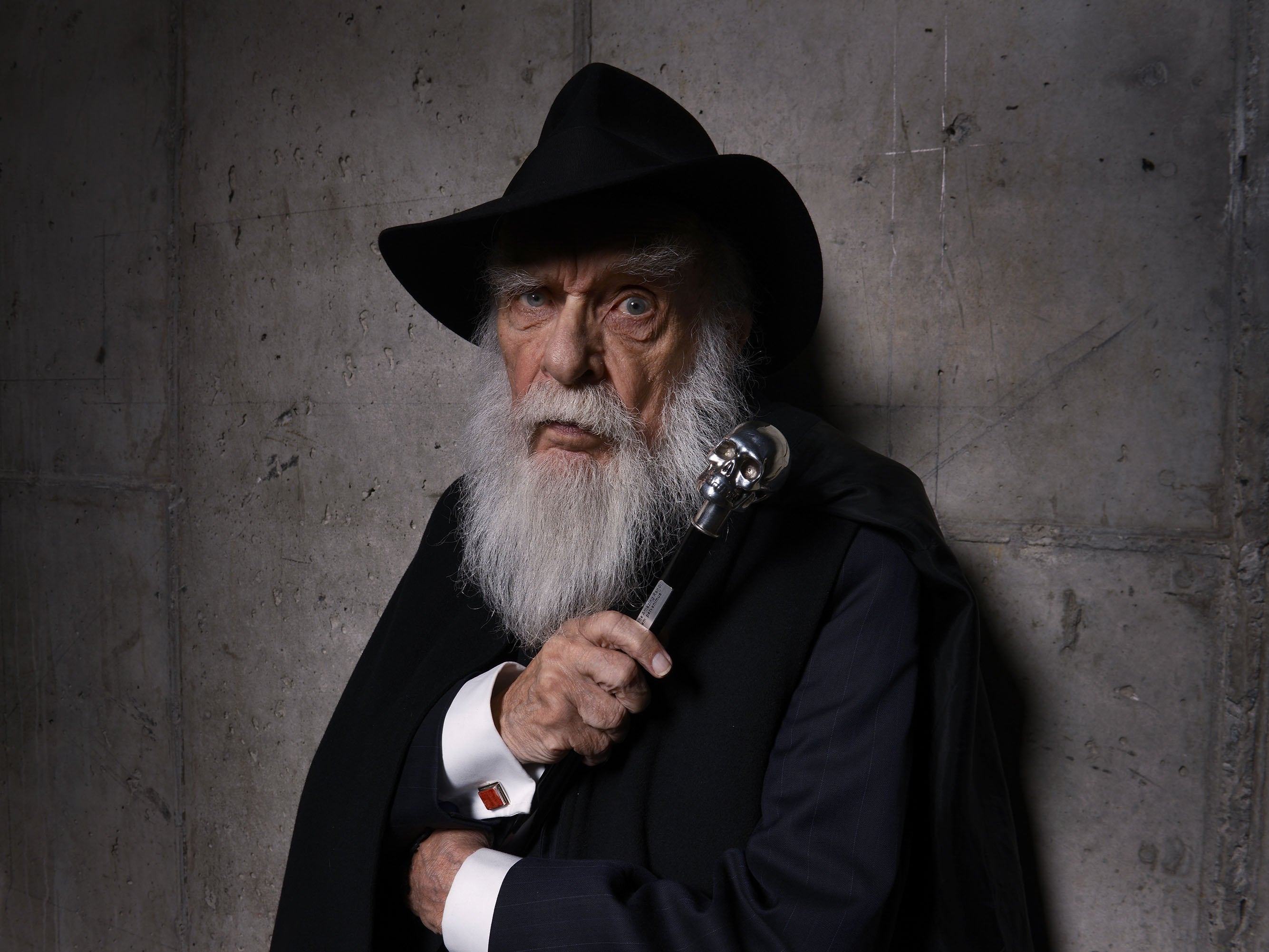

James Randi: Magician devoted to debunking the paranormal

Happy to describe himself as a ‘liar’ and a ‘cheat’, the performer insisted that magic is based solely on earthly sleight of hand and visual trickery

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.James Randi was an internationally acclaimed magician and escape artist, both praised and cursed for devoting much of his career to debunking all things paranormal: from spoon bending and water dowsing to spirit channelling and faith healing.

An inveterate sceptic and bristly contrarian in his profession, Randi insisted that magic is based solely on earthly sleight of hand and visual trickery. He scorned fellow magicians who allowed or encouraged audiences to believe their work was rooted in extrasensory or paranormal powers.

In contrast, the bearded, gnomish Randi cheerfully described himself as a “liar” and “cheat” in mock recognition of his magician’s skills at duping people into thinking they had seen something inexplicable – such as a person appearing to be cut in half with a saw – when it was, in fact, the result of simple physical deception. He was equally dismissive of psychics, seers and soothsayers.

“The difference between them and me,” Randi told The New York Times in 1981, “is that I admit that I’m a charlatan. They don’t. I don’t have time for things that go bump in the night.”

Still, he was always careful to describe himself as an investigator, not a debunker, and insisted he was always open to the possibility of supernatural phenomena but simply found no evidence of it after decades of research.

To put his money where his mouth was, Randi and the research organisation he helped found in 1976, the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, offered payouts ranging up to $1m to anyone who could demonstrate a supernatural or paranormal phenomenon under mutually agreed, scientifically-controlled conditions. While he had many takers, he said, none of them earned a cent.

“Randi is the man,” Michael Shermer, editor of Skeptic magazine, told the Times in 2001. “He's the pioneer of the sceptical movement.”

In stage appearances and on television, Randi – with his penetrating blue eyes and bushy eyebrows – duplicated mind-reading feats and other telepathic stunts with ordinary hand-and-eye trickery and exposed a number of popular faith healers as frauds.

At a public healing session led by televangelist Peter Popoff in Detroit in 1985, Randi sent in a man disguised as a woman, whom Popoff promptly “cured” of uterine cancer. Randi and his staff also discovered that Popoff wore a miniaturised radio receiver in his ear by which his wife relayed personal information – home addresses, type of illness – that she covertly collected from unwitting audience members so Popoff could impress them with his specific knowledge before proceeding to “heal” them.

For his efforts, Randi was condemned as an emissary of the devil, receiving hate mail and threats veiled in biblical references. He periodically wore a bulletproof vest. He was frequently sued for defamation and loss of income by those he pursued, but he claimed he never paid a dime in damages.

“They call me a ‘dried-up old runt of a magician’,” he told the Associated Press in 1986. “If I’m in their audience, they say a representative of Satan is with us today and point to me. I bow and wave.”

Most famously, he challenged Uri Geller, the charismatic psychic who stunned audiences with his mental spoon-bending act and other feats. Geller’s abilities underwent tests by scientists at the highly respected Stanford Research Institute, which reported that some information can be transferred “outside the range of known perceptual modalities” and warranted further study.

Conversely, Randi, after observing a spoon-bending performance by Geller at a private demonstration for Time magazine editors in 1973, dismissed it as phoney, saying he detected Geller inserting an already-bent spoon into the act.

Randi then duplicated the stunt with standard sleight of hand. The magazine wrote off Geller as “a questionable nightclub magician”, triggering a bitter, decades-long feud between the two men.

They exchanged angry potshots on national television and went to court in a series of libel actions filed by Geller. The litigation cost him thousands in legal fees, Randi said, but, as with the TV faith healers, he never paid any damages.

“In my view,” he told the Miami Herald in 1993, “Geller brings a disgrace to the craft I practise. Worse than that, he warps the thinking of a young generation of forming minds. And that is unforgivable.”

Randall James Hamilton Zwinge was born in Toronto on 7 August 1928. He was the eldest of three children of a telephone company executive.

A child prodigy with a reputed IQ of 168, he was shy and often lonely. Ravenously curious and bored by rote classroom learning, he sought refuge in the Toronto public library, becoming largely self-taught.

At a young age, he developed a keen interest in magic, inspired by a performance of legendary magician Harry Blackstone Sr. At 17, he dropped out of high school just days before graduation, turned down several college scholarships and joined a travelling carnival as a junior magician.

He overcame a stammer and fear of speaking in public, affected a turban and goatee, and honed his illusionist skills under a series of stage names, including Zo-Ran, Prince Ibis, Telepath and the Great Randall. He developed an early distaste for reputed psychic powers, challenging a preacher pretending to read the contents of sealed envelopes.

“I just want people to question, question, question,” Randi once said.

After a stint at simulating clairvoyance, in which many people took his prophecies seriously – he correctly predicted the winner of baseball’s World Series in 1949, for example – he said he was unable to persuade believers that his powers were strictly terrestrial. He said he “couldn’t live that kind of lie” and returned to conventional magic as The Amazing Randi, his permanent stage name thereafter.

He also became an escape artist in the manner of Harry Houdini, thrilling crowds by extricating himself from straitjackets, bank safes and jails. He escaped from a straitjacket while suspended upside down over Niagara Falls. He once held Guinness world records for surviving the longest time inside a block of ice (55 minutes) and for being sealed the longest in an underwater coffin (one hour and 44 minutes), breaking a record Houdini set shortly before his death in 1926.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Randi’s many appearances on television made him a fixture of prime-time entertainment. In 1973, he toured with heavy metal rock star Alice Cooper as an executioner simulating the beheading of the singer at each performance. By contrast, in 1975 he was invited to the White House by president Gerald Ford and first lady Betty Ford to do a special show for children.

By that time, Randi was already living permanently in the United States, first in Rumson, New Jersey, then Plantation, Florida. He changed his legal name to James Randi and, in 1987, became a US citizen.

Randi toured the world extensively, wowing throngs with his standard magic shows but also challenging claims of paranormal and other inexplicable phenomena, from household poltergeists and Ouija boards to flying saucers and reports of ships and planes lost in the Bermuda Triangle. All, he found, were based on exaggerated stories, media hype or physical manipulation.

Randi was the author or co-author of 10 books, many detailing his accounts of debunking paranormal and supernatural claims. Two focused on his disputes with Geller.

With the creation of his Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (later shortened to Committee for Skeptical Inquiry), Randi greatly expanded his research. To add heft to the committee, he recruited the public support of astronomer and cosmologist Carl Sagan and science fiction writer Isaac Asimov.

In 1986, Randi won a $272,000 “genius grant” from the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, much of which he spent on legal battles with Geller. A decade later, he founded the nonprofit James Randi Educational Foundation with a $2m donation from an anonymous computer mogul to further his agenda: maintaining a library, publishing a newsletter and setting up media-savvy blogs and websites.

In 2010, at age 81, Randi publicly announced he was gay. He had a long relationship with a Venezuelan-born artist, Deyvi Pena, who was arrested by federal agents in 2011 for passport fraud and for living under a false identity; he said he had been trying to avoid deportation to his home country, fearing homophobic persecution. Pena pleaded guilty in 2012 to passport fraud and served six months of house arrest. He and Randi were married in Washington in 2013.

Randi’s educational foundation announced his death, at the age of 92, but did not provide additional details. In recent years, he had been treated for cancer and heart ailments. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

In 2014, filmmakers Tyler Measom and Justin Weinstein released An Honest Liar, a full-length documentary of Randi’s life.

Raised loosely in the Anglican Church tradition in Canada, Randi described himself later in life alternately as agnostic and atheist. In one of his many essays, he questioned the religion of his early years as pointedly as others, jabbing at biblical accounts of creation, the virgin birth and the miracles of Jesus.

“The Wizard of Oz is more believable,” he wrote. “And more fun.”

James Randi, magician and stage artist, born 7 August 1928, died 20 October 2020

© The Washington Post