Judith Kerr: Writer and illustrator best known for ‘The Tiger Who Came to Tea’

She complemented her storytelling skills with visuals that brought magic to the lives of generations of children

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Petite, quizzical and with a never-ending enthusiasm for life, Judith Kerr, who has died aged 95, was best known as the author of The Tiger Who Came to Tea and When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit. The latter, autobiographical story, unforgettably describes the 20-century refugee experience as reflected in the life of one person.

Although she never shirked from the truth, her book was infused with such charm and grace that it soon became a particular favourite with generations of young readers. She was also a brilliant illustrator with many titles to her name. Born in Berlin in 1923, Kerr was the second child of Alfred Kerr, a renowned German Jewish writer and an active anti-fascist. Her mother was a musician, and the family lived a comfortable life until the Nazis came to power in 1933.

Knowing there was a price on his head, Kerr took his family out of Germany on the same day, leaving behind nearly all its possessions including Kerr’s favourite toy pink rabbit, to be immortalised years later. The move was just in time, with the police coming round next morning to search for the family’s passports. Kerr’s description of the train journey to Switzerland, when she nearly gave the family away in a fit of temper, makes riveting reading.

Moving on to Paris and then to London, Kerr attended 11 schools in four different countries. She continued to thrive wherever she was, although the rest of her family had a tougher time.

Once in Britain, her older brother – later to become an eminent QC – was interned as an enemy alien. Her father remained unemployed and her mother was forced to do menial jobs. There was never any money, and life in a cheap hotel crowded with other refugees was hard. Yet Kerr remained unbowed, soon fluent in English and studying art in the evenings after leaving school at 16 and taking a job as secretary to the Red Cross for the next four years.

In 1945 she won a scholarship to study at London’s Central School of Art and Crafts. Eventually teaching art at a technical school, she met her future husband Nigel Kneale, always referred to in the family as Tom, when he was working across the road at the BBC’s television studio.

Marrying him after the huge success of his famous Quatermass series, she also moved to the BBC as a reader and scriptwriter, responsible among other things for a six-part adaptation of a John Buchan novel. Two children were born, one of whom, Matthew Kneale, was later to become a well-known writer.

Settling down as a full-time mother, Kerr decided to write her autobiographical novel as a way of remembering the now deceased parents she had so adored. She also wanted her children to know about the turbulent times she had lived through, but added with typical lack of self-pity that: “I wanted also to explain that it wasn’t nearly as horrific as it sounded.”

The result was When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (1971), with Kerr appearing as the irrepressible Anna but everything else happening as it did. Anna is shown as being able to survive the constant moves and uncertainty because of the security that the love of her family allowed her, with parents who always managed to make the next journey seem like one big adventure. The book was an instant success, and much translated.

It was followed four years later by the second part of the trilogy, The Other Way Round (1975). Here, 18-year-old Anna has her first real moment of fear when she is faced with moving away from her parents for the first time. The third and last book, A Small Person Far Away (1978), is an altogether sadder work. Her father had died in 1948, a disappointed man whose once famed talents stayed unused for the last half of his life.

After his death, at a time for the family which even Kerr admitted was exceptionally bleak, her mother moved back to Germany but then attempted suicide. In the story Anna goes out to see her, full of hope for the baby she is now carrying but more aware now of the toll that history had taken upon her parents.

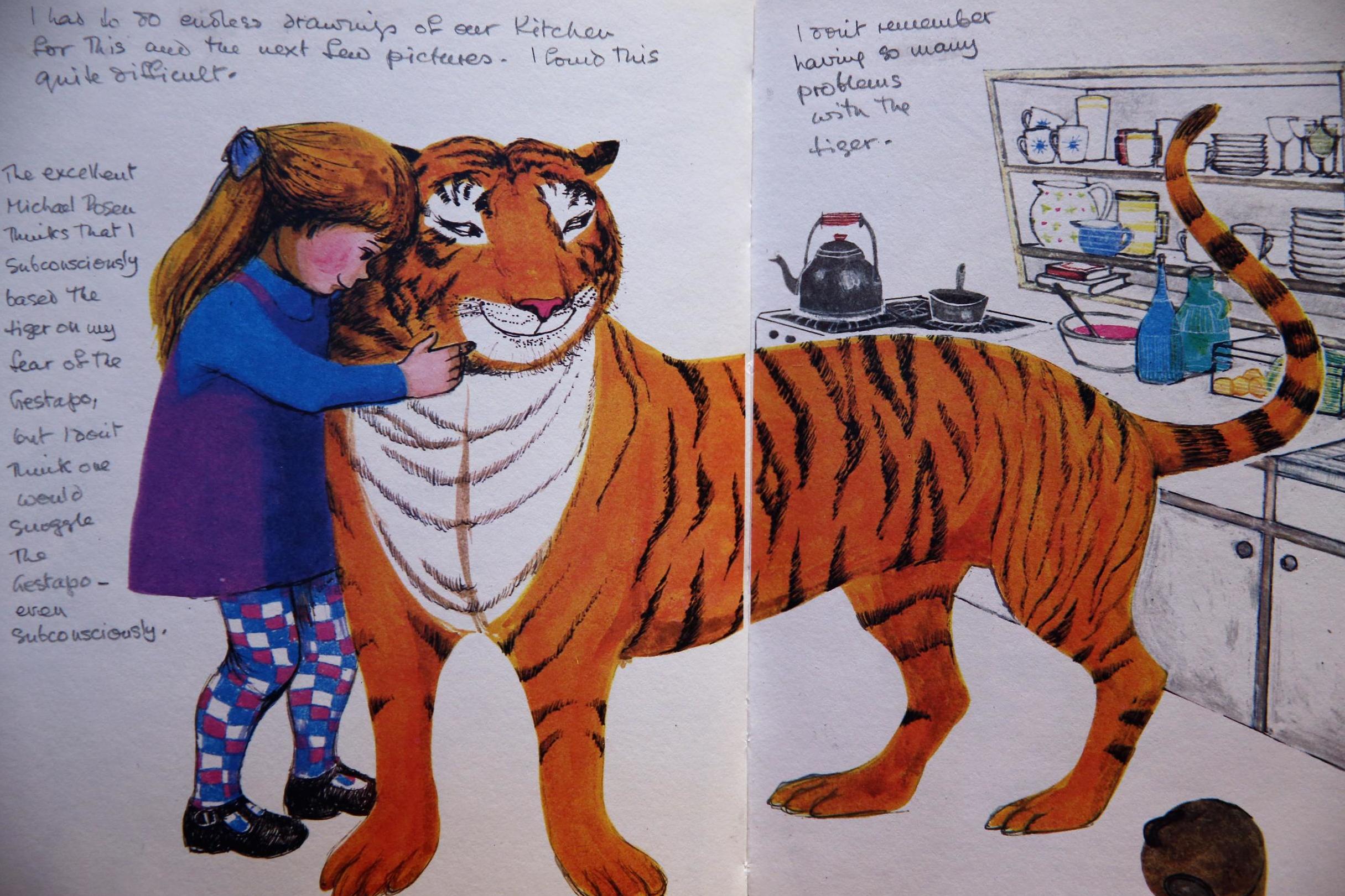

By now Kerr was also a well-known illustrator, whose picture book The Tiger Who Came to Tea (1968) was already something of a classic. Arising, as with many of her other books, from a light-hearted suggestion made by her children, it tells the story of a suburban mother and child whose house is entered without warning by a ravenous tiger.

Eating and drinking everything he sees, he finally departs, leaving the little family with neither food nor thanks for its trouble. When father returns from work, he deals with the situation in the most positive way, taking everyone out for a jolly supper. Some have seen this story as a parable about the impact of all-devouring, invasive fascism upon an ordinary but now targeted family; a view the author did not take seriously.

Kerr’s other great success came from her Mog picture books, based on the family cat of the same name. Uncluttered and direct, her artwork was always popular with small readers. The first book, Mog, the Forgetful Cat (1971), set the tone for the next three decades, with Mog herself a pleasant but not particularly bright animal, owned by the Thomas family and much given to dreaming.

The good she does, such as surprising a burglar one evening, happens by accident, with Mog otherwise content to pass as much time as possible comfortably asleep. A main character with such transparent faults, and therefore in no position to preach or set any sort of example, also proved most acceptable to infants over the years.

When Mog finally dies in Goodbye Mog (2003), she stays on for a while as a short-tempered ghost in order to tutor her successor Rumpus, a ginger kitten. This particular title led to considerable interest in the press for its frank approach to the death of a favourite character; an unusual topic in picture books aimed at the very young, but beautifully handled in these pages.

Kerr, who in 2012 was given an OBE for services to children’s literature and Holocaust education, received a lifetime achievement award from literary charity BookTrust in 2016.

Enjoying her house overlooking Barnes common, where she had lived for many years, and appearing on Desert Island Discs in 2004 to great acclaim, Kerr remained happily married and glorying in her family, now extending to grandchildren as well. In 2006 her husband died. But with typical courage, Kerr reacted to this tragic loss by producing yet more picture books, including My Henry (2011).

Set in a retirement home, this delightful books shows a couple – very much like Kerr and Tom – meeting every afternoon to have adventures flying through the air, even though the little old lady is still alive but her husband is now a ghost. The generosity of spirit that shines through this book and indeed all her work is testament to a truly remarkable person.

Judith Kerr, children’s writer and illustrator, born Berlin, Germany 14 June 1923, died 22 May 2019

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments