Johnny Winter: Guitarist whose blistering slide-playing made him a favourite from Woodstock to the Royal Albert Hall

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

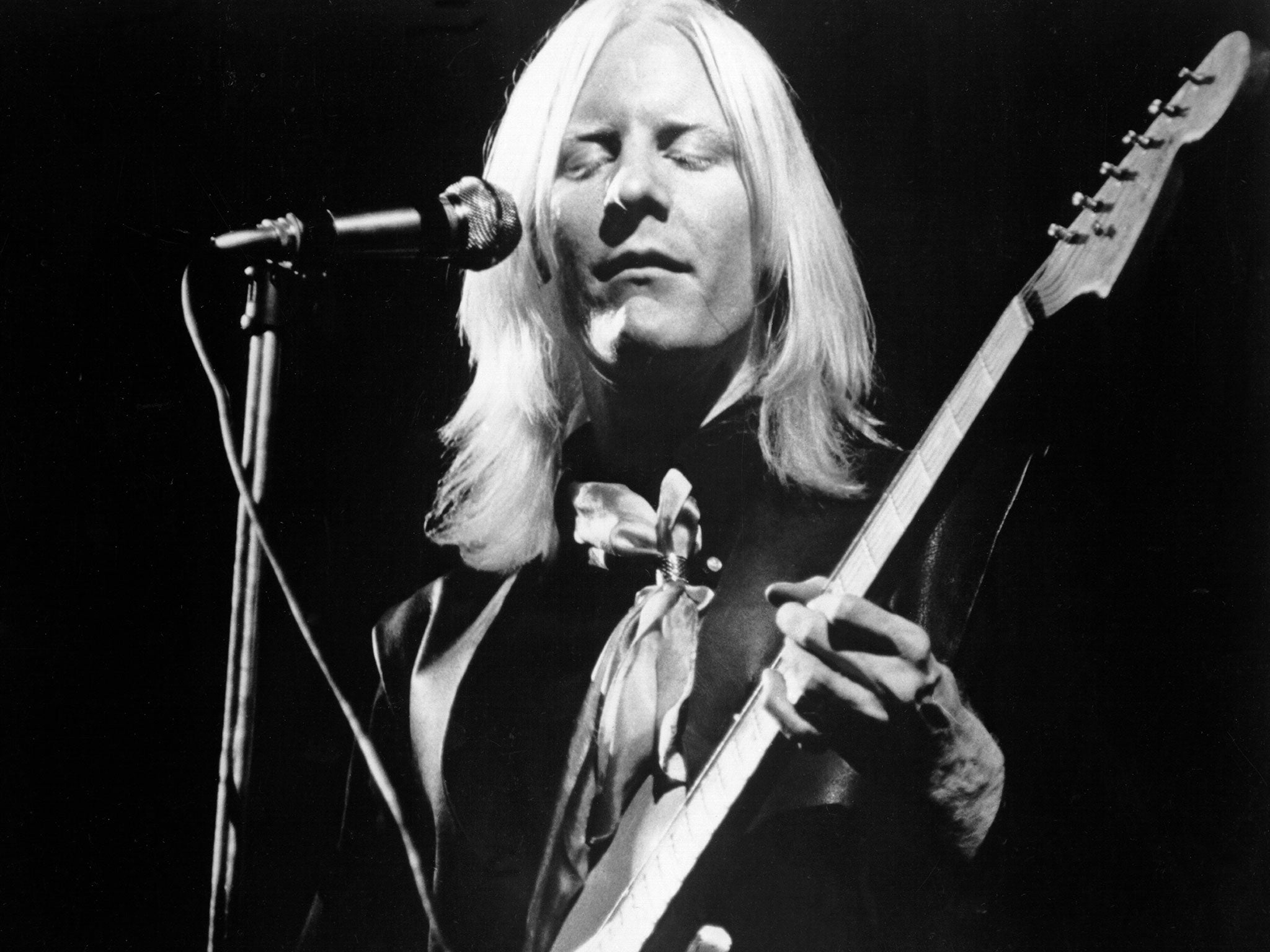

Your support makes all the difference.When he emerged in the late 1960s Johnny Winter stood out as much because of his appearance as for the blistering solos and soaring slide technique that became his trademarks and made him a favourite with audiences from the Woodstock festival to London's Royal Albert Hall.

Described as a "130-pound cross-eyed albino bluesman with long fleecy hair playing some of the gutsiest blues guitar you have ever heard" by Rolling Stone in 1968, Winter cut a distinctive figure and is rightly listed among the 100 Greatest Guitarists of all time by the same publication. A lightning fast player also capable of great finesse, he was highly rated by contemporaries like Jimi Hendrix, with whom he occasionally jammed, and the blues legend Muddy Waters, whose career he helped revive in the 1970s with a series of Grammy-winning albums.

Winter used a thumb-pick on his right hand and a slide on the little finger of his left hand and tended to favour the Gibson Firebird. He influenced several generations of players including Eddie Van Halen, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Joe Satriani, Slash of Guns N' Roses and Joe Bonamassa who, along with Eric Clapton, ZZ Top's Billy Gibbons, Joe Perry of Aerosmith and Leslie West, guest on Step Back, his studio set due in September.

John Dawson Winter III always felt closer to Leland, Mississippi, where his father ran a cotton business, than Beaumont, Texas, where he was born in 1944. ""I loved Mississippi," he said. "All the blues in the world came from there." By the time his younger brother Edgar was born in 1947, the Winters had moved to Beaumont, where their father sang in the church choir and a barbershop quartet and played saxophone in swing-era bands. Johnny took up the clarinet aged five but switched to the ukulele. "Later on, when I was 11 or 12 and my hands were bigger, I started on a guitar that was handed down from my grandpa. I just practised and practised. I could do it because I loved it so much."

Johnny and Edgar were keen radio listeners, tuning in to the local station that played rhythm and blues records sometimes introduced by JP Richardson – later The Big Bopper of "Chantilly Lace'' fame. By 1959, the brothers were playing talent shows and travelled to New York to audition for The Original Amateur Hour. Back in Beaumont, they began sneaking into black clubs, where they stood out because of their albinism, but were welcomed by the clientèle, including a night in 1962 when Johnny got up on stage at The Raven to jam with BB King. "I was about 17 and he asked me for a union card, and I had one," he remembered. "He gave me his guitar and let me play. I got a standing ovation, and he took his guitar back!"

Johnny recorded several singles for local labels, including "Eternally'', with horn arrangements by Edgar, which was picked up by Atlantic and found favour in Texas and Lousiana. Following a spell in Chicago he returned South and began developing a fearsome reputation as the frontman of a power trio with Tommy Shannon on bass and Uncle John Turner on drums.

This led to an article in Rolling Stone that called Winter "the hottest item outside Janis Joplin" and caught the eye of Steve Paul, owner of the hip New York club The Scene who managed the McCoys. Paul brought Winter to New York, where he guested with Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper at the Fillmore East. His rendition of BB King's "It's My Own Fault'' brought the house down and was witnessed by Columbia Records head Clive Davis, who signed Winter to a deal reportedly worth $600,000 over five years and gave him carte blanche to record and produce the Johnny Winter album in Nashville. "It was a gigantic moment for me," he said.

He soon had two records in the charts, his eponymous Columbia debut, featuring a storming version of Sonny Boy Williamson's "Good Morning Little Schoolgirl'' that remained a staple of his repertoire, and The Progressive Blues Experiment. He appeared at Woodstock but his manager couldn't reach an agreement for him to be included in the documentary or the two live sets issued the following year, when he released Second Winter, a three-sided album (with a blank fourth side) containing superlative takes on "Johnny B Goode" and "Highway 61 Revisited".

When his rhythm section quit in 1970, Paul teamed him up with the McCoys, including guitarist, singer and songwriter Rick Derringer. The new line-up charted on both sides of the Atlantic with Johnny Winter And, as well as Live Johnny Winter And, featuring his barnstorming version of the Rolling Stones' "Jumpin' Jack Flash'' which became his biggest US hit in 1971 and so impressed the originators they let him record another of their songs, "Silver Train'', before issuing their own version on Goats Head Soup in 1973.

By then, Winter was battling heroin addiction and was encouraged by Paul to take a break and clean up. When he returned with 1973's Still Alive And Well, his highest-charting US album, he gave a series of frank interviews that did much to jolt the music industry out of its laissez faire attitude towards drug-taking. "I hated myself. I couldn't even think about eating, changing clothes, playing jobs or anything," said Winter at the time, though he continued to struggle with alcohol and methadone dependency for another two decades.

Never a prolific songwriter, Winter remained a supreme interpreter of the blues, equally adept at the Mississippi Delta or Chicago styles, and proved his mettle as producer and second guitarist on Hard Again, I'm Ready, Muddy "Mississippi'' Waters – Live and King Bee, four Muddy Waters albums between 1977 and 1980 whose success prompted the bluesman to call him his "adopted son".

When I saw him at Bob Dylan's 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration at Madison Square Garden in 1992, he could still deliver a mean ''Highway 61 Revisited'' but last year at a small provincial venue in Annemasse, he performed sitting down, as he had done for over a decade, and was a ghostly presence, his pale arms covered in tattoos. He was found dead in his hotel room in Bülach, near Zurich, two days after playing his last concert, at the Cahors Blues Festival in France.

"An albino belongs to the smallest minority there is," he once reflected. "Maybe that's why I went for the blues."

PIERRE PERRONE

John Dawson Winter III, musician: born Beaumont, Texas 23 February 1944; married; died Bülach, Switzerland 16 July 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments