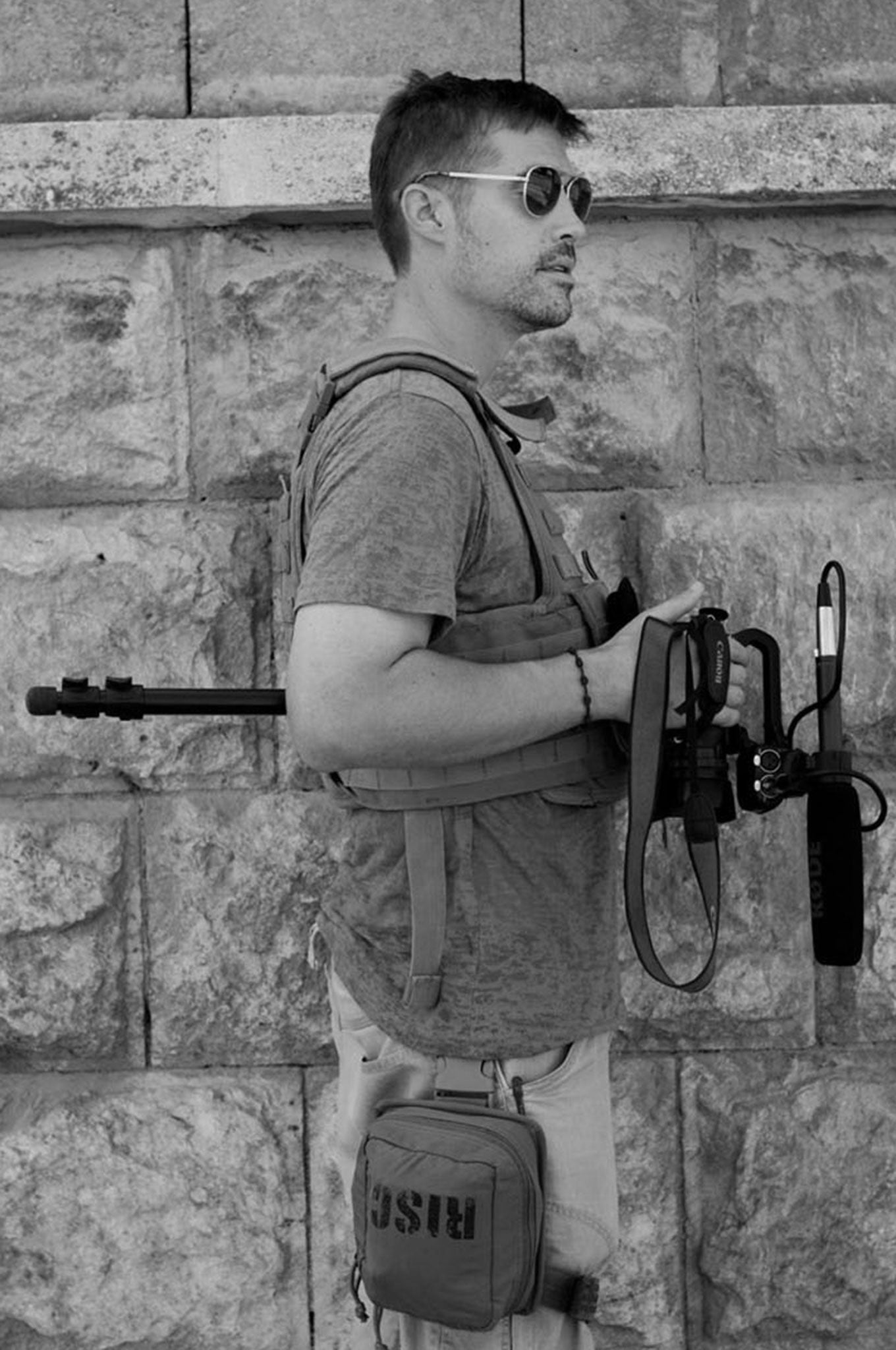

James Foley: Photojournalist respected for his pictures and admired for his courage who was murdered by terrorists

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.James Foley was one of the few to have explored the present Middle East turmoil from end to end – from Libya in the west to Afghanistan in the east. A man of easy charm and relaxed mien, he penetrated places where Westerners now fear to tread, and in his career in journalism demonstrated bravery unknown to many who have spent much longer in the business than his brief six years.

His photojournalism included searing pictures that went round the world of the difficulties faced by doctors in Syria trying to treat wounded patients under war conditions. Colleagues described him as a hugely talented photographer, capable of “breathtaking” shots with worn and battered video camera and kit.

Adversity did not faze him: colleagues, hearing with shock of his beheading, after two years in captivity, at the hands of the upstart Islamic State now controlling much of northern Iraq, all recall his ability, even in handcuffs in the bleakest of prisons, to keep up the general morale.

The tall, good-looking American, from Rochester, New Hampshire, would address all as “bro” or “dude” and anyone feeling cold or hungry in his company got his help. President Barack Obama paid tribute to him as a bringer of “hope and civility... That’s what Jim Foley stood for, a man who lived his work; who courageously told the stories of his fellow human beings.”

Foley appears to have been singled out from other Western captives in Iraq for especially brutal treatment such as beatings, and ultimately his chilling fate, because he was an American. His final nightmare began on 22 November 2012, when, having filed stories for GlobalPost and Agence France-Presse at an internet cafe in the town of Taftanaz in Syria, he and a translator took a taxi towards the Turkish frontier. The vehicle was stopped and he was seized by four gunmen; the translator was released.

Some might have called it foolhardy to choose the most anarchic places in the world for missions so soon after changing career, as Foley did, from teaching to investigative foreign reporting. But the history graduate, the eldest of five children, had a younger brother in the US Air Force, and curiosity burned within him about what was going on out there in the deserts over which American jet engines roared.

Foley wanted to see what was going on, from the ground. He took a freelance photojournalist job with GlobalPost, an online news service, and despite warnings not to go headed for Libya as the recently rehabilitated rogue state of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi dissolved into chaos in 2011. He embedded himself with the rebels closing in, and had his first blooding.

“A soldier’s pressing your face into the bed of a truck, bleeding from the scalp. It’s the worst kind of shock”, he said. The soldier was one of the forces still loyal to Gaddafi, which, on 5 April 2011, in the desperation of looming defeat, had ambushed and captured Foley and three other journalists at Brega, between Benghazi and Gaddafi’s home town of Sirte on Libya’s Mediterranean coast. It was Foley’s introduction to death: One of the four, his friend Anton Hammerl, from South Africa, was killed in the attack, and, Foley said: “I’ll regret that day for the rest of my life. I’ll regret what happened to Anton. I will constantly analyse that.”

The other two captured that day were Manu Brabo, a Spanish journalist, and a fellow American freelance, Clare Morgana Gillis. Foley, by advising her when to duck and when to run had, Gillis declared, saved her life twice before she had known him a month. She added: “We shared a cell for two and a half weeks, and every day he came up with lists for us to talk through. Top 10 movies. Favourite books. The fall of the Roman Empire and the rebirth of Western civilisation. Which famous person would you most like to meet? What’s your life story?” They were released after 44 days.

Telling the story of life in the modern Middle East as often as not had to yield to the need to help get colleagues out of trouble, and aid stricken families left behind. Foley made efforts while in Syria to help secure the release of the journalists John Cantlie and Jeroen Oerlemans, whom jihadists had kidnapped, and, for Hammerl’s children, he helped to arrange for a fund-raising auction of photograph prints to be held at Christie’s in New York.

Much of his inspiration was humanitarian, and he also raised money for an ambulance of the Dar-al-Shifa field hospital in Aleppo. He had a love for what he did,” one friend said, “and he wanted to tell the story of the Syrian people. Nothing was going to stop him.”

Foley told students on a visit home: “It was a kind of siren song that called me out to the front lines. It’s not enough to see it from a distance.” A colleague remembered Foley as wanting to linger in the most dangerous places, and as once having had to be got out from deep behind a hostile territorial boundary when he became stranded under shellfire with no transport.

Attractive to women, he appeared to have no girlfriend at the time of his abduction. He was unmarried.

A doctor’s son,he attended Kingswood Regional High School in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire; the family later moved the short distance to Rochester. He graduated in 1996 from Marquette University, a Jesuit college, where he studied history, and joined the Teach for America movement, giving lessons in schools in deprived areas in Arizona, Massachusetts and Chicago. He also taught prison inmates. One pupil remembered him as his basketball coach from middle school, leading the team to the district championship.

Foley took a course for poets and writers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, graduating in 2003, then joined Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, Illinois, graduating in 2008.

James Wright Foley, journalist: born New Hampshire 18 October 1973; died Iraq, death made known 19 August 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments