Jack Cardiff: Oscar-winning cinematographer celebrated for his work with Powell and Pressburger

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I met Jack Cardiff on a film set at Elstree Studios, he was busy heaving spotlights around and nipping up a ladder to adjust them. The legendary cinematographer was then 84. Cardiff's career spanned the best part of film's first century; he worked with many of the art form's greatest practitioners and was famed for his pioneering mastery of Technicolor. But, whereas others might have been content to rest on their laurels, pottering around the occasional festival or sitting on the odd panel as emblems of nostalgia, he remained active and passionate about movies throughout his life. His last project was the television documentary mini-series The Other Side of the Screen (2007).

The set on which I met him was for a low-budget student short film The Dance Of Shiva (1998), which was, at the time, still awaiting completion finance. None the less, Cardiff was thoroughly in his element and eager to share his decades of experience. "I've been carrying the torch long enough," he told me. "You younger people should take it; you can run faster than I can. Whatever you know, don't waste it, pass it on."

Cardiff was the quintessential showbusiness babe. His parents were music hall comedians and hoofers (his father had played professionally for Watford football club): Jack was, metaphorically speaking, born in a trunk. He made his screen acting debut at the age of four, in a film called My Son, My Son, and went on to appear in other silent movies including Billy's Rose, The Loves of Mary, Queen of Scots and Tiptoes.

In the twilight days of music hall, the Cardiff family looked to the new, upcoming medium of cinema for employment. Aged 15, Jack landed a job as a production runner (essentially, a message boy) on The Informer (1929), where his principal task was to keep the German director, Dr Arthur Robison, supplied with Vichy water. He graduated to clapper boy or camera assistant on films including Alfred Hitchcock's The Skin Game (1931). By 1936, he had risen to the rank of camera operator at Denham Studios in London when the Technicolor Corporation arrived there seeking trainees to start using the process in Britain.

Cardiff had little expertise of Technicolor. But, in the course of his itinerant childhood, he had had the chance to visit art galleries in many cities and developed a deep love of painting (he became an accomplished painter in his own right). Consequently he finessed the job interview by praising the use of light in the work of Rembrandt, Vermeer and the other Old Masters and became the camera operator on the first Technicolor film made in Britain, the 1937 romantic drama Wings of the Morning, starring Henry Fonda.

When the Second World War began, Cardiff made public information films for the Crown Film Unit, at times under dangerous conditions. One of his most notable projects was Western Approaches (1944), a docu-drama about a Merchant Navy vessel struck by a German U-Boat torpedo which was shot, remarkably given the conditions, in full Technicolor.

The turning point in his career came while working on the second unit of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943). They were impressed enough to hire him as their cinematographer on A Matter of Life and Death (1946). Cardiff's collaboration with this audacious directing-producing-writing team who revolutionised British cinema was a perfect marriage. As he was to recall, "I was always doing rather outrageous things. And that was Michael's entire way of working, so we got on famously."

Powell's first perverse idea for A Matter of Life and Death was to subvert audience expectations by shooting the sequences set on earth in colour and those set in heaven in black-and-white. But it was Cardiff who suggested shooting the heavenly scenes on Technicolor stock which, when processed as though it were black-and-white, gave them an eery, shimmering quality. For a celebrated early shot near the beginning, when the mist clears on a beach, Cardiff simply breathed on the camera lens, steaming it up for a couple of seconds.

Today, many of the guidelines of cinematography have been set in stone and – as Cardiff was often to bemoan – practitioners can rely on the lazy short cuts afforded by computer technology. He lived through a period when the thrilling possibilities of the technology were still being discovered. Many of his most memorable effects were achieved, not in post-production, but in-camera, through experiment, ingenuity and imagination.

Cardiff worked again with the team on Black Narcissus (1947), a torrid melodrama set in a convent in the high Himalayas but shot entirely at Pinewood studios in London. His ingenious use of painted glass backdrops and his fierily expressionistic deployment of colour won him an Oscar and a Golden Globe. His third and final film with Powell and Pressburger, the dance drama The Red Shoes (1948), experimented with optical effects, speeding up the camera to slow the action and make a ballerina seem to hover in mid-air; or doing the opposite in order to turn her into a blur of whirling pirouettes.

He was brilliant at transforming sets: his next projects, Scott of the Antarctic (1948) and Hitchcock's Under Capricorn (1949), were shot in the studio. But Cardiff had become a cameraman to travel and was just at home on location. John Huston's The African Queen (1951) took him up the jungle in Uganda and the then-Belgian Congo, where he fell ill from water poisoning (Huston and his star, Humphrey Bogart, were spared on account of the fact that they both drank only neat whisky). Bogie – as Cardiff related in his entertaining autobiography The Magic Hour, published by Faber and Faber in 1996 – sternly instructed him not to try to conceal the maze of wrinkles on his face.

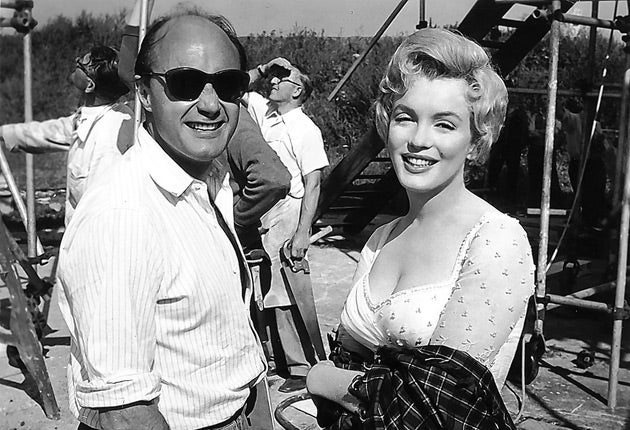

The cinematographer was, on the other hand, prized by actresses who knew they could rely on him to enhance their beauty. Among the many great stars he worked with were Ava Gardner (who warned him to light her differently while she was having her period), Sophia Loren, Gina Lollobrigida, Ingrid Bergman, Deborah Kerr, Marlene Dietrich, Gloria Swanson, Myrna Loy, Marilyn Monroe, Katherine Hepburn, Julie Christie, Bette Davis, Faye Dunaway and Audrey Hepburn.

In fact the list of his collaborators, both as a cinematographer and, eventually, as a director, reads like a compendium of cinema: it also includes Fred Astaire, Kirk Douglas, Christopher Walken, Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Joseph Mankiewicz, Laurence Olivier, King Vidor, René Clair and Jacques Feyder.

Cardiff turned to directing in 1953, but his first attempt, William Tell, starring Errol Flynn, was thwarted when the funding collapsed; only a few minutes of footage remain. Sons and Lovers (1960) fared better: an adaptation of the D.H. Lawrence novel starring Trevor Howard, Dean Stockwell and Wendy Hiller, it got six Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director. Freddie Francis won an Oscar for his (black and white) cinematography.

In the same year, Cardiff made Scent of Mystery, a curiosity shot in Smell-O-Vision, a process which pumped odours into the cinema at appropriate moments in the story. Another of his intriguing films as director was The Girl on a Motorcycle (1968), an erotic drama starring Alain Delon and a leather-clad Marianne Faithfull as a married woman who zooms off on a motorbike odyssey to meet her lover.

Cardiff then abandoned directing, but remained a prolific cinematographer whose credits included Death on the Nile (1978), Michael Winner's remake of The Wicked Lady (1983), Conan the Destroyer (1984), Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) and Million Dollar Mystery (1987). This period was hardly the cinema's finest hour, but he would later talk of these films with as much enthusiasm as he did when speaking of the authentic masterpieces he had worked on. After earning two further Academy Award nominations for his cinematography on War and Peace (1956) and Fanny (1961), he was made an OBE in 2000 and received an honorary Oscar in 2001, the first technician to be thus honoured and only the second Briton selected after Laurence Olivier.

In a sly post-modern moment in A Matter of Life and Death, a messenger who descends to earth from the monochrome celestial world, sniffs appreciatively at a bright red flower and muses, "One is starved for Technicolor up there." That shortage has been rectified this week. The earthly world, on the other hand, became a shade or two greyer.

Sheila Johnston

I came to know a very warm and quite unique individual with a wicked sense of humour, a man who had time for many, whatever their beginnings (providing they did not bore him), writes Betty Lowe. I first met Jack Cardiff as the daughter of a dear friend of his wife Angela, who was known as Niki. He became a close friend of the family, and then years later, as a journalist, I interviewed him a number of times, once for the Independent's magazine, which published his exceptional portraits of Marilyn Monroe.

At the time he was introduced to my family, Jack was working on a script of James Joyce's Ulysses; he eventually fell in love with and married his script editor, Niki. They had a son, Mason, christened after James Mason, his godfather, who at the time was a friend and neighbour in Switzerland.

Jack had almost royal status in our family and I remember as a child being screamed at to tidy up because he was coming to visit our cluttered, chaotic house in Chiswick. At the beginning he was slightly perturbed by this unruly West Indian/Jewish family he had inherited from his wife, but eventually he started to blend in.

My mother showed him off whenever she could; Jack was always gracious, humble and kind. When he visited, he would settle down and talk for hours to my father, Uli, about Greek mythology, or how long it might take him to learn Hebrew. His thirst for knowledge was unending. Everything was source material.

At the time of taking the portraits of Monroe, he was filming The Prince and the Showgirl. He told me he had arranged a 10am meeting at his apartment. "Marilyn turned up eight hours later with Arthur [Miller], having slept all day, but she looked gorgeous and luminescent, almost, after so many hours of sleep, as fresh as a baby – and I took wonderful shots of her that day".

I stayed and worked with the Cardiffs when they lived in Switzerland in the Seventies. Jack returned because he loved England, and missed his cricket and football – he was an ardent Arsenal fan. He had also been a member of a celebrity branch of the MCC and often played charity matches with James Mason and Peter Sellers and other film-industry cricketers.

There is a legendary story that while still based in Switzerland he was called to play a game in Scotland, and drove all the way. He got out of his car and was bowled first ball, upon which he climbed back in and drove straight back to Switzerland.

Some years ago I went to Hollywood with the Cardiffs to cover Jack being awarded a Lifetime Achievement Oscar. He and Niki were installed in the Beverly Hills Hotel and every day a stream of film students, directors, producers and screenwriters came to talk about future projects; Jack soaked up the attention as if he was back home in Hollywood's golden era.

Many feel that it was only after he won his Lifetime Achievement Oscar that BAFTA recognised him, honouring him with a Lifetime Achievement award in 2001. After the ceremony, his wife recalled, "a man from the Academy came up to me and apologised, saying how ashamed he was that England hadn't honoured him earlier."

Cardiff had Mason at 56. He did not want to miss a fraction of his youngest child's years. "He wanted me with him all the time," Mason recalled. "He said, 'Just travel with me and you will learn everything you need to direct'."

He died peacefully at 1.30am, surrounded by his sons, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The hearse collecting his body pulled out of the house and the family watched it trickle slowly down the road and over the horizon. It was about 4.30am, "The Magic Hour", the times at sunrise and sunset when the light, as Jack said in his autobiography, most inspired him in his craft. As Niki said, "He gave us the perfect Hollywood ending".

Jack Cardiff, film director and cameraman: born Great Yarmouth, Norfolk 18 September 1914; Academy Award for photography, 'Black Narcissus', 1947; OBE, 2000; Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement, 2001; BAFTA Special Award, 2001; married three times (four sons, one stepson, one stepdaughter); died Ely, Cambridgeshire 22 April 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments