John Rety: Poet and anarchist who ran the Hearing Eye publishing house

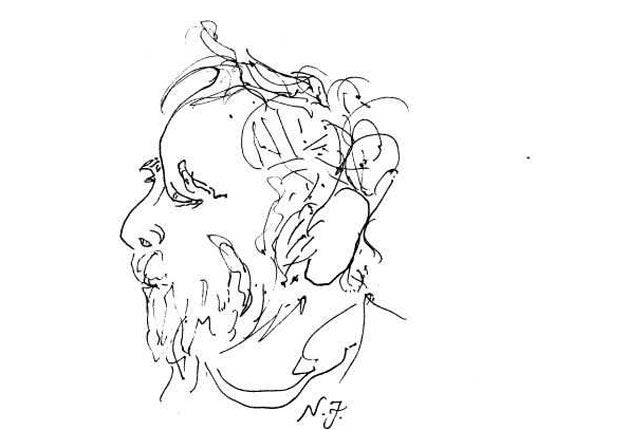

Though a writer of fiction and subsequently verse, John Rety was chiefly known for running the poetry publishing house, Hearing Eye, in conjunction with Torriano Meeting House in London's Kentish Town, where he hosted poetry readings. He was a character in every aspect of his being: nothing about him could have been other than it was, otherwise he would not have been John Rety: his physiognomy seemed the perfect expression of his personality, as did his accent, barely Hungarian, which he unselfconsciously called "educated". Shyly outgoing, he attracted all he met, even those who found him exasperating to work with. Only combs shunned him.

He was born in Budapest as Réti János, or, in his view, on reaching Britain in 1947 at the age of 17. In those days the granting of visas was rare, and the success of his application may be explained by his connection with British playwrights. Having found Budapest imprisoning, he became not just a new citizen but also a new person, freed by a new name. And yet while others pronounce 'Rety' with a short "e" – wits coined the word "retycence" – he himself always retained the long "a" sound of 'Réti'.

His grandfather and his father were theatrical agents, and while it would be far-fetched to say he was one too, Torriano Meeting House has a stage on which he invited poets to speak, and, indeed, perform, even harangue. The arts. Politics. The community. These were the fields that demanded engagement, and he offered a forum.

On his arrival in London he had worked for, and learnt from, a Mr Prager, who had a small publishing house. He had also studied art at the City and Guilds, which awarded him its Fine Art Diploma, but in 1977, his studio having been burgled, he turned to poetry.

Poetry he saw as the voice of freedom, and Freedom was the name of a magazine he edited. Then came the miners' strike. Mrs Thatcher's victory drew his mind back to Hungary's far-right Arrow Cross rather than to the Red Army that crushed it. About the failed revolution of 1956, during which his father died of a heart attack, he could be quite scathing. Maybe he associated it with the young Nazi Hungarian who, on 15 January, 1945, shot his grandmother when she told him that prudence now demanded the removal of his armband.

A communist, however, Rety was not. Already by the last stage of the European war, when he saw power take grotesque forms, he was an anarchist. In 2006, however, Morning Star dared invite him to become its poetry editor. The risk paid off: Thursdays, the day of the week when poems appear, saw a two per cent rise in circulation. Last year Hearing Eye published a selection entitled Well Versed. Tony Benn says in the introduction, "It is important to understand the close link between art and socialism." If this induces readers to expect an anthology of socialist poetry they will feel deceived: so wide-ranging is it that no single ideology emerges, unless freedom be classed as one.

The year 1982 saw the first poetry reading at Torriano Meeting House. Five years later the blind John Heath-Stubbs came to recite his poems about death, whereupon Rety told him, "They ought to be published, not necessarily by me." Through the post came the manuscript, Cats' Parnassus. Rety engaged his daughter, Emily Johns, to illustrate it. Hearing Eye was off to a good start, helped by Peter Levi's favourable review in The Times. Books by other poets followed before John Heath-Stubbs brought further success with his translations of the Roman poetess, Sulpicia. Hearing Eye's list now runs into three figures.

While most rival houses accepted no poems that exceeded 40 lines, Rety accepted two Byronic epics by Adrian Brown. Occasionally he published himself: he was best at the short and pithy. He also deviated into prose, but very seldom: most recently, on the publication of my La Sardegna senza Lawrence by Aipsa Edizioni he asked me to translate it into English under the title Sardinia without Lawrence. He deemed it honorary poetry. How adept he was at making mediocrities feel special!

At Torriano he was a benign presence. Sometimes, before the poets began – from the floor in the first half of the evening, and, following the interval, specially invited ones – he would treat us to his feelings on this and that. Diffident-downright, he would tentatively lay down the law, signing himself off with a shrug: 'I don't know.' Occasionally chairs would begin to creak, muttering, 'It's for poetry we're here, so let's get on with it.'

In 1996 Rety jointly published the late A.C. Jacobs' Collected Poems and Selected Translations with Menard Press, whose director, Anthony Rudolf, found him of an anarchic disposition and no slave of the clock, easily distracted from the task in hand – which was to establish the best possible text. They remained firm friends.

During his final decade Rety profited from the practical help of a businessman-poet, David Floyd, who found the collaboration exciting, exasperating, rewarding. "John came up with great ideas and quite bizarre ones. And he had this capacity to conduct three different conversations with you at the same time, often while talking to someone else."

In 2009 an evening at the Barbican was arranged in Rety's honour, but by then his energy and enthusiasm seemed in decline, as if he felt his work were done. By now the grant from Camden Borough Council to pay the rent on Torriano Meeting House had ceased, and he had little stomach for the fight. Closure threatened, but poets rallied round raising money.

John Rety, publisher: born Budapest 8 December 1930; partner to Susan Johns (one daughter); died London 3 February 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks