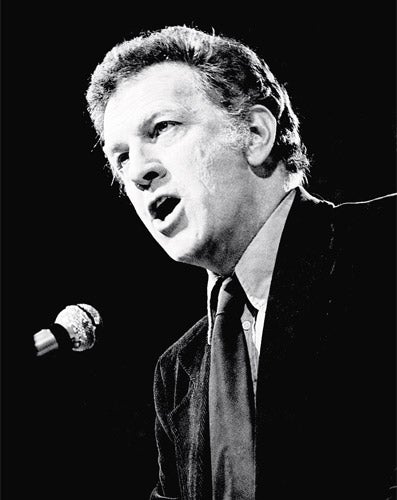

Ken Gill: Trade union leader who put the interests of his members before his communist politics

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ken Gill was a senior trade unionist and communist who, in his dealings with Labour and Conservative governments in the 1970s and 1980s, intriguingly did not fit into any of the familiar political or personal stereotypes. Although a hardliner, he generally avoided confrontation and strikes, was much respected for his inter-personal skills, and even displayed distinct artistic flair.

He was once described as Britain's most suave Stalinist. While he did not accept that label, he readily admitted to being a communist, continuing to use that description even after the party expelled him for clinging to the old-style Moscow line. Most other union bosses accepted his assertion that he always put trade union interests ahead of his personal politics. MI5 was sceptical enough about this, however, to put it to the test by bugging his phone and his home.

He was not usually to be found in the limelight: he tended to leave that to others such as Arthur Scargill. But though less conspicuous, he was perhaps one of the more individualistic members of what was dubbed the awkward squad. Born in Melksham, Wiltshire in 1927, the son of an ironmonger, he attended secondary school, refusing to take part in officer training because of his emerging political beliefs. He had a natural talent for drawing and sketching but his parents had, he said, "no sense of culture" and he concentrated on the technical rather than the artistic. He worked as a draughtsman, then after completing his apprenticeship was employed as a project engineer and sales engineer in a number of companies.

His introduction to left-wing theory had come during the Second World War when his family took in as a lodger a Welsh miner and communist who influenced Gill hugely. His earliest political involvement came at the end of the War when he acted as election agent for a local Labour candidate.

His long career in trade unionism, which began in 1962, took him through the Draughtsmen's and Allied Technicians Association and into its successor TASS, the Technical, Administrative and Supervisory Staffs Association. After various mergers he would end his career as head of MSF, the Manufacturing, Science and Finance union. He was also prominent for many years within the upper reaches of the Trades Union Congress.

Harold Wilson was baleful about Gill and other left-wingers whom he darkly referred to as "a tightly knit group of politically motivated men," by which he meant senior trade unionists opposed to Labour's income policy. Unions were still a formidable force in the land at a time when militancy was much more in vogue, and strikes and industrial action were commonplace. Unions hotly debated whether to support Labour policies or push for a more radical approach.

Many of them came down, often reluctantly, on the side of the government of the day, but Gill steadily opposed what he saw as Labour's attempts to reduce union power. He was well to the left of the bulk of his union membership, but he insisted that his stances were dictated by the interests of his membership rather than by the Kremlin.

At the same time he made no secret of his communist beliefs: he was certainly a red but did not lurk under the bed. After the 1968 Soviet intervention in Czechoslovakia, for example, he defended Moscow's action at a TUC conference. "I was barracked, stamped at, screamed at, ordered off the rostrum, and finally switched off," he recalled. "I left the dais to thunderous booing."

In one anecdote, however, he admitted being circumspect about his political beliefs. This, he recounted, was during a TUC trip to the US when he and others met four trade union leaders in Arizona. After an evening spent heatedly discussing the US citizen's right to carry arms, the four hosts admitted to owning 16 guns between them. On leaving, one of Gill's colleagues said to him: "Thank Christ you didn't admit to being a communist – they'd have killed the bloody lot of us."

But apart from that instance of tactical prudence Gill was open about his views. "My political position remains as it always did," he declared when he was elected chairman of the TUC in 1985. "I am a communist." He expanded on this: "I am a Marxist socialist, but I make independent judgments. As far as the union is concerned, never is it alleged that I depart from what is necessary to reflect the union's policy. Even my enemies would never accuse me of that."

Some on the far left, however, did accuse him of – very occasionally – being soft. Gill wrote that at one stage he agreed to drop a motion critical of Labour policy after a senior union leader "whispered to me encouragement, paternal advice and more than a little blackmail." Withdrawing the motion, he said, earned him a sneer from a young Arthur Scargill, who told him: "You'll end up in the House of Lords."

Gill was known as one of the union movement's internationalists, visiting many countries in the communist bloc and elsewhere. He was particularly supportive of the regime in Cuba, holding several meetings with Fidel Castro and, after retirement, chairing the Cuba Solidarity Campaign for 15 years. He was a keen supporter of Nelson Mandela for many years, his union supplying the hall used by Mandela to thank supporters on his first British visit.

Within the TUC he campaigned for greater priority for equality issues, calling on unions to appoint and elect black officers, monitor racial fairness and pursue immigration and asylum issues. In common with other union leaders, Gill found no effective way of countering Thatcherism. When he first met Margaret Thatcher he complained that "all we had from her was a primitive lecture on the evils of the trade union movement."

He was supportive of the mid-1980s miners' strike but although a hardliner he was no Arthur Scargill, harbouring no ambitions to engage in class warfare or to stage politically motivated confrontations. After the strike he and other union leaders were left to pick up the pieces and contemplate the remnants of their influence. He would later lament that "in 50 years of trade union activity I have seen the sense of power which is the hallmark of full employment gradually being replaced by uncertainty and division."

He was more flexible and pragmatic in union business than in matters communist. While the ranks of the Communist Party in Britain thinned out after the Soviet Union's actions in Hungary, Czechoslovakia and elsewhere, Gill stuck resolutely to the Moscow line. In the late 1980s a lilliputian dispute broke out within the communist party between traditionalists such as Gill and a new brand of updated "euro-communism." The Gill faction managed to hold on to control of the Morning Star newspaper, but he and others were expelled from the party. Accused of running "a semi-conspiratorial and undemocratic organisation with a self-appointed leadership," he was denounced for "opposing congress decisions, destroying the links between the party and the Morning Star and setting the comrades an example of arrogant disregard for party democracy." Years earlier MI5 had, according to a former officer and whistleblower Cathy Massiter, both tapped his phone and broken into his house to plant a bugging device: what, if anything, of interest it turned up remains unknown.

Despite his affinity with Moscow, Gill was no dour apparatchik, gaining a reputation as a witty and engaging individual who amassed fewer personal enemies than the average union leader. Colleagues from all over the political spectrum once voted him "the trade unionists' trade unionist." His old paper the Morning Star said in its obituary of him: "While he could be forceful and committed, he was rarely dogmatic or unnecessarily aggressive. His soft Wiltshire drawl and ready laughter belied his steely determination. His charm and persuasiveness easily disarmed many of his harshest critics. He was always popular and well-liked, even if his politics weren't."

Gill's personal style was reflected in the cartoons which he drew in their hundreds, often to relieve the tedium of interminable negotiations and meetings in smoke-filled rooms. Some of these were collected in a book published this year. It was said of his work: "He has a knack for capturing good likenesses and poked fun in a gentle fashion; they are rarely harsh or cruel." A professional cartoonist added: "They are affectionate rather than grotesque, but there's a confidence in the line which gives a brilliant insight into the confidence and determination of the man holding the pen."

Retiring in 1992, he did not fulfil Arthur Scargill's prophecy that he would end up in the House of Lords, though remaining on many issues such as opposition to the war in Iraq. He did not manage to have his chosen successor, an associate from the Morning Star, elected as his replacement. Nor did he manage to have what were regarded as generous retirement terms approved by his union: after complaints, which he characterised as a witch hunt, his benefits were reduced by one-third.

Tributes after his death were led by the TUC General Secretary Brendan Barber, who said: "Ken Gill was a big figure in the trade union movement during turbulent times. Always a champion of the left, he fought his corner with a steely integrity."

David McKittrick

Kenneth Gill, trade unionist: born Melksham, Wiltshire 30 August 1927; General Secretary, AUEW (TASS) 1974-86; Chairman, Morning Star, 1984–95; President, TUC, 1985–86; General Secretary, Manufacturing, Science, Finance, 1989–92 (Joint General Secretary, 1988–89); married 1953 Jacqueline Manley (divorced 1964), 1967 S.T. Paterson (divorced 1990, two sons, one daughter), 1997 Norma Bramley; died 23 May 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments