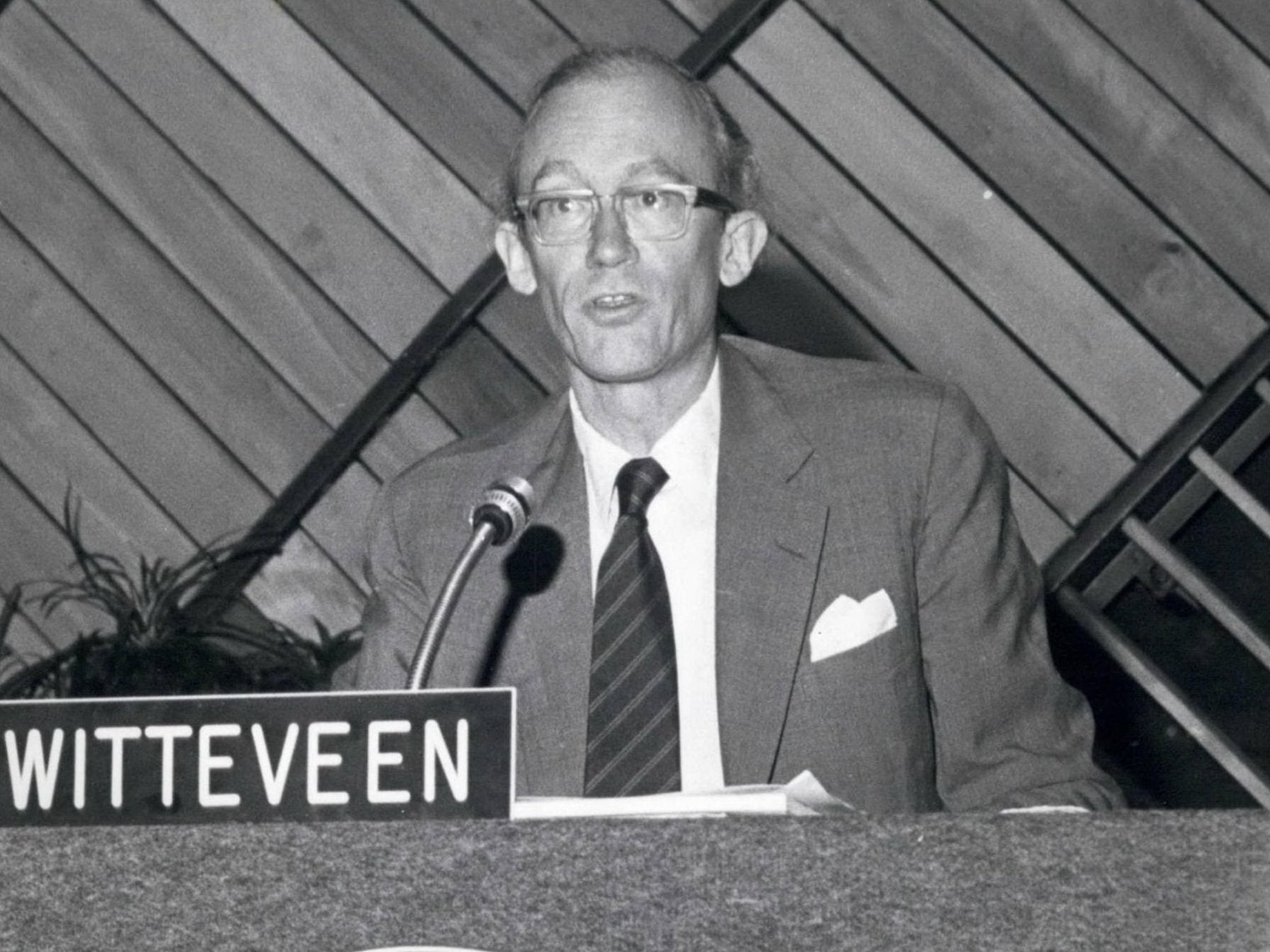

Johannes Witteveen: Economist who bailed out Britain and made the IMF relevant

The former deputy prime minister of the Netherlands navigated financial turbulence and split Britain’s Labour cabinet in the process

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Johannes Witteveen, a Dutch economist and politician who navigated a whirlwind of financial turbulence as the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from 1973 to 1978, all while enlarging the fund’s role as a lender and manager of the global economy, has died aged 97.

Dr Witteveen (pronounced VIT-uh-vane) was a longtime practitioner and leader of Universal Sufism, a religious philosophy rooted in Islam, and was known by fellow Sufis as Murshid Karimbakhsh Witteveen. His death was announced by the International Sufi Movement, which is headquartered in the Netherlands.

Dour and ascetic, with a reputation as a soft-spoken consensus-builder, Witteveen arrived at the IMF during a period in which some economists questioned its very existence. The fund had been established in large part to manage the world’s system of fixed currency exchange rates. But that financial order collapsed after the United States floated the dollar in 1971, and the IMF seemed to become an organisation without a mission.

In the aftermath of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, oil prices exploded, eventually quadrupling – exacerbating a period of global recession and inflation dubbed “stagflation”. For the first time since the Great Depression, each of the world’s major economies was in a recession at the same time.

As managing director of the IMF, Witteveen helped quiet the waters, engineering an $8bn relief measure in which oil-producing nations “recycled” revenue to poorer countries, in the form of IMF loans used to buy oil, address payment imbalances and prop up world trade. Countries were instructed to adopt belt-tightening “adjustment” measures in exchange for the loans.

“What Witteveen did was bring [the IMF] back to being relevant, in a world in which poor countries that didn’t export oil were extremely vulnerable,” said Harold James, a financial historian at Princeton University. “He reoriented the fund from thinking about a world in which there were fixed exchange rates, and where the bigger countries needed policing, to a world in which capital is moving and creating instability.”

Witteveen negotiated the loan packages himself, drawing on his political experience in the Netherlands. A member of the socially liberal, pro-business People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, he was elected to both houses of his country’s legislature, served two stints as minister of finance and was deputy prime minister from 1967 to 1971, under Piet de Jong.

Describing his Dutch political career, The Observer once called him a “velvet fist in an iron glove”.

At the IMF, Witteveen stood firm against the Nixon and Ford administrations, which urged him to denounce Opec after some members of the organisation of oil-producing states issued an embargo against nations that supported Israel during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. That aside, Witteveen was generally credited with repairing the relationship between the US and the IMF, where his predecessor, Pierre-Paul Schweitzer, had battled with the Nixon administration over floating the dollar.

Witteveen, compromising between nations that favoured fixed rate and floating currency exchanges, negotiated an arrangement in which the fund could exercise “firm surveillance” over the exchange rate policies of its member countries.

In 1976 he signed off on a then-record $3.9bn emergency loan to Britain, when the pound had lost much of its value and inflation had risen above 25 per cent. The bailout helped stabilise the country’s finances and was part of a wave of loan packages that dramatically increased the fund’s role as an international lender.

According to The New York Times, member countries were borrowing less than $1bn from the fund in 1973 when Witteveen took office; four years later, borrowing topped $7bn. In his final year as managing director, Witteveen collected $10bn from the fund’s wealthy members to create a new loan programme, dubbed the Witteveen Facility, for needy countries.

Upon his retirement, The Economist magazine likened the IMF to a phoenix, saying it had “risen from the ashes of fixed exchange rates and quadrupled oil prices, with its claim intact to be the overseer of those parts of the world’s monetary system that the world allows it to oversee”.

“Over the next five years, under Mr Jacques de Larosiere, the IMF’s path will be strewn with familiar rocks,” the magazine continued, referring to Witteveen’s successor. “Mr Witteveen has done much to chart the best routes round them.”

Hendrikus Johannes Witteveen was born in the town of Zeist, in central Netherlands, on 12 June 1921. His father was an urban planner, and his grandfather was a socialist senator.

What Witteveen did was bring [the IMF] back to being relevant, in a world in which poor countries that didn’t export oil were extremely vulnerable

Witteveen studied at the Netherlands School of Economics (now Erasmus University Rotterdam) under Jan Tinbergen, who was later awarded the first Nobel Prize in economics. He received a doctorate in 1947 and worked as a government economist and a professor at his alma mater, launching his political career when he entered the Senate in 1958.

Although many of Witteveen’s supporters assumed he would run for a second term as IMF managing director, he chose instead to retire, citing personal reasons that included the illness of one of his children.

He went on to become the first chair of the Group of Thirty, a Washington-based nonprofit organisation that researches international economic and monetary affairs, and also served on the boards of companies including Royal Dutch Petroleum and the asset management firm Robeco.

Witteveen’s wife, Liesbeth de Vries Feijens, an oncology professor, died in 2006. They had four children, including Willem Witteveen, a Dutch politician who died in 2014 aboard Malaysia Airlines Flight 17. The plane was shot down over eastern Ukraine amid conflict between the government in Kiev and Russian-backed separatists; a Dutch inquiry later concluded the aircraft was downed by a missile that came from the Russian military.

Witteveen was co-president of the International Sufi Movement, a Sufi organisation that espouses universal harmony – the sort of peaceful coexistence of nations and people Witteveen sought through his work at the IMF. Often, even at the height of his career, he seemed more interested in discussing the mysteries of the human soul than the intricacies of global finance.

“Western man has directed himself too much toward the external,” he said, according to a 1973 profile in The Times. “Too many fear the internal life. The mystical world is the most beautiful experience. It is a pure gift of God.”

Johannes Witteveen, economist and IMF chief, born 12 June 1921, died 23 April 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments