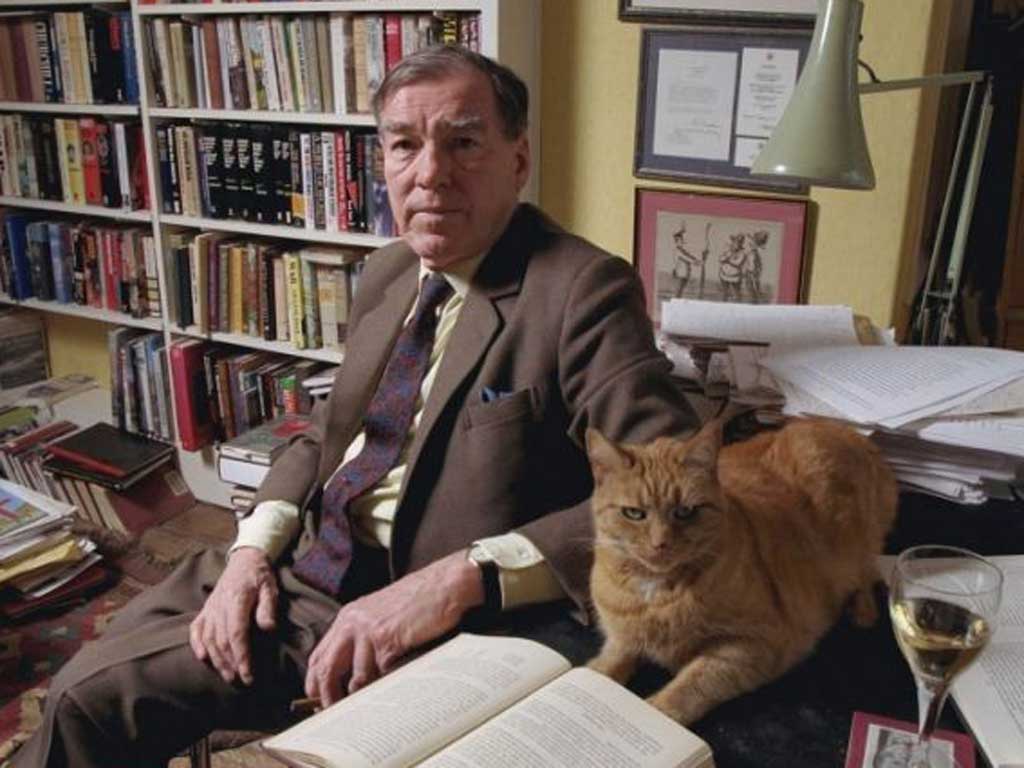

John Keegan: Historian hailed as the foremost authority of his generation on warfare

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.John Keegan did not emerge as the greatest living authority of military warfare by chance. As good generals do, he managed the circumstances of his life, both good and bad, with consummate skill and not a little courage. He described his unique method of approaching battle encounters as "the order": "You need an exact list… for instance at Waterloo …how many French units, how many British and Allied… who commanded them, their position in the field, the terrain itself, how that affected combatants on either side." Just as a businessman must look to his accounts, he would explain, you may not tell the story of battle, you have no account, until you account for all the details. Then you have the bill right.

To account for Keegan's own remarkable life, therefore, the list is as follows. He was of Irish descent, his Catholic faith his mainstay in life. And this he needed. Brought down as a boy with tuberculosis of the hip, he spent long months away from his schooling in a hospital bed. An avid reader, he plundered the library and returned to his studies far more enriched than his peers. Educated first at King's Taunton and latterly by the Jesuits at Wimbledon College, John had the good fortune to fall under the spell of, "Dicky" Milward, a lay master whose enthusiasm for history was legendary. From then on, history was his field of conquest. But the seeds of military interest had been sown when his father, a veteran of the First World War but by then a London schools inspector, had charge of the evacuation of some 300 schoolchildren to Taunton. Here the young and curious boy witnessed the massive build-up to D-Day and spent hours plane-spotting. Unable to compete on the rugby field, Keegan's notable contribution to public life at the College was a rendition of GK Chesterton's epic poem Lepanto given to the school at the school prize-giving. The celebration of Don John of Austria's famous sea battle that turned the tide of the Muslim invasion of Europe – 143 iambic pentameters passionately proclaimed – foreshadowed all that was to come. He easily won his place to Oxford's blue ribbon Balliol College where he was tutored by Richard Southern and, challengingly, by the Marxist Christopher Hill. Between Scylla and Charybdis, he chose for his special subject "Military History and the Theory of War".

Coming down from Oxford, he worked for two years in the American Embassy before landing a post as history lecturer at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, where he spent the next 26 years. He enjoyed his lecturing, his proximity to emerging young officers, the military ethos of discipline – above all honour. Sandhurst, moreover, gave him space to think and to write.

Keegan had always written since childhood: he was also a fluent conversationalist and the two talents combined with fascination for his subject to yield numerous original and authoritative books. He broke on to the publishing scene with panache. His critically acclaimed The Face of Battle (1976) took three classic military encounters – the battles of Agincourt, Waterloo and the first day of The Somme. Examining in fastidious detail his "order of battle", as he dubbed it, Keegan assembled an entirely fresh account of the nature of warfare. Above all, he placed far less importance on generals than upon the men facing and fighting each other. "The most important emotion in war is fear," he would stress.

Fuelled by his Sandhurst lectures and with hungry publishers in London and New York, he produced a stream of meticulously researched titles. World Armies (1978) was followed by Six Armies in Normandy (1982); the latter following his favourite insight, he examined the signature behaviour of the varied nation armies pushing on from the D-Day landings. Next came The Mask of Command; it dealt with four warring leaders – Alexander the Great, Wellington, US Grant and Hitler – complementing his military classic, The Face of Battle.

Keegan took his family to their new home, a 17th century manor house in Kilmington, outside Warminster. He dedicated this latest book to his wife, Susanne, herself an accomplished writer with two biographies of Alma Mahler. In 1989, he embarked on his most ambitious tome to date, editing The Times Atlas of the Second World War. Its scope was far-reaching, recording in meticulous detail all major battles of the Second World War.

Awards began to arrive: his History of Warfare (1993), the Duff Cooper Prize, The First World War, the Westminster Medal – and it sold 200,000 copies in the US alone. In 1986, a chance conversation with his friend Max Hastings, who had just been appointed editor of the Daily Telegraph, led to a career change, and Keegan became Defence Correspondent. His sub-editor describes how docile John was as he learned the disciplines of news reporting – no longer the eloquent and leisurely style of his published triumphs. His new readership needed crisp copy, with the pith of the story in the first two lines. Keegan gladly settled in.

In the Millennium Honours list, Keegan became Sir John, a title he wore shyly. "In my village, they all still call me just John". In 2009 came a further major work: The American Civil War was a critical success, praised for his treatment of the complexities of a nation torn apart by "the first industrial war", his conclusion being that scars still linger to the present day.

His ties with the US were numerous. He was Visiting Fellow of Princetown in 1984, Delmas Visiting Professor of History at Vassar College 1997-98. His advice was sought by President Bill Clinton ahead of his visit to Normandy to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the D-Day landings. "I told him, don't forget the Canadians, and above all the Poles – they played a crucial part…" He served as a Commissioner of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and gave the BBC Reith Lectures, published in 1998 as War and our World.

John Desmond Patrick Keegan, military historian: born 15 May 1934; OBE 1991, Kt 2000; married 1960 Susanne Everett (two sons, two daughters); died Kilmington 2 August, 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments