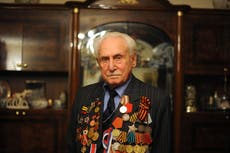

Johnny Johnson: Last surviving dambuster

The pilot was part of 617 Squadron whose highly accurate deployment of innovative ‘bouncing’ bombs caused huge damage across Germany’s Ruhr valley industrial heartland

Lying on his stomach right in the Lancaster’s nose, George “Johnny” Johnson had the German dam in his sights. This was the Sorpe, the hardest nut to crack of all the British raiders’ targets, a concrete core protected by a mound of earth, and he had to aim the bomb.

The huge aircraft, AJ-T Tommy, dived towards the Sorpe for the 10th time, the four Merlin engines singing. For the 10th time it buzzed the church steeple of the village of Langscheid, then roared down, passing again along the dam’s length to 30ft above the moonlit rim, over the crucial place.

“Bomb gone!” Johnson announced this time. The Lanc hurtled upwards, just clearing the 1,000ft hill beyond the dam’s far bank.

“Thank Christ for that,” came the riposte. The crew of seven, led by pilot “Big Joe” McCarthy, had spent half an hour perfecting their position for just this one shot, to be made with the experimental four-ton cylindrical bomb codenamed “Upkeep”. The bomb, which all the way from RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire had hung under the aircraft on enormous callipers, reminded Johnson of a giant dustbin.

Upkeep, invented by the aircraft designer Sir Barnes Wallis, was considered Britain’s best hope at having a crack at the might of the Reich’s industrial heartland, the Ruhr. Having come so far, Johnson was not going to put it awry.

But Johnson’s bomb, unlike those carried by other aircraft of 617 Squadron on the raid on Nazi Germany’s industrial dams on the night of 16-17 May 1943, was neither to spin nor to bounce, but had to land on the Sorpe’s crest exactly halfway along the 2,000ft length, and only then, like its fellows, roll down, and be set off by water-pressure. This was the hardest and least-rehearsed-for drop, and Johnson knew that Wallis thought the Sorpe would need six direct hits to burst. The other target dams, built differently, would, it was calculated, crack with fewer.

So it proved: Lancasters flying with the raid’s leader, Wing Cdr Guy Gibson, breached two dams, the Mohne and the Eder, with a couple of bombs each, but although Johnson caused a 1,000ft fountain and damaged 20ft along the crest, and his fellow bomb-aimer, Stefan Oancia, in AJ F-Freddie, piloted by Ken Brown, and arriving a couple of hours later, extended the damage to 300ft, the Sorpe still stood.

Johnson would later watch wryly the 1955 film about the raid, starring Richard Todd as Gibson, which, he observed, contained many inaccuracies. It also gave little mention to the Sorpe. Johnson would also, many years on, become a consultant to the filmmaker Sir Peter Jackson, for a new version that has not yet appeared.

Left out, in the 1955 film was McCarthy’s dash with his crew from their designated Lancaster AJ-Q Queenie, which developed a leak just before take-off, to the spare AJ-T Tommy, only to find vital compass cards – crucial for keeping to the planned route – missing, and be helped by their valued aide “Chiefy” Powell, of the ground crew, to calm down.

Neither is any mention made of T Tommy’s hazardous landing back at Scampton, with a tyre shredded after the aircraft was fired on from a German armoured freight train encountered on the outward journey.

Johnson’s part in the raid earned him the Distinguished Flying Medal. For the farm foreman’s son who had expected to spend his working life as a lowly municipal park-keeper, the investiture a month later at Buckingham Palace, when he received his decoration from King George VI’s consort Queen Elizabeth, was a watershed.

He and his wife Gwyneth, a coalminer’s daughter whose work was as a telephone operator during the war, were to find themselves catapulted into Britain’s then rigidly defined officer class, both by the war’s talent-revealing needs, and by the raid’s prestige.

“He’s one of the Dambusters and he’s here to see his wife,” a guard was heard being admonished soon after it. “You can’t talk to him like that!”

Johnson had already flown a full tour of missions, first as a gunner, then as a bomb-aimer, as a member of McCarthy’s crew in 97 Sqn out of Woodhall Spa, Lincolnshire, before the dams raid, and would go on to others, including the celebrated moonlight drops over France of SOE agents and their supplies, from Tempsford aerodrome in Bedfordshire.

On one raid, under a later commanding officer of the 617 Squadron, group captain Sir Leonard Cheshire, later Lord Cheshire, VC, on 16 March 1944, Johnson managed to aim a 12,000lb blast bomb destined for the Michelin tyre factory at Clermont-Ferrand in France so accurately that the workshops were destroyed, but the workers’ canteen was left unharmed.

Johnson also flew missions to destroy the hidden woodland sites from which the Nazis’ V1 Doodlebug flying bombs were launched, bringing new terror to London, in the summer of 1944.

Johnson had been promoted to pilot officer in November 1943, and at the war’s end was offered a permanent commission. He stayed in the RAF as a weapons specialist.

At about the time he was posted to RAF Kinloss in northern Scotland, in the early 1950s, he was selected as one of those the RAF wanted to operate its next generation of aircraft, the V-force which would include the delta-wing Avro Vulcan that would still be flying in the 1980s.

But to Johnson, whose mother had died when he was three, and who had endured hardship and a loveless family life in his native Lincolnshire, it seemed the strain on his relationship with his wife and three children, which he treasured, would be too much. He refused, and after more postings including three years in Singapore, he left the RAF in 1962 to become a school biology teacher.

This to Johnson, was another triumph: the taciturn boy he had been was now a confident instructor. He even ran courses for inmates at Rampton Secure Hospital for psychiatric patients in Nottinghamshire. In retirement he became for a time a local Conservative councillor in Torquay, Devon.

Johnson was educated in Lincolnshire, then at Lord Wandsworth’s College, Hampshire. He volunteered for the RAF in 1940, and took a pilot’s course in Florida before training as a gunner. He published a memoir, The Last British Dambuster, in 2014.

By the end of August 2015, after the death of the last pilot, the New Zealander Les Munro, on 4 August, only Johnson and a Canadian, the gunner Fred Sutherland, were still alive from the men who went on the raid, in which eight of the Lancasters were lost, with 53 killed and three taken prisoner.

George Leonard Johnson, DFM, airman and teacher, born 25 November 1921, died 7 December 2022

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks