John Arden: Playwright whose political ideas infused his epic, eloquent and flamboyant work

It might be said of the two outstanding British playwrights who were born in 1930 that both had great talents, one for the epic and the other for a theatre of contained limitation, and that the latter developed that talent to its maximum extent, while the former allowed his to diminish.

I refer to Harold Pinter, basically a minimalist, whose claustrophobic plays, mostly set in dowdy sitting rooms, investigate the limitations of life with microscopic intensity, and his artistic opposite John Arden, who has died at the age of 81.

Arden is the nearest Britain has produced to a Berthold Brecht (even considering Edward Bond and Howard Barker) and the range of his talent was enormous. He thought on a large canvas so that even when his plays are produced in small intimate theatres they gave the impression of size and space, belonging as much to the outdoors as Pinter to the indoors. Arden had the same virtues and failings as Brecht, writing out of a passionate desire to educate and make his audiences think, while sacrificing style and his own artistic integrity where he saw a possibility of increasing the weight of his message.

Born in Barnsley and educated at King's College, Cambridge, and Edinburgh School of Art, where he studied architecture – which he practiced only briefly but which remained a hobby throughout his life – there was always something of the 18th century aristocrat about Arden, in the precision of his everyday language, the breadth of his interests and opinions and the arrogance which enabled him to do what he wanted against advice and opposition. I doubt if he ever believed himself to be wrong, either about work or the decisions he took on other matters. One could not tell from his voice whether he was the son of a duke or a miner.

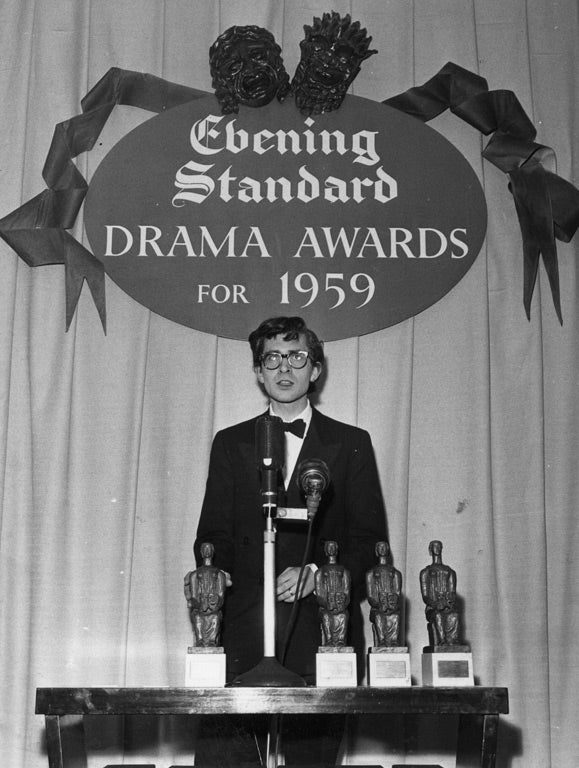

He first attracted attention with a prize-winning radio play The Life of Man and with his second stage play Live Like Pigs (1957) which depicted the squalor of the underside of society so realistically that it invoked an outcry. This was followed by his masterpiece, Serjeant Musgrave's Dance, whose protagonist is a soldier returning from the Crimean War preaching pacifism and revolution. It is extremely violent, with much action, great eloquence and a flamboyance found in no other British dramatist: it would have greatly appealed to Artaud, who was almost unknown in Britain at the time, fitting very well into his concept of "total theatre".

Arden found his inspiration in the yeoman class of rural Britain from which army recruitment had largely come, a class accustomed to suffering and injustice, capable of great endurance and courage, but with a burning anger as well as a stoicism in its belly; the anger has been there for generations; indeed it may go back to Norman times.

Arden's work was not only based on a mythology – the British equivalent of Rousseau's noble savage – but became its own mythology, so that one always sees echoes of long-buried wrongs in his plays, which have an epic character and an antrean feeling of horror. Arden attacks both the minds and the nerve-endings of his audiences. Like Brecht, he used songs, ballads and interruptions to get his message over, and from the time of his collaborations in the theatre with his wife Margaretta D'Arcy, there was greater use of such diversions, often improvisations of less than professional competence, bad music and toleration of silliness.

This was a pity because the major plays are magnificent achievements, expressionistically portrayed history that can greatly excite an audience, with dramatic speech of much poetic intensity. There can be no doubt of Arden's great talent, but he constantly diminished it with touches that came from his wife, whose dramatic talents were different and seemed to influence him away from his natural style, which is poetic, expressionistic, intellectual total theatre in a similar vein to the productions of Reinhardt, Piscator, Brecht and Barrault. His natural producer would have been Peter Brook, were Brook not so in conflict with the spoken word, always humbled by him for the effect of dramatic spectacle.

After Sergeant Musgrave, which was successful all over Europe and finally even in Britain after a bad start, came The Workhouse Donkey, one of the first attacks on that element in the Labour Party which became more interested in the trappings and patronage of power than in advancing socialism. To a certain extent it might be said to have anticipated the Poulson scandal, which revealed the extent of corruption in the North-east of England in Labour-dominated local government authorities.

His next play was one of his finest and it never had the success it deserved: audiences have always been slow to follow the reviewers where Arden was concerned. Armstrong's Last Goodnight was based on a Scottish border ballad and the historical event behind it. Premiered in Glasgow in 1964, it proved how well Arden could cope with Scottish dialect, but this was toned down for London. His hero is, once again, a rebel against authority, in this case the Scottish crown, and he ends up on the end of a rope, like Musgrave.

The following year Left Handed Liberty, commissioned by the City of London for the 750th anniversary of Magna Carta, was presented at the Mermaid Theatre: it was his most Brechtian play, similar to Galileo Galilei in its historical approach. Thereafter there was a definite decline in credibility; not that his plays became in any way uninteresting, but the sure hand of theatrical genius and never-slackening tension was less apparent.

In The Island of the Mighty (1972) he exploited his gift for myth-making, drawing on the old Irish, Welsh and Arthurian legends and connecting them for his own dramatic ends; it rampages through history with incidents borrowed from many local legends, especially The Golden Bough, with abandon but with fascinating effect. On the opening night Arden and his wife picketed the play, asking the audience not to see it, because David Jones, the director, had, he claimed, distorted it. But Arden was enthusiastically present at all the rehearsals until his wife returned from Ireland shortly before the opening, and only then did he complain about Jones' direction. The reviews were mixed.

The truth is that there were two sides to Arden's character. On his own he was an intense, politically conscious, intellectual craftsman, a poet with a big vision, great command of language and an ability to create history that was not real history but a Jungian chronicle of ancestral memories that could, because art displaced fact, be much more effective in creating the kind of history that people feel rather than learn when world events overtake them and their lives become caught up in civil wars, revolutions or plagues. A potent myth-maker at his best, he betrayed his own talents increasingly from the late '60s onward, when the other side of his character became more prominent.

This other side was closely bound up with his wife, an Irishwoman with strong gypsy traits, for whom discipline, order, even the most elementary safety measures in life, were anathema. It wasundoubtedly a close and happyrelationship: but she seemed to suck the discipline from his creativity, while he took his moral and physical strength from her. She was creative on herown account – they wrote much together – but in a different direction from him, and the mix did not succeed artistically. This was evident in his least happy play, an opera of sorts, The Hero Rises Up (1968) where the subject was the relationship between Lady Hamilton and Nelson, which he directed himself, and which fell below an adequate professional level.

Politically Arden and Margaretta D'Arcy were as one. She involved him in Irish causes, especially the Civil Rights movement and republicanism, but his natural bent would have been no different. As an historical playwright he had much in common with Robert Bolt, but never achieved the latter's commercial success, and their approach was very different: Bolt simulated reality, Arden created myth.

Arden had little in common with his close contemporaries who came to prominence at the same time, John Osborne and Arnold Wesker, although for a time they were ideologically close. David Rudkin came nearer to him in atmosphere, Edward Bond in integrity of feeling – and taste for dramatic violence. Arden has sometimes been relegated, mistakenly in my view, with the absurdists; he occasionally shares their feeling for surrealism; but it goes no further than that.

At bottom John Arden was an intuitive political poet, who realised the cultural relationship between the oppressed and their oppressors and its effect on character. Had he been American he would have written of the black experience.

He understood the political role of the theatre as few others have done in Britain, and it was his misfortune to work in a country where a talent like his had so few outlets. It was disheartening to witness one occasion when this born educator tried to introduce art and culture to a small village, Kirbymoorside in Yorkshire. He rented a cottage for the summer, and spent much time filming everday life, especially recording how the old saw the young and young saw the old.

At the end of the summer the Ardens put on at their own expense a festival: lectures, folk singers, dancers, readings and sometimes performances of plays, classical music, discussions and frequent showings of the film. Everything was free and everyone was invited, but some, too shy to enter the cottage, about which there were many suspicions in some quarters, would only gather at the windows to watch the events or see themselves on the screen. It shook the whole village up, but when the Ardens went away life returned to its normal slow rhythms and the excitement was quickly forgotten.

After 1970 politics of a mainly radical and nonconformist-anarchist bent, allied to many causes but not party-orientated, preoccupied the Ardens, and they went to live in Galway. Their joint plays – by now Arden wrote only in collaboration with his wife – were mainly performed in small theatres, and he turned to writing for radio and lecturing. He also explored moral themes that had always interested him in two novels, Silence Among the Weapons (1982) and The Book of Bale (1988). His interest in Ireland led to a series of improvisational performance-art plays with the general title The Non-Stop Connolly Show. He also wrote plays for children and an adaptation of Goethe's Gotz von Berlintingen under the title Ironside (1963) and there are other writings, including books of essays.

In spite of his refusal to follow the career of a major national playwright, as his beginnings suggested he would, Arden always remained true to a very personal anti-establishment ethical code, and was a moralist primarily, with an understanding of the power of corruption in nearly every society, past and present. He simply distanced himself from the social position that goes with success, and if he disappointed his admirers it was unconsciously done, not because of any failure in his powers. In his outlook he came to resemble Samuel Beckett in many respects, although stylistically they are poles apart.

He was an attractive man with anintensity of manner that sometimes seemed to border on the fanatical; one could see him as a political revolutionary or a fundamentalist preacher, and perhaps he saw himself as both.His interest in religion was moral and philosophical and although nominally Church of England, it is doubtfulthat he held any firm beliefs. His major plays, up to The Island of the Mighty, assure him an important place in theatrical history.

John Arden, novelist and playwright: born Barnsley 26 October 1930; married 1957 Margaretta D'Arcy (four sons, and one son deceased); died 28 March 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks