John Langley: Producer who turned police work into prime reality TV

‘Cops’ became one of the longest-running shows in history before being cancelled following claims it reinforced racial stereotypes

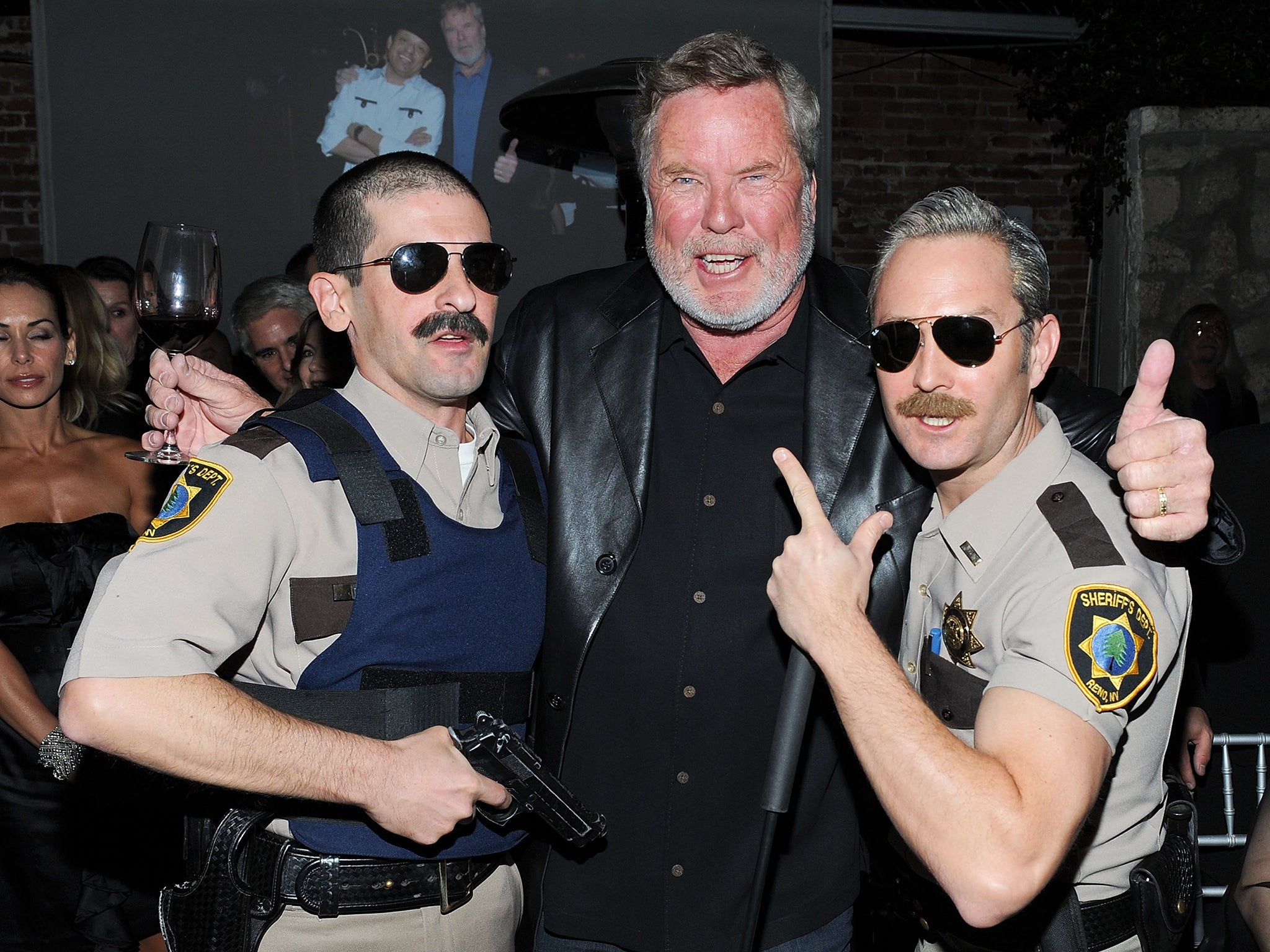

John Langley, who helped pioneer reality television as co-creator and executive producer of Cops, has died aged 78. The show became one of the longest-running in history before being cancelled last year after criticism that it reinforced racial stereotypes and glorified police misconduct.

The cause of Langley’s death was an apparent heart attack, said Pamela Golum, a spokesperson for his production company. Langley, an avid off-roader who drove cars bearing the Cops logo, was racing in the Record Ensenada-San Felipe 250 when he died.

Premiering on Fox in 1989, Cops became a primetime sensation, beguiling millions of viewers each week with its promise of an unvarnished look at law enforcement, without narration, music or re-enactments. Police officers were shown tackling suspected drug dealers, breaking up prostitution rings, evacuating the streets of New Orleans during Mardi Gras, and arresting intoxicated drivers – including one man who forgot he had a marijuana joint tucked behind his ear.

The series became one of the first hits for the fledgling Fox network and was credited with popularising a “video verite” style – in which realism is conveyed through shaky handheld camera footage – that became a staple of such programmes. Its simple formula of shadowing ordinary people at work also served as a model for reality TV. “Where would we be without them?” said Thom Beers, a producer of reality shows including Deadliest Catch and Ice Road Truckers, in a 2012 interview with The Wall Street Journal.

Langley shared four Emmy award nominations for Cops, which he created with producing partner Malcolm Barbour. “No TV series travels as light as Cops, yet delivers such a powerful load,” New Yorker journalist James Wolcott wrote in a review. “As an ongoing sociology lesson, it’s worth a dozen blue-ribbon commissions.” A Boston Globe reviewer wrote that the show “delivers ‘real life’ TV that is as straightforward as a nightstick to the kidneys”.

Some critics argued that Cops promoted racist stereotypes by frequently featuring black and Latino suspects, and that it served as little more than public relations for law enforcement departments, who were allowed to screen footage before it aired. Episodes showed questionable or disturbing police practices, such as a white officer in Wichita using his flashlight to pry open the mouth of a black suspect.

“The dominant image is hammered home again and again: the overwhelmingly white troops of police are the good guys; the bad guys are overwhelmingly black,” New York Times television critic John J O’Connor wrote in 1989, reviewing the pilot, which followed officers in Broward County. “Little is said about the ultimate sources of the drugs, and nothing is mentioned about Florida’s periodic scandals in which the police themselves are found to be trafficking in drugs. This is, pure and simple, tabloid entertainment.”

Langley defended the show as “existential” television, simply capturing reality as it unfolded. A one-time PhD student at the University of California at Irvine, he took a circuitous path to reality TV, dropping out of graduate school shortly before completing his thesis on the philosophy of aesthetics.

He later wrote screenplays, worked as a researcher for Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and promoted movies, before turning to documentary filmmaking, partnering with Barbour to make Cocaine Blues, a 1983 film about the drug trade. “I basically starved doing it, with three children to feed,” he told the Times in 2007.

The movie led to work with ABC News correspondent Geraldo Rivera, who enlisted Langley and Barbour to make a 1986 documentary special, American Vice: The Doping of a Nation. As Langley told it, he and his colleagues “orchestrated and arranged three live drug busts”, persuading law enforcement departments in Houston, San Jose and Broward County to conduct their raids at a particular time and date, and to let a camera crew tag along.

The special served as a prototype for Cops, which Langley said he conceived after riding around with police officers during the making of Cocaine Blues. Following a writers’ strike in 1988, he successfully pitched the series to Fox executive Stephen Chao, who was looking for new projects after creating America’s Most Wanted but was surprised that Langley thought he could make a show using nothing but raw footage.

“My mind was whirling,” Chao recalled in a 2018 interview with The Marshall Project. “I was like, ‘How can you possibly deliver such quality every week, with so much action?’ He shrugged his shoulders. He said, ‘I’m the pizza man. I can deliver every week.’ It was such a stupid thing to say. I laughed, of course. None of us knew it was possible.”

Over 32 seasons and 1,064 episodes, Cops remained largely unchanged, opening with the reggae strains of a song by Inner Circle: “Bad boys, bad boys / Whatcha gonna do? Whatcha gonna do when they come for you?” The show expanded beyond the US to follow officers in Britain, Hong Kong and the Soviet Union, and Langley continued serving as executive producer after Barbour retired in 1994.

Cops also faced persistent criticism, with the civil rights group Colour of Change launching a campaign in 2013 urging Fox not to renew the show. The organisation argued that the series’ producers and advertisers had profited from “distorted and dehumanising portrayals of black Americans and the criminal justice system”.

Fox dropped the show later that year, and it was soon picked up by Spike TV, now known as the Paramount Network. The show was cancelled after 32 seasons last June, amid widespread protests against racism and police brutality sparked by the murder of George Floyd.

By then, Cops was drawing about half a million viewers per episode, according to Nielsen data, down from more than 8 million at its peak in the 1990s.

“You can be entertained by it, you can be disgusted, but it is what happened,” Langley told the Times, comparing the series with some of the reality shows that followed in its wake. “It wasn’t staged, it wasn’t scripted. I didn’t put anyone on an island and tell them what to do.”

John Russell Langley was born in Oklahoma City on 1 June 1943, and grew up in the Manhattan Beach area of Los Angeles.

He served in an army intelligence unit in Panama, according to his production company’s website, and studied English at California State College at Dominguez Hills, receiving a bachelor’s degree in 1970 and a master’s degree in 1971.

Early in his television career, he produced investigative specials on terrorism and the John Kennedy assassination, both hosted by newspaper columnist and reporter Jack Anderson. Langley later worked with his son Morgan, a fellow producer, on reality shows including Vegas Strip and Jail.

In addition to his television credits, Langley was a producer of the 2009 crime movie Brooklyn’s Finest, directed by Antoine Fuqua, and started a winery in Argentina.

Survivors include his wife of 49 years, Maggie (nee Fox); a daughter from an earlier marriage; three children from his second marriage; and seven grandchildren.

Langley said he developed a standard three-act structure for each episode of Cops. An opening “action” segment, usually involving a chase sequence; then came a “lyrical” segment, which often ended with a perp or family member in tears; and lastly a “think piece”, intended to get viewers to reflect on what they’d witnessed.

“Usually that’s about the drug laws or things of that nature that maybe people will think about and go, ‘Wait a minute. Why do we keep arresting these people over and over again who are users? Why don’t we just send them to rehab and stop that problem and decriminalise it?’” he told Cigar Aficionado.

His views on crime shifted, he said, as he watched drug offenders who were frequently sent to prison rather than rehab. “What makes Cops run? Drugs, drugs, drugs,” he told the Times. “What’s wrong with society? Drugs, drugs, drugs.”

John Langley, TV producer, born 1 June 1943, died 26 June 2021

©The Washington Post