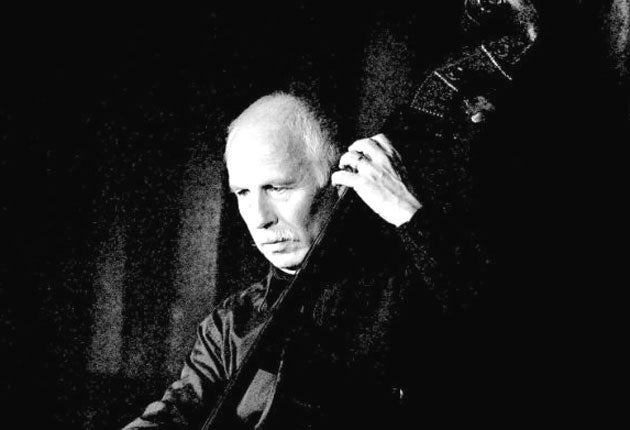

Jeff Clyne: Bassist and stalwart of the British jazz scene for 40 years

For four decades, Jeff Clyne led the way as the most accomplished and versatile of British bass players.

Some would claim that, despite its grandiose title, the apex of British big band jazz was Tubby Hayes' 1966 recording 100% Proof. Clyne had been renowned among musicians and jazz club audiences since he joined the Jazz Couriers in 1958, but it was his work throughout the Hayes album and his imaginative bass soloing on the Miles Davis tune "Milestones" that introduced a large swathe of the world's jazz fans to the accomplishments of his work.

In his listings in a booker's guide to available musicians, Clyne described himself as playing "Contemporary, Bebop, Fusion, Free/Improvised and Mainstream", thus covering just about all the posts outside of banjo-driven jazz. But it was no idle claim, for he was able to express himself with eloquence in any style and was much sought after by any bandleader who found him available, being soon corralled as a regular by Tubby Hayes and Ronnie Scott after his arrival on the scene in the late Fifties. It was appropriate that he appeared at Ronnie Scott's on its opening night in November 1959, when the advertised attractions included Hayes, Scott and "the first appearance in a jazz club since the relief of Mafeking by Jack Parnell".

After a brief flirtation with the tenor saxophone, Clyne took up bass-playing when he was 17 and reached such a high standard so quickly that he was able to join The Third Hussars Band the next year for his National Service. Released from the army in 1957 he worked with Tony Crombie's Rockets and formed an early association with the pianist Stan Tracey before working for three months on the Atlantic liner Mauretania.

In late 1958 he joined the Jazz Couriers, a hard bop quintet co-led by Scott and Hayes that was intended as a British parallel to Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers, and stayed until May the next year. After a tour of US Army bases in France with the tenor saxophonist Bobby Wellins, he returned to England and joined the clarinettist Vic Ash's Quartet in September of that year. From there, he joined the Tubby Hayes Quartet, where he stayed until 1961.

He played often with Hayes in the succeeding years, and was already probing into free improvisation, one of the more daunting and less popular forms of the music. Clyne was, until the end of his life, to keep abreast of new developments in jazz and was often seen at concerts and recitals checking on the work of new musicians emerging on to the jazz scene.

In 1965 he was with Bobby Wellins in the Stan Tracey Quartet which recorded Tracey's remarkable Under Milk Wood suite. The album remains a classic among jazz performances and it was no surprise when in 1966, after spells with various small groups, Clyne became a house musician at Ronnie Scott's, where Stan Tracey was the resident pianist.

From then on, Clyne backed and was respected by leading American musicians such as Zoot Sims and Ben Webster and accompanied a legion of singers such as Annie Ross, Marian Montgomery and Norma Winstone.

Clyne travelled to the US to study music from October 1966 to February 1967 and by now was playing with avant-garde musicians in the Spontaneous Music Ensemble and Trevor Watts' Amalgam. He was also a member of many piano trios in the late Sixties, notably those of Dudley Moore and Gordon Beck. His role in the Don Rendell-Ian Carr Quintet in 1968 led to him joining Ian Carr's Nucleus, a mightily successful fusion band that won an award at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1970 and with which Clyne played until 1971.

Always in demand, he played over the next few years with Alan Skidmore's Quartet, Bob Downes' Open Music, the London Jazz Composers' Orchestra, and his own band, Turning Point, co-led with the singer Pepi Lemer, for which he composed much of the music. Turning Point recorded two distinguished albums, Creatures of the Night (1977) and Silent Promise (1978). Another outstanding album under his name was Twice Upon a Time, recorded in 1987 with the guitarist Phil Lee.

As important as his appearances in all these bands was his work in music education. He was a co-director of the Wavendon summer jazz course and taught at the Guildhall School of Music and at the Royal Academy of Music.

He played jazz gigs until the end of his life and despite his fame and achievements, Clyne remained a modest man. On his death, the internet was flooded with messages from his grateful students, who he also regarded as friends.

Steve Voce

Jeffrey Ovid Clyne, bass player and music teacher: born London 29 January 1937; married (two sons, one daughter); died London 16 November 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks