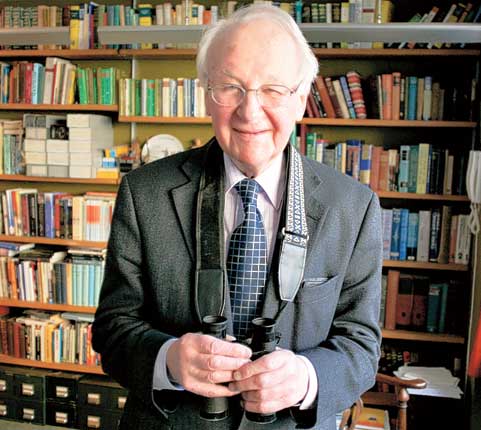

John Stott: Preacher and writer who exerted a colossal influence on evangelical Christianity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few churchmen become the subjects of doctoral theses. The life and influence of John Stott, Chaplain to the Queen, university missioner on six continents, and statesman theologian, has attracted original research in 10 universities. His name appeared in Time magazine in April 2005 in the company of Condoleezza Rice and Oprah Winfrey as "one of the 100 most influential figures in the world". A New York Times op ed that year declared that if evangelicals could elect a pope, Stott would be that man.

Stott's father, a life-long agnostic, wanted his son to find a career in the diplomatic service, for which his sharp instinct and eirenic manner would have suited him well. But Stott faced a major turning point as a schoolboy at Rugby when he heard an address by EJH Nash, staff of the Varsity and Public Schools branch of the Scripture Union. Nash saw the strategic potential of boys in the top public schools, and ran annual camps for them at Iwerne Minster in Dorset (then widely known as "Bash camps", now simply as "Iwerne Holidays") to teach them the Bible and the art of leadership. These camps have raised up leading figures in academia, the church, politics and the armed forces. Stott acted as camp treasurer and secretary for several years.

Sensing a call to ordination from his schooldays, John Stott had sought exemption from war service. His pacifist stance caused much anguish to his father, a major general in the Medical Corps. The relationship between father and son was never fully repaired and this remained a source of deep regret to Stott for the rest of his life. On reflection, he felt the just-war theory had never been explained to him, and that his position would have been different had he engaged with it.

Stott entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1939, attaining a double first in modern languages before reading theology at Ridley Hall. Alongside Nash, with whom he corresponded weekly, the second moulding influence on him was the Cambridge Inter-Collegiate Christian Union (CICCU). While never a CICCU member (a promise made to his father before going up), he made an energetic contribution to its life. Now his future path was set, firmly committed to "the twin authorities of the Bible and the person of Jesus Christ". In his ninth decade he still described himself as "a product of Iwerne and the CICCU", remaining an Honorary Vice President of the CICCU until his death.

In 1945 Stott became assistant curate at All Souls Church, Langham Place, where he had grown up through Sunday school. In 1950, at only 29, he succeeded Harold Earnshaw-Smith as rector – a prestigious West End appointment in the gift of the Crown.

Stott was resolute that All Souls should serve its cosmopolitan inner-city parish, and not just the well-educated. He took parish children camping each year, giving them a daily wake-up call on his piano accordion. His urbane manner and RP pronunciation evidently caused no small amusement, for it was rumoured that his middle initials stood for Rochester Winchester. In 1958 he founded the All Souls Clubhouse in the parish, a daring experiment in youth and community work 20 years ahead of its time.

In 1975, when Stott became Rector Emeritus of All Souls, a mews flat was built for him above the garage behind the Weymouth Street rectory. This modest one-bedroom home, with its tiny kitchen and book-lined walls, reflected the simple lifestyle he preferred.

In 1954 Stott purchased a remote farmhouse on the Pembrokeshire coast from Peter Conder, when Conder was appointed Director of the RSPB. From a state of dereliction, without mains, water or a road to its boundary, "The Hookses" was restored gradually by working parties to become Stott's writing base, and to welcome student house parties and groups from church. Electricity was finally installed in 2001.

The American evangelist Billy Graham first met Stott in 1954, when thousands poured nightly into Harringay Stadium, including busloads from All Souls Church. It was to prove a strong friendship. In 1974, at Graham's seminal Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization, Stott was appointed chief architect of its landmark Lausanne Covenant. Long before that, in 1955, Graham invited Stott to co-lead a major evangelistic mission to Cambridge University. (Stott had himself led the previous Cambridge mission three years earlier.) Each held the other in high regard and a joke is told of how they would go round and round in the revolving door of the University Arms Hotel where they were both staying, each deferring to the other in not wanting to get out first!

While Billy Graham filled football stadia, Stott's arena was the university. The goal of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students (IFES), to make Christ known in every university in the world, was, he said, "the most strategic work imaginable". In week-long missions to universities, he would deliver nightly lectures with a characteristic blend of heraldic proclamation and carefully argued apologetics. His close links with university Christian Unions gave him unique access to some of the sharpest up-and-coming minds. He would hand-pick students and graduates to look with him at some of the new frontiers. They included future professors of bioethics, medicine and theology.

Perhaps two of the movements in which he held honorary office until his death best sum up his aspiration for the global Church. They are Langham Partnership International and The Lausanne Movement. He established Langham Partnership in 2002, under the leadership of Christopher JH Wright, uniting and expanding three earlier initiatives: to train preachers in the developing world and provide books for them, and to fund doctoral scholarships for the developing world's most able theological thinkers.

Following the 1974 Lausanne Congress, John Stott provided organisational leadership to the nascent Lausanne Movement, a unique global network of reflective evangelical practitioners, now active in 200 nations. In 2004 he enthusiastically endorsed the appointment of the American missions leader, S Douglas Birdsall, its current Chairman.

Stott's books, numbering over 50, all written by dictation or in longhand, were translated into a total of 67 languages. He produced some of the most significant theological works of the 20th century, selling millions of copies. Titles included Basic Christianity (1958); Christ the Controversialist (1970); Issues Facing Christians Today (1984) and The Incomparable Christ (2000). His final book, The Radical Disciple, appeared in 2010, in Stott's words, "to say goodbye to my readers". The work he considered his best was The Cross of Christ (1986), addressing the central truths of the Atonement. It went into 20 languages, and was dedicated to Frances Whitehead, his secretary from 1956 to the time of his death. Accepting only a modest allowance, Stott donated all royalties in perpetuity to The Langham Partnership.

While a curate, Stott had disappeared for two days to experience life as a vagrant. As well as having a keen social conscience, he worked hard to understand other world views. Living a mere seven minutes' walk from Oxford Circus, he was never removed from popular culture with its changing emphases and fashions. In 1982 he founded the London Institute for Contemporary Christianity just off Oxford Street. Its courses draw participants from all over the world, learning how to apply biblical truth in their own context. The broadcaster and sociologist Elaine Storkey was Director for several years, succeeded by Mark Greene. The Institute expressed Stott's desire for the church to practise what he called "double listening", a phrase which gained wide currency: the art of listening not only to "the Word" [Scripture] but to "the world".

It is perhaps surprising that John Stott never became a bishop. He was invited to have his name put forward as Archbishop of Sydney in 1981 but declined for two reasons: his dream of the London Institute was about to take shape, and he felt an Australian would be a more appropriate appointment. In 1985 he was approached for a British see, that of Winchester. The delay in such an approach (he was now 64) was presumably because of his evangelical convictions. After seeking advice from friends he declined, feeling his life had by then taken another direction.

What of the man himself? His father had taught him from boyhood: "close your mouth and open your ears", and this led to wide and informed interest in the natural world and especially in birdwatching. He saw 2,500 of the world's 9,000 bird species, writing of his love of birds in The Birds our Teachers (1999), nicknamed his "ornitheology". He was a humble man, keen to serve and to learn; People my Teachers (2002) profiles the lives of those from whom he learned much.

He considered marriage seriously at one stage, but remained a bachelor as his ministry was clearly set to involve demanding travel and writing commitments. He read widely and prepared his sermons with diligence, reckoning on an hour's preparation for each minute in the pulpit. He would rise daily at 5.0am, taking a "horizontal half-hour" after lunch. His longest appointments would be for one hour only.

He wrote of "iron self-discipline" as being a mark of a leader, but he was not an austere man. Quite the opposite. He was known throughout the world as Uncle John, and his pastoral touch, warm smile and sense of humour were trademark features of his ministry. When he enquired of me in 2005 how his great niece was getting on (then a new colleague of mine), I responded that she made me laugh. "Ah," he replied with a grin, and, landing each syllable in his sui generis way, added, "A forgotten charisma."

On becoming a Commander of the British Empire in 2006, Stott reflected on how friends might perceive this decoration, which he was honoured to accept. He wrote to them that while he was grateful the citation read "for services to Christian Scholarship and the Christian World", he was somewhat embarrassed by the continuing reference to the "'British Empire', which long ago ceased to exist!"

Stott's books, articles and papers were so extensive that a listing of his writings was published on its own as John Stott: a Comprehensive Bibliography (1995) compiled by his first biographer, Bishop Timothy Dudley-Smith. His papers are now deposited in the Lambeth Palace archive. His latest authorised biography, Inside Story by Roger Steer (IVP) appeared in 2009. Only eternity will judge the legacy of Stott's colossal endeavour.

Julia Cameron

John Robert Walmsley Stott, preacher and author: born London 27 April 1921; ordained 1945; Rector, All Souls, Langham Place 1950-75, then Emeritus; Chaplain to the Queen 1959-91, Extra Chaplain 1991-; founder, Evangelical Fellowship of the Anglican Communion 1961; initiator, National Evangelical Anglican Congresses, 1967-; chief architect of The Lausanne Covenant 1974; initiator, London Lectures in Contemporary Christianity 1975, Director, 1982–86, then President; Vice-President and Ambassador-at-Large, International Fellowship of Evangelical Students, 1979-; founder, Langham Trust 1969, Evangelical Literature Trust 1971, later Langham Partnership International; founding director, London Institute of Contemporary Christianity 1982; Honorary Chairman, The Lausanne Movement 2004-; five honorary doctorates, and Lambeth DD (1983); two 70th birthday Festschriften (UK and US, 1991); CBE 2006; died near Lingfield, Surrey 27 July 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments