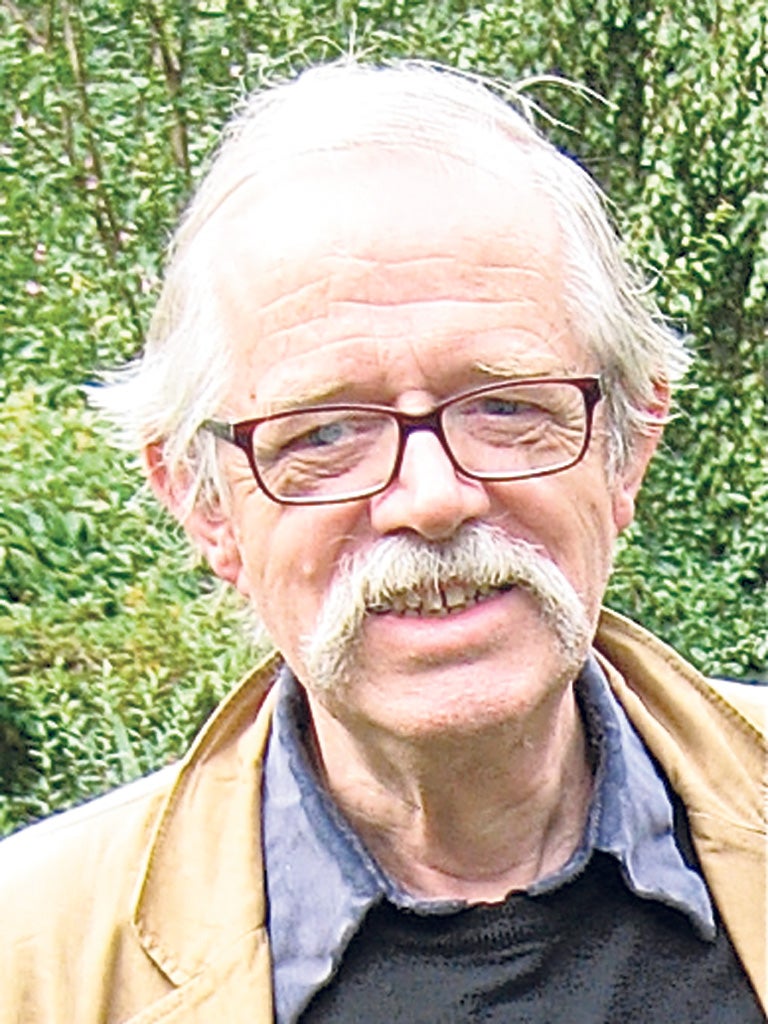

John Gage: Art historian who established himself as anunrivalled scholar of Turner

The art history world has suffered a grievous loss in the person of John Gage, who has died at the age of 73. A scholar of immense range and erudition, he will beremembered chiefly for his ground-breaking contributions to the study of JMW Turner and to the history of colour. His 1987 monograph, JMW Turner: A Wonderful Range of Mind, stands out as much the finest account of the artist and of the visual and intellectual interests that shaped his work. Colour and Culture: Practice and Meaning fromAntiquity to Abstraction (1993), the fruit of more than 30 years' research andreflection, established him unquestionably as the pre-eminent historian of artistic uses and theories of colour in western cultures. Translated into five languages, the book is the standard reference source on the subject andhas found a wide readership outside academia. In 1994 it received theprestigious Mitchell Prize for the History of Art.

After attending Rye Grammar School, Gage studied modern history at Oxford, graduating in 1960 with a third-class degree – so often the mark of an independent mind in those days. Periods as an English tutor in Italy and Germany in his early twenties helped develop the language skills that facilitated his entry into art history.

In the early 1960s he supported himself through a range of jobs while writing a thesis on Turner at the Courtauld Institute under Michael Kitson's supervision. Completed in 1967, this was the basis for his second book, Colour in Turner: Poetry and Truth (1969), which bucked the current trend to treat the artist as a proto-modernist and stressed that colour in his work was never separate from considerations of meaning. While not entirely alone in taking Turner seriously as an intellectual (Jack Lindsay had also made important steps in this direction) Gage went far deeper than others in his close-grained analysis of the intellectual world in which the artist's preoccupations were formed and in approaching him from a European perspective. There was simply nothing that rivalled it in the literature of British art at the time.

Gage taught at the newly formed School of Fine Arts and Music at the University of East Anglia from 1967-79; when I arrived in Norwich as an MA student in 1972, he told me that EH Gombrich was the only contemporary art historian asking the kind of questions that interested him – although Ruthven Todd's maverick study of Romantic art and science, Tracks in the Snow, was another reference point. It was Gombrich's Art and Illusion that provided the conceptual frame for John's seminal exhibition "A Decade of English Naturalism, 1810-1820" (Norwich Castle Museum, 1969), which helped set the agenda for the efflorescence of British landscape studies in the following two decades. However, while Gage shared with Gombrich an abiding concern with connections between art and the natural sciences, he did not share his combative Popperian stance on theory or his aversion to modern art, about the colouristic aspects of which he wrote extensively.

In 1979 Gage moved to Cambridge University, where he taught until taking early retirement in 2000. He was made Reader in the History of Western Art in 1995, the same year he became a Fellow of the British Academy. In addition to a steady output of articles and catalogue essays, Gage's years at Cambridge were marked by the publication of a string of books, which in addition to the Turner monograph and Colour and Culture, included an edition of Turner's correspondence (1980), an anthology of Goethe's writings on art (1980), and a further selection of colour essays titled Colour and Meaning: Art, Science, and Symbolism (1999).

In 1981 he and Penelope Kenrick – whom he had married three years before – had a daughter, Charlotte. After his retirement John moved to an old farmhouse in Tuscany. He had always had a fondness for rural life and rented the hall farmhouse at Mannington in Norfolk for many years. He now also began to spend a lot of time in Australia, where he became fascinated by Aboriginal art, about which he left an unfinished monograph.

Gage was unpersuaded by much in the theory wave that swamped the discipline of art history from the 1970s onwards. He particularly disliked scholarship driven by some fashionable theoretical nostrum that showed no interest in the complexities of the artwork or of the web of historical circumstances from which it emerged. However, beyond making some tart asides in his writings he did not publicly oppose the new trends. Since he had always seen his own work as interdisciplinary – and he argued that the study of colour was necessarily an anthropological matter in part – he was not much impressed by the use of "interdisciplinarity" as a club with which to beat establishment practices in the field.

He belonged to a generation of scholars that saw a wide span of historical knowledge and engagement with foreign-language cultures as essential to art history's standing as a science (in the Germanic sense). This does not mean that his own work was innocent of theory, and its range of philosophical and scientific references is impressive. But in the face of what he called art history's new-found "nervousness about method", he cleaved to a kind of inspired empiricism, insisting that methods were only tools.

Gage's work, though, was more than just his publications and contributions to scholarly conferences. As a teacher he set a daunting example of enormous learning, but his presentation was always lucid and seasoned with flashes of dry wit. He had a puckish sense of humour and could scarcely resist the occasion for a pun. To me and the many other graduate students who worked with him – and who sometimes deviated from the model he offered – he showed great warmth and personal generosity. He was and remains an unforgettable example of independent thought and scholarly integrity.

John Gage, art historian: born Bromley, Kent 28 June 1938; married 1978 Penelope Kenrick (divorced 2002; one daughter); died Cambridge 10 February 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks