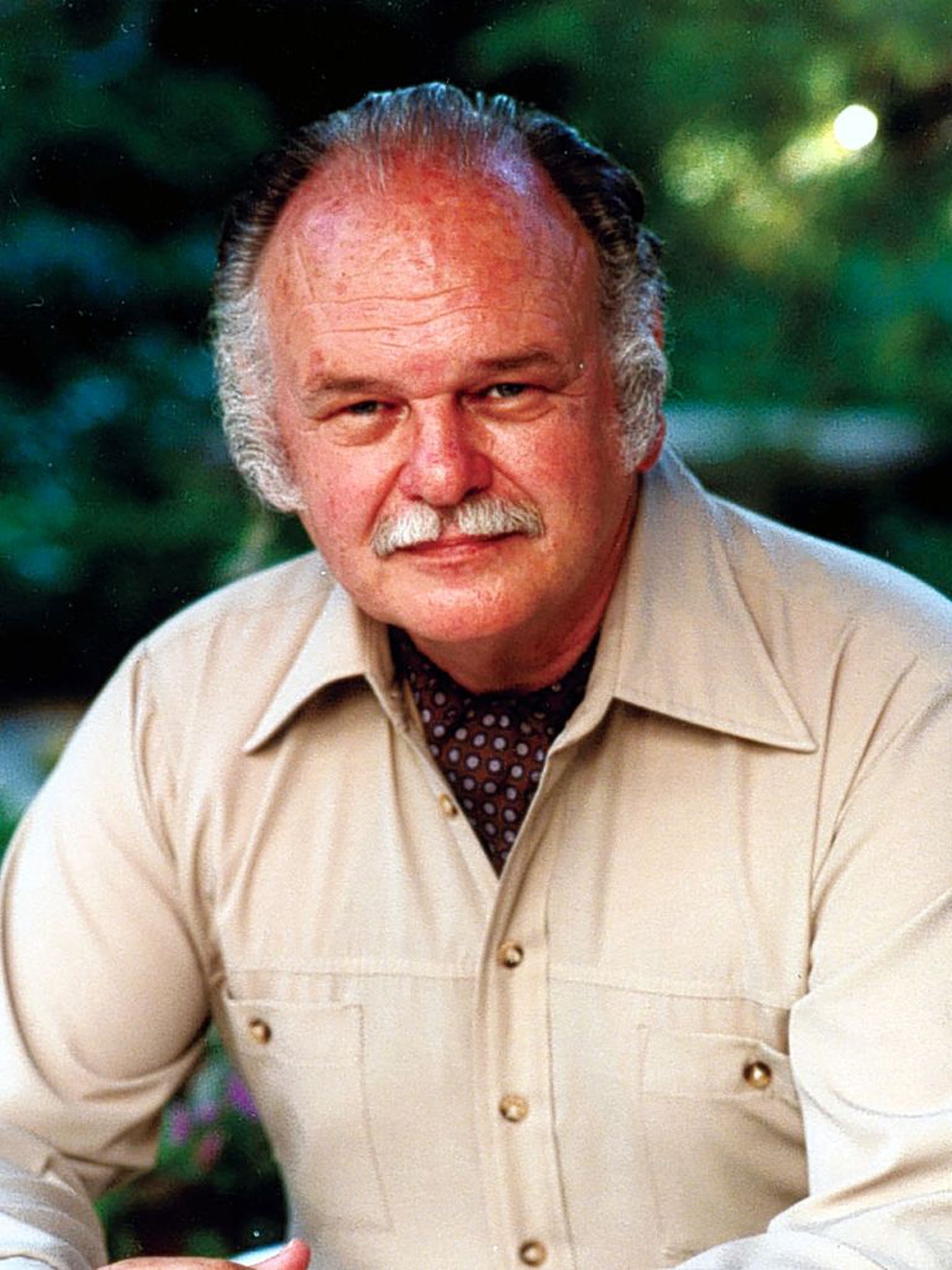

Jon Manchip White: Novelist who fell out of love with Britain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jon Manchip White was primarily a narrator of extraordinary events which take place in exotic settings. Most of his novels, some 20 in all, have to do with a race, or an escape, or a test of endurance, skill or moral fibre. Not strong on characterisation, he was an adroit raconteur and liked gripping yarns.

He had a penchant for people past their prime and there is more than a touch of Hemingway in his preoccupation with physical ordeals and the minutiae of military training, the weaponry and equipment of his protagonists, often soldiers and sportsmen. His first novel, Mask of Dust (1953), is about the world of the Grand Prix, set in northern Italy, regarded by the crowd as the modern equivalent of charioteering. The hero is a British driver who has been a fighter pilot and attempts to prove he has not lost his nerve and expertise so he might retain the favours of his young wife.

Another favourite theme is the reward or punishment of antisocial behaviour. In three of his novels the main character is on the run from conventional society: in No Home But Heaven (1956) a gypsy is in conflict with the welfare state; The Mercenaries (1958) is an escape drama set in Argentina after the fall of Peron; Hour of the Rat (1962) deals with the trial of a British civil servant who has killed a member of a Japanese delegation, his former persecutor in a prisoner of war camp.

White defended himself against his critics by lamenting the decline of the novel in Britain and the taste for large themes and broad canvases. "The solid, educated, extensive, cultural, book-buying class with its knowledge of and interest in the great world to whom the British novelist once addressed himself has vanished," he wrote in 1972. "The novelist is now uncertain of the nature and character of his reader. Since they celebrate the qualities of energy and ambition, novels of my kind are not popular in Britain. When British life has regained some of its native vigour and breadth, the characters and situations that novelists like me write about will be more in fashion."

He was born in Cardiff in 1924. His comfortable home was in Cathedral Road, one of the city's grandest boulevards. His father was the only member of his family not to go to sea, though he made a living as part-owner of a shipping company. The slump was having a severe effect and his father struggled to stave off bankruptcy. In 1932 he contracted tuberculosis and his son was sent to a boarding school in London. During the holidays he was employed by the Western Mail as Our Theatre Correspondent.

White decided the best way to reverse the decline of his family's fortunes was to win a scholarship to university, and he entered St Catherine's College, Cambridge, with an Open Exhibition in English in 1942. The year following he joined the Naval Training Unit and served on naval convoys. As hostilities drew to a close, he was transferred to the Welsh Guards. He met his wife, Valerie, a nurse, during the VE Day celebrations.

He returned to Cambridge and took a degree in English, Prehistoric Archaeology and Oriental Languages. Shortly afterwards he was given a job with the Keeper of the Egyptian and Assyrian Department at the British Museum. He published in the fields of anthropology and Egyptology and edited a number of important texts such as Harold Carter's The Tomb of Tutankhamun (1972).

By 1956 he knew he wanted to be a writer. He had published two slim volumes of verse but wanted more experience that could go to writing novels. He had joined the BBC as a story editor, and also began writing original dramas. In 1960 he left the Foreign Service to write full-time. Among his books published during the 1960s were Marshall of France: The Life and Times of Maurice, Comte de Saxe (1962), and the study Diego Velazques, Painter and Courtier (1969). A substantial collection of his poems appeared as The Mountain Lion in 1971.

In 1965 he moved to the US, a place which had engaged his sympathies since his time in Cambridge, when he had written a dissertation on the Pueblo Indians. In 1967 he was appointed writer-in-residence at the University of Texas at El Paso. Ten years later he moved to Knoxville, where he became Professor of English. He became a US citizen in the 1970s.

Two novels of this period are perhaps among his best: Nightclimber (1968) and The Game of Troy (1971). In the first the hero is an art historian who is prey to the habit, said to be in vogue in pre-war Cambridge, of climbing high buildings, and whose obsession is exploited by a millionaire collector in search of mysterious Greek treasure.. In The Game of Troy a strain of phantasmagoria appeared in his writing. The plot is based on the legend of the Minotaur. The central character, an architect, is commissioned by a Texas millionaire with whose wife he has fallen in love to make a labyrinth. He finds himself being pursued by the murderous husband through this nightmarish maze as the story reaches its bloody climax.

His right-of-centre politics – he sneered at "socialists and crypto-socialists" and was especially caustic about New Statesman readers – were expressed in What to Do When the Russians Come: a Survivor's Handbook (1984), an hysterical tract warning that the Soviet Union was about to engulf the world, which he wrote with Robert Conquest.

Although he kept in touch with friends in Wales, White was not remembered in the land of his birth. When my Oxford Companion to the Literature of Wales appeared in 1986 he wrote me a tart letter complaining he had been omitted.

At the time of avisit to Cardiff in 1990 he was writing a memoir which appeared as The Journeying Boy: Scenes from a Welsh Childhood (1991). It is an attempt to lay ghosts of his past, particularly his father's consumption, and takes the form of an expatriate's fond memories of a city and its docklands which had changed so much that he barely recognised them.

Jon Manchip White, writer: born Cardiff 23 June 1924; married 1946 Valerie Leighton (deceased; two daughters); died Knoxville, Tennessee 31 July 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments