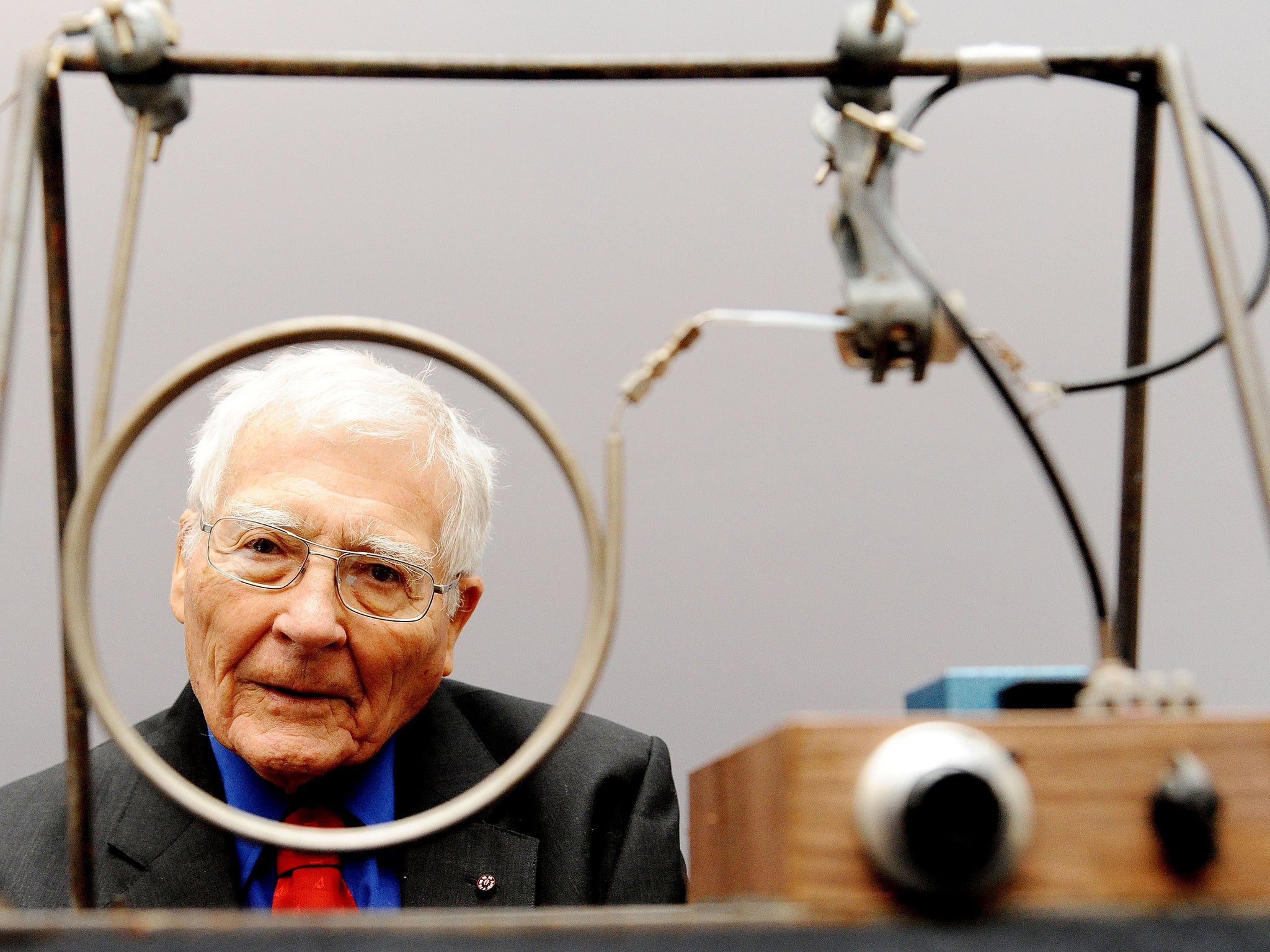

James Lovelock: Pioneer behind the ‘Gaia’ Earth hypothesis

The scientist’s theory challenged the orthodox view about life on Earth and also helped advance the study of climatology

James Lovelock was the pioneering scientist who first proposed and subsequently advanced the “Gaia” theory of Earth science, which has provided the much-needed context for understanding the current climate crisis.

Lovelock, who died aged 103, enhanced human comprehension of how Homo sapiens relate to the biosphere, the realm in which life exists on Earth. Published in 1979, his book Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth, put forward the theory that our planet and all life on it functions as a single “superorganism”.

Naming this superorganism after the Greek goddess Gaia, the personification of the Earth, he suggests that a complex symbiotic relationship between all living entities provides the basis for life itself. As a simple example, the presence of oxygen in the atmosphere, a result of respiration by early plants, brought about the conditions necessary for the development of animal life.

Although at first received with some scepticism, his theory has gained a significant following over the last four decades, especially amongst climatologists, and was built upon by Lynn Margulis, another key figure in symbiotic theory. He followed up his groundbreaking earlier publication with The Ages of Gaia (1988). This work in turn led to the 2001 Amsterdam Declaration on Earth System Science that: “The Earth behaves as a single self-regulating system comprised of physical, chemical, biological and human components.”

James Lovelock was born in Letchworth, Hertfordshire, in 1919 to Nellie and Tom Lovelock, who brought up their son as a Quaker. He graduated from Manchester University in 1941 with a degree in chemistry and received his PhD from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine seven years later.

From 1961, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, he was part of a team preparing the later Nasa Viking mission to Mars, where he was tasked with designing instruments that could detect the conditions for supporting life. His invention from this period, the electron capture detector, has since been deployed in other areas, such as monitoring chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the atmosphere and pesticide residues in water.

Comparing the conditions on Mars with those on Earth, Lovelock found that plant and animal life on this planet appeared to be part of an interlocking, self-regulating and self-sustaining system.

Thus, his early research into the possibility of finding life on other planets led to his later development of his Gaia theory about life on Earth. And based on his understanding of the Earth as a holistic self-sustaining system, Lovelock became an early and vocal campaigner on the dangers of global warming and its effect on disrupting Gaia’s delicate balance.

Writing for this newspaper in 2006, in an article he described “as the most difficult I have written”, Lovelock stated: “Our planet has kept itself healthy and fit for life, just like an animal does, for most of the more than 3 billion years of its existence.” He went on to warn that climate change would lead to a global catastrophe with the result that “billions of us will die and the few breeding pairs of people that survive will be in the Arctic, where the climate remains tolerable”.

His final book was Novacene: The Coming Age of Hyperintelligence (2019). Although non-fiction, it reads like science fiction, envisaging a future populated by benevolent robots which would protect Gaia. Unusually amongst climate campaigners, Lovelock favoured fracking and nuclear power as possible solutions to the environmental crisis, suggesting that atomic waste was far less a danger than carbon dioxide.

Lovelock was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1974 and received the Wollaston Medal from the Geological Society of London in 2006 for his work on the Gaia hypothesis. He was honoured by the Queen with a CBE in 1990 and made a Companion of Honour in 2003.

Stephen Harding of Schumacher College, where Lovelock taught in the Nineties, said in tribute: “There is no doubt that Lovelock was one of the most important scientists of all time. He was the first to realise that our planet is a gigantic self-regulating complex system that has maintained its surface conditions within the narrow limits favourable for life over vast spans of time because of a multitude of feedbacks between living organisms, rocks, atmosphere and waters.”

Lovelock was married to Helen Hyslop from 1942 until her death in 1989. They had four children. He subsequently married Sandy Orchard, who survives him.

James Lovelock, scientist, born 26 July 1919, died 26 July 2022

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks