Jean-Luc Godard: Master of French cinema who pushed boundaries

At his best, the Franco-Swiss film director and Young Turk of the New Wave was responsible for some of the most sublime moments of 1960s screen time

Jean-Luc Godard, the European filmmaker and cinematic rule-breaker regarded as one of the most influential, uncompromising and at times befuddling artists of his era, has died aged 91.

Over six decades, Godard’s output of more than 90 features, documentaries, shorts and videos defined him as one of the most productive, mischievous, didactic, subversive and polarising of moviemakers.

Starting with his 1960 debut feature, Breathless, Godard rode the crest of what became known as the New Wave, a group of young film critics – including François Truffaut, Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol – who took up directing to liberate what they regarded as a calcified movie industry. “We barged into cinema like cavemen into the Versailles of Louis XIV,” Godard said.

Many critics have come to see Breathless as a galvanising work of art, shunning linear narrative and anything smacking of convention. Godard used jump cuts to unsettle; the editing technique, which cuts a frame or two from a scene, is now common in film and music video but was startling in the early 1960s.

These techniques and motifs set a template for much of his later work, with characters who stepped out of character to wink, wave and mug at the camera. His films skewered sex, war, religion and commercialism with ironic juxtaposition of image and dialogue, and he overstuffed them with witty and self-conscious allusions to literature, old movies and radical-left politics.

The American critic Susan Sontag hailed Godard in 1968 as one of “the great culture heroes of our time,” putting him alongside Pablo Picasso, James Joyce and Igor Stravinsky as revolutionising their respective fields of art. Godard’s unpredictable iconoclasm appealed to Sontag, who noted his “prodigal energies, his evident risk-taking, the quirky individualism”. It wasn’t that he was steadily brilliant, she wrote, but that he was brimming with ideas and seldom repeated himself.

Sontag wrote that Godard helped create a new language of cinema with movies that were “both achieved and chaotic, ‘work in progress’ which resists easy admiration”. Yet his enthusiasts were wide-ranging. He also had an incalculable impact on international art-house cinema.

At his best, Godard was responsible for some of the most sublime moments of 1960s screen time, including the comical and barbaric car pile-up in Weekend (1967) as a lashing at greed and materialism; the cocktail party in Pierrot Le Fou (1965) where bourgeois guests mouth the scripts of television commercials; and the impromptu pop-music dance by a trio of crooks in 1964’s Bande à part (Band of Outsiders).

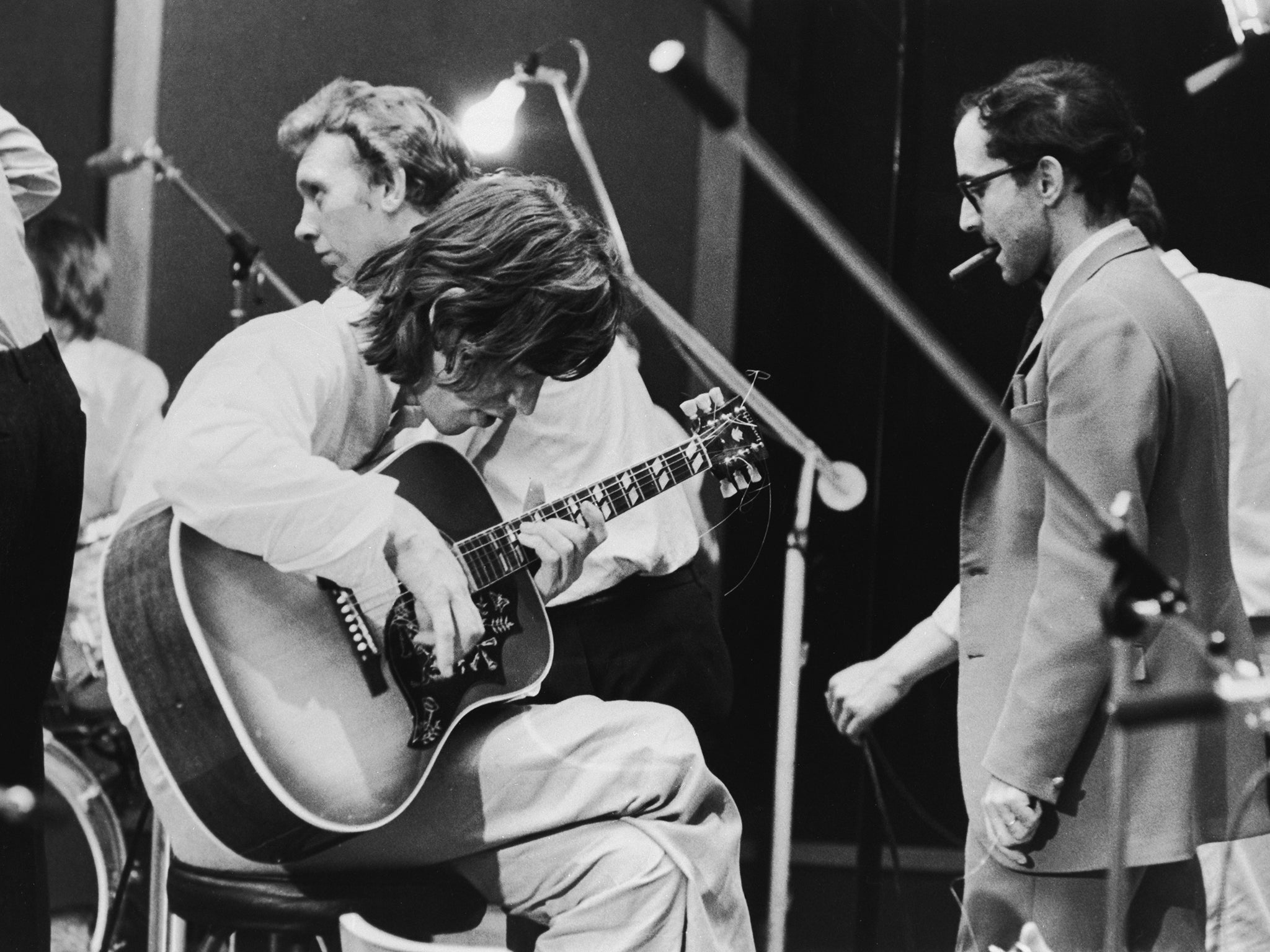

Where a playfulness and exuberance pervaded his early films, Godard gradually became more politically dogmatic. His feature Sympathy for the Devil, filmed in 1968 and released in 1970, alternates scenes of Black Power revolutionaries and Maoist agitprop with lengthy shots of The Rolling Stones recording the title song. Critics dubbed it nearly unwatchable.

In later years, changes in public taste and his challenging, ceaselessly provocative style limited his audience to serious film buffs and connoisseurs, but the impact of his early work on generations of moviemakers cannot be overstated.

Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1996) has all the traits of a Godard film, with its fanciful plot, two-dimensional characters and tributes to pop culture; the dance scene with John Travolta and Uma Thurman has been described as an homage to the dance sequence in Bande à part.

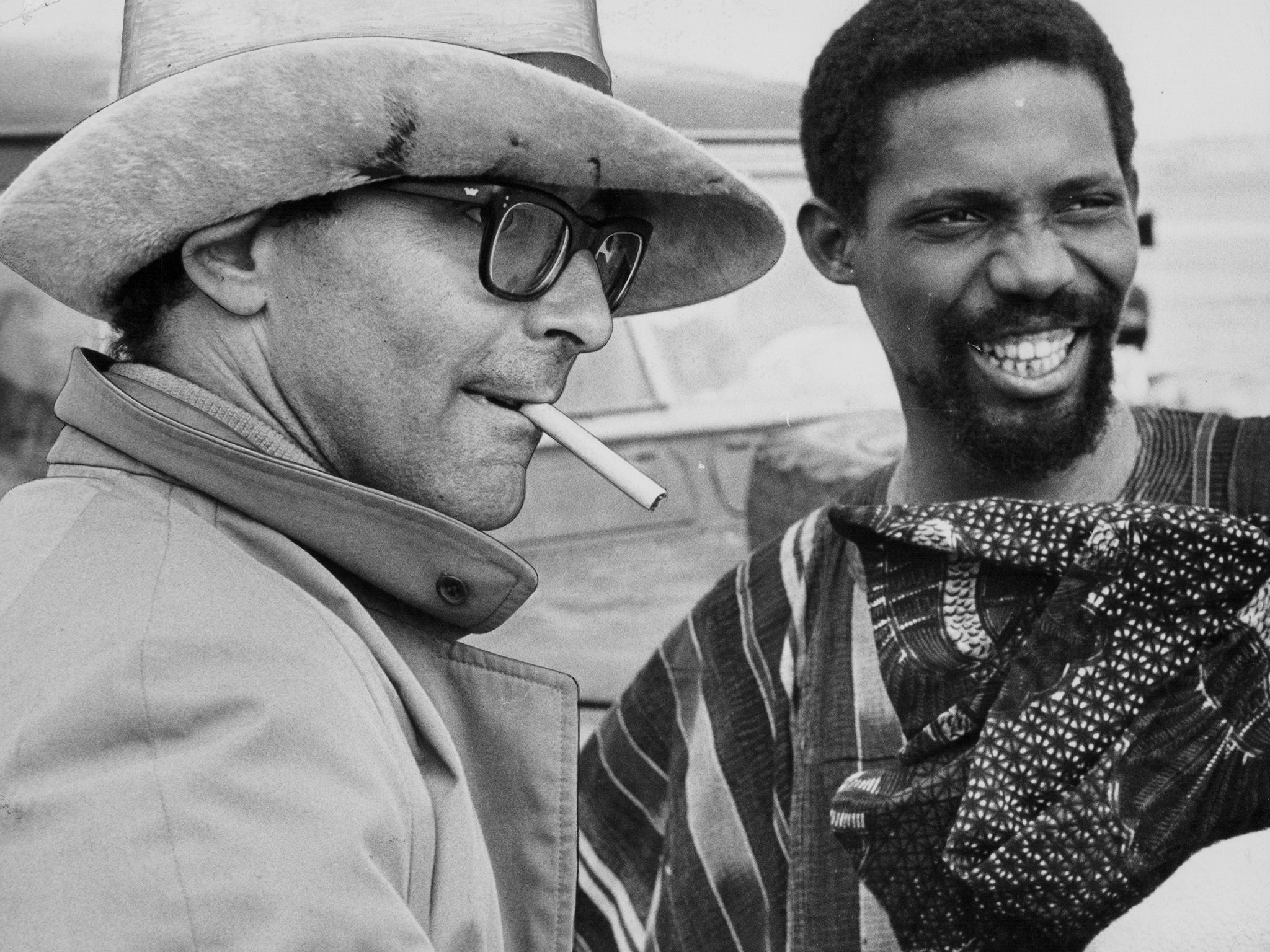

In person, Godard hardly looked like an imposing movie director. He had a slight build, with a high forehead, unkempt hair, dark glasses and an air of shyness. But he was by many accounts a prickly, unnerving and aloof man bristling with contradictions. Born to an affluent Franco-Swiss family, he became a committed Maoist. He also made commercials for Nike shoes when he needed money for other projects.

Stories proliferated of his difficult personal style. His first marriage, to the Danish actress Anna Karina, the star of several of his 1960s films, was riven with emotional abuse. He fell out with Truffaut in the early 1970s – over politics or women, or perhaps both – and the two never spoke again.

Jean-Luc Godard was born in Paris on 3 December 1930 and was the second of four children of a Swiss doctor and a French banker’s daughter. He grew up in Nyon, Switzerland, where his father opened a clinic.

He had settled in Paris by the late 1940s and embraced a bohemian lifestyle that included watching hundreds of films a year at a movie house that drew such like-minded cineastes and future directors as Chabrol, Rohmer and Truffaut. To support himself, Godard stole books from his grandfather’s collection of first editions and sold them.

While launching their careers behind the camera, the Young Turks of the New Wave were writing groundbreaking essays in the journal Cahiers du Cinema that championed filmmakers as artists in the tradition of novelists such as Dostoyevsky and painters such as Picasso.

Godard and his peers developed the “auteur” theory – insisting that a film should be regarded as the personal creation of the director, just as a poem was the personal creation of a poet and a painting of a painter. This was a novel perspective at a time when even marquee directors including Alfred Hitchcock were viewed as fine and distinctive big-studio technicians but rarely as artists.

After making short films, Godard vividly demonstrated the ideals of the New Wave with Breathless, about a gangster on the run (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and the American girlfriend who betrays him (Jean Seberg).

Breathless, one of Godard’s few commercial successes, brought out his contrarian nature. Soon after its release, he told an interviewer he hoped his next film would be a flop, explaining, “I prefer to work when there are people against whom I have to struggle.”

In the meantime, Godard continued to excite the film world with his next batch of movies, including A Woman Is a Woman (1961) and My Life to Live (1962), both of which starred Karina (as a stripper and a sex worker, respectively). She also was featured in Alphaville, a 1965 science-fiction fantasy presumably set in the distant future but filmed in contemporary Paris.

One of Godard’s most unlikely projects was Contempt (1963), for which he was given an unprecedentedly high budget by his standards – $1m. The picture starred Brigitte Bardot, the French actress renowned worldwide for her pneumatic figure and sexy pout. Godard fought with his producers, who wanted any excuse to show Bardot in the buff. He tacked on a nude bedroom sequence in which she asks her screenwriter husband (Michel Piccoli) to comment on every part of her body. The scene was more absurd than sexy.

Contempt was filled with allusions to modern filmmaking and offered a scorching portrait of the implosion of a marriage. It was also a commercial and critical disaster, although its reputation has improved considerably with time.

Weekend is often considered a turning point for Godard. He became engulfed in the student protests and strikes of 1968, proclaimed himself a Maoist, set up an independent production centre in Grenoble, France, and began turning out experimental videos full of communist ideology.

He grew so shaken by the thought of all remotely commercial cinema as essentially corrupting that he ended Weekend with two title cards: “End of Film”, followed by “End of Cinema”.

Godard’s marriages to Karina and actress Anne Wiazemsky ended in divorce. Since the early 1970s, he had been the companion and collaborator of the Swiss filmmaker Anne-Marie Miéville.

Re-emerging in the 1980s based in Rolle, Godard again embraced feature productions, and critics praised him as an impeccable visual stylist and masterful technician. He also lost none of his ability to provoke.

Inscrutability did not bother Godard. “I’d rather feed 100 per cent of 10 people. Hollywood would rather feed 1 per cent of 1 million people,” he once told the Los Angeles Times. “I’m always doing what is not done. And what I’ve never done is what everyone else is doing. I still think you can be an artist in making movies.”

Jean-Luc Godard, director and filmmaker, born 3 December 1930, died 13 September 2022

© The Washington Post