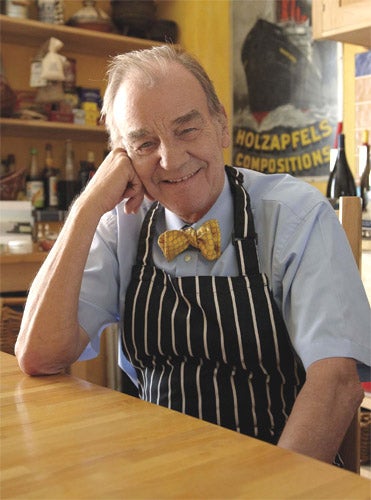

Keith Floyd: Television cook who paved the way for the modern generation of celebrity chefs

Keith Floyd was a television cook who enjoyed and profited from a large audience despite having no outstanding talent, either as a cook or as a TV presenter, no great knowledge of his subject, or any apparent passion for anything but drink. This is not to say that his first TV programmes were bad – they were, indeed, highly diverting entertainment, following in the 1969-71 footsteps of "The Galloping Gourmet," Graham Kerr (whose trademark glass of wine Floyd adopted). This, however, was not the result of any work by Floyd himself, or of a writer, but of his director, David Pritchard who, as is the way of these things, is not himself represented by an entry in Who's Who, though Floyd would not be there himself were it not for Pritchard's one big idea. Floyd always gave Pritchard, who now works with Rick Stein, the credit for "discovering" him, when the BBC Plymouth producer happened to be eating in Floyd's restaurant in Bristol, and asked him if he thought he could cook on camera.

The unique selling point of the show that resulted, Floyd on Fish, and of the remainder of their nine-year collaboration, was that, when Floyd, who had no script and no television experience, spoke directly to the long-suffering cameraman, "the famous Clive" North, and ordered him, for example, to "get a close-up" of whatever Floyd was preparing or cooking, Pritchard left in both the close-up and the banter with the cameraman. Pritchard also retained the footage of Floyd sipping the glass of red wine he was never without. In an interview with The Independent in 2007, he told Susie Rushton that the slugs of red wine afforded him a few seconds time to work out his next ad-lib, there being no script. This, fundamentally, was the basis of Floyd's successful run of 26 TV shows over 20 years. Floyd was hardly charismatic, but his conversational skills and ability to charm the viewer were, thanks to Pritchard, parlayed into a long career.

By the late '80s relations between Floyd and Pritchard had so soured that the pair only communicated by notes passed between them. Rushton said that "Pritchard wanted him to behave like 'a television freak' while the cook himself wanted to show his abilities," and the later programmes lack the spark of the earlier ones. She further asserts that, in their heyday the "Floyd On..." shows were must-watch television, their star the first bad-boy chef. His drinking, unabashed criticisms of bad food and the edited version of The Stranglers anthem "Peaches" that became his theme tune made for some of the sharpest TV around, and has continued to influence food programming to this day.

There are a lot of misapprehensions about Floyd's originality by writers too young to remember TV cookery shows before Floyd came on the scene in 1984. For example, "Floyd was a natural," according to Bill Knott, food writer and founder of the now-defunct magazine, Eat Soup. "His show was one of the first to take food out of the studio. He was a pioneer." Of course, Floyd – who was untrained, and never called himself a chef – did much of his cooking on precarious camp stoves in romantic and exotic locations. But to claim primacy for him is to forget Madhur Jaffrey's 1982 Indian cookery series for BBC2, much of it filmed on location, as was Ken Hom's 1984 Chinese cookery series, some of Anton Mosimann's shows and some early efforts by Raymond Blanc.

In fact, the BBC Continuing Education Department, which made most of these, had a dedication to location filming of food shows. Floyd, though, had a greater appeal outside Britain, and his shows were seen and relished in most English-speaking countries, though he never achieved a big American audience.

Floyd himself was soon eclipsed, not only by TV chefs such as Jamie Oliver, Gordon Ramsay and Rick Stein, but by non-chefs such as Delia Smith and Nigella Lawson, all five of whom have become celebrities and made fortunes for themselves on a scale probably even beyond Floyd's ambitions, much though he complained that he was oppressed by being recognised on the street, and even being asked, "where's your glass of wine?" by would-be wits in airports as he was trying to catch his plane.

He had earned a good deal of money from his shows and 23 books, but he could not manage his finances, and, though he did finally buy the Bentley he longed for, he and his money were soon and often parted. In his last year the frail 63-year-old was reduced to performing a one-man show in provincial theatres, where the ticket price included a glass of red wine. Sometimes there were repeats of segments of his series on some of Britain's morning shows, but on the continuous loop of satellite broadcasting he was always present at any hour you switched on: "Oh, my shows are screened as educational aids in the Kuwait or Brunei, to help people improve their English," he said "blithely" to Rushton. "All these shows are on all over the world and I don't get a penny."

There must have been some bitterness in the remark as well, for in 2006 he was actually diagnosed with malnutrition, which he claimed was caused by getting back to hotels late at night and by having constant jetlag. He had already had a minor stroke in 2002. Underlying it all was alcoholism: he thought of himself as just an affable "boozer," but in 2004 he was convicted of drink-driving and banned for 32 months. In 2007 he told his interviewer that "I'd prefer to work less, but I wouldn't give up at all, no, no. I wouldn't do it if I couldn't put my heart into it. I'm not cynical at all." He had hoped that the Maltsters Arms, a gastropub at Tuckenhaye on the banks of the River Dart that he owned at the beginning of the 1990s would be his pension. After making Floyd's American Pie in 1989, the last programme he did for the BBC, he bought the pub for £320,000 and spent another £350,000 getting it into shape.

He did not stay in business for long before it went bust. One problem was that he left the restaurant and went to film in Australia. In the past some of his friends had said he blamed the head chef, the accomplished and romantic-looking Jean-Christophe Novelli, for "stuffing too much foie gras in the pigs trotters." But Floyd himself admitted that the cause of the failure in 1996 was that he was "a shockingly bad" businessman.

One restaurant still trades under Floyd's name, at the Burasari resort in Phuket, Thailand. "I was there on holiday with my wife and the manager overheard me saying how we should move there. He asked me if I wanted to open a restaurant in the hotel." Though Floyd wrote the menus, the resort owner had total management and financial control. In the last few years Floyd's principal home was in Avignon, France, and his visits to England were brief.

Born at the end of 1943 near Reading to working-class parents, Sydney and Winnifred, he grew up in Somerset. His family somehow found the funds to send him to Wellington School there – the same minor public school that Jeffrey Archer attended. Leaving school, his first job was as a cub reporter at the Bristol Evening Post, where he caught the editor's fancy, and was made his assistant, which gave the bow-tied, sharply dressed teenager a taste for eating on expenses in fancy restaurants. Floyd said that it was seeing the film Zulu that made him think of joining the Army. In 1963 he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment, but didn't last long because, he said, he spent more time in the mess than in a tank. He told another interviewer, Lynn Barber, that "he slid into catering simply by dint of having failed at everything else."

After the army he briefly had a restaurant in France, then in Bristol, aged 28, had three or four eateries, ranging from a bistro to a posh chop house. The style of his 1970s food was in part derived from his mother's 1950s cooking in Somerset, perforce seasonal and dependent on local ingredients – in his stage shows he spoke nostalgically about the faggots she made from pig's brains and the enormous bowls of crusted clotted cream in her larder. Barber said that, "as a restaurateur he was almost a success, but he forgot the essential requirement of making money. The bailiffs and the bank managers were already at the door when he was talent-spotted by Pritchard". He did a cookery spot for him at Plymouth then made the pilot show for the BBC, which led to the triumph of Floyd on Fish.

Besides money, the other aspect of life Floyd found difficult was women. To pay for his divorce from his first wife, Jesmond, by whom he had a son, Patrick, he sold the Bristol restaurants – using the remainder of the cash to buy a boat he named "Flirty," and sailed around the Mediterranean for the next two years. He went bust again, was bailed out by friends, and somehow raised the money to start the final Bristol restaurant. His wives then got ever younger. In 1983 he married Julie Hatcher, 10 years younger, and had a daughter, Poppy. In 1991 he proposed to his third wife, Shaunagh, four hours after meeting her in the pub he then owned. He was 23 years older than her; they divorced after three years. As Barber wrote around this time, "Everyone who knows Keith Floyd agrees that he has not changed at all. He was always a monster egomaniac, always drunk, always paranoid, and he still is."

Once he decided that Shaunagh had forgotten his post-Christmas birthday and threw her and 50 diners out of his pub. In 1995 he married Tess Smith, a food stylist. He told Rushton in 2007 that the marriage was still solid, "although travelling makes things hard. She wants to be in England for her parents, and I prefer to live in France." The next night, on stage at the Pocklington Arts Centre in North Yorkshire, Floyd told his audience that they were getting divorced.

Paul Levy

Keith Floyd, cook, restaurateur and broadcaster: born near Reading 28 December 1943; married 1971 Jesmond (divorced, one son), 1983 Julie Hatcher (divorced, one daughter), 1991 Shaunagh Mullett (divorced), 1995 Theresa Mary Smith (divorced); died Bridport, Dorset 14 September 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks