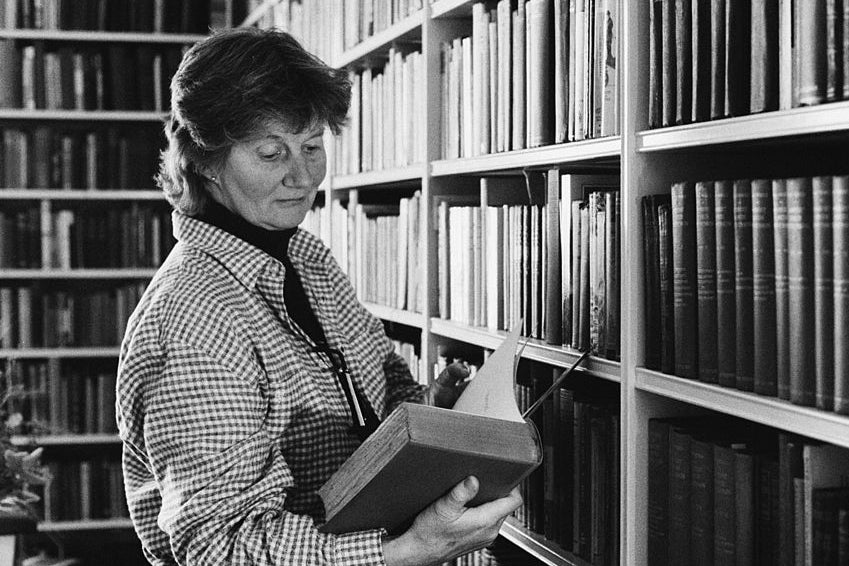

Iona Opie: Amateur scholar behind 'The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes' catalogued centuries of childhood

A labour of love started with her husband Peter in the 1940s and led to the couple becoming Britain's foremost experts on children's ditties, games and folklore

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The world’s leading authority on child lore and nursery rhymes, Iona Opie combined a grace of spirit with a capacity for the daily toil of fact-grubbing research that knew few equals. Working for nearly 40 years with her husband Peter, she wrote a number of ground-breaking reference volumes, publishing her own books for another two decades after his death in 1982.

She presided for years over an empire of books, toys, games and cuttings stored in the couple’s rambling country house in West Liss, Hampshire.

Brought up in South-east England, Iona only saw her pathologist father Sir Robert Archibald once a year when he returned from a posting in Sudan.

A serious child much given to reading, she enjoyed a comfortable although disciplined childhood before enrolling in 1941 at Middle Wallop, Salisbury Plain, in the Woman’s Auxiliary Air Force. She chose to train there as a meteorologist.

She came across I Want to be a Success (1939), a book by Peter Opie, illustrated by his own photographs. Her letter to the author via his publishers elicited a 45-page response.

A hastily arranged meeting in London led to an intense, burgeoning relationship, with Peter pursuing marriage but Iona less keen, wanting instead to go to university after the war to read botany. Peter finally got his way in 1943. Pregnancy followed soon after, with Iona leaving the Air Force a year later and having her first baby before the age of 21.

One day, out for a walk, the young couple saw off a visiting ladybird with the traditional chant: “Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home.” Wondering where the rhyme came from and who wrote it, their next library visit led to some fascinating but inconclusive research on the topic, and the path ahead suddenly seemed clear. Husband and wife immediately started work on the first of their many enterprises: a collection of traditional rhymes, taunts, tricks and teases appearing under the title I Saw Esau in 1947.

Letters poured in, including contributions from Robert Graves and George Bernard Shaw. Moving to the country in 1946, the couple scraped by and eventually produced the most famous book of their long partnership: The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (1951).

Now with three children, they drew on their own growing collection of antique books and illustrations, as well as the Bodleian Library, to produce a scholarly work so charming and erudite it became popular. Researching into more than 500 rhymes, songs, nonsense jingles and lullabies, this book magisterially punctured many long-held myths, such as the supposed association of the Great Plague with Ring-a-Ring-a-Roses or the identifying of Humpty-Dumpty with Richard III. It led to a post-war renewal of interest in nursery rhymes, with a rush of new, illustrated anthologies.

In 1955 their Oxford Nursery Rhyme Book came out, featuring more than 800 nursery rhymes.

Discovering lore going back as far as history itself, the Opies took a far more optimistic view about the essential continuity of the culture of childhood. The next book, Children’s Games in Street and Playground (1969), proved to be Iona’s own favourite and was the product of 10 years of research.

As the distinguished anthropologist Edmund Leach pointed out at the time, this book marked a transition from folklore studies to something much closer to anthropology – a remarkable feat for these amateur scholars, neither of whom ever went to university or taught at one. The authors’ interest in the games children play now came second to their fascination with a child’s natural capacity for organisation, rule-making, learning and teaching. To assemble this material, in addition to her usual meticulous historical research, Iona spent much time in her local primary school.

Notebook in hand, she would record each game as it came and went during hectic playground sessions. Drawing on contributions from what was now a small army of faithful correspondents, as well more than 10,000 children all over the British Isles, Peter and Iona painstakingly divided contents between Starting Games through to Acting and Pretending Games.

A photograph, taken in 1962, shows the couple at their local school joining in a skipping game under the critical gaze of a group of junior pupils. But for much of the time, this sort of fun was rare. Money was always a problem. With no grants or university funding, the Opies never earned more, as Iona once put it, than a police constable might bring home in any one year. Only being able to afford a car in 1959, and with any spare money usually going on their growing book collection, the couple habitually bought second-hand clothes, never went on holidays, and when greens were expensive they sometimes ate nettles gathered locally. At home, husband and wife operated in separate rooms, with Iona the archivist and Peter taking charge of the writing. Every day followed a strict regime, with each person at their desk by 9am and then exchanging notes on the next section as it was being written and then inevitably rewritten, often late into the night.

Peter’s perfectionism, although often difficult to live with, served the couple well. Seldom can scholarly books have been written with such lightness of touch and economy of words. But nervous and sometimes irascible, complaining about his children’s noise and fighting for every word to be just right, he proved a hard taskmaster. Yet although different in temperament, husband and wife always shared a deep love of the past, feeling that they knew figures now long dead far better than they were acquainted with any of their actual contemporaries.

By the time of Peter’s death from heart failure, their grown-up sons James and Robert were distinguished collectors in their own right, and daughter Letitia a trained social worker. Iona continued with her studies in child folklore.

Following the enthusiastic, countrywide response to an appeal headed by Prince Charles in 1986, Oxford’s Bodleian Library was finally able to acquire the entire Opie Collection of Children’s Literature – the largest collection of children’s books still in private hands.

Valued at £1m, this was offered by Iona to Oxford at half that price, so eager was she to keep the 20,000 items together in one good home. The two-year fundraising campaign won widespread national recognition for the dedication shown by the Opies over the years to collecting rare books, comics and children’s magazines often unrecorded in the British Library and therefore at risk of ultimately disappearing altogether.

In 1999, Iona was awarded the CBE for her services to scholarship.

By now Iona was beginning to tire of the hard grind of filing, compiling and writing. Interviewed in 2005, she admitted that she had become “very bored” with child lore, wanting to move on and quoting “opsimathy” – education late in life – as her main hobby in her entry for Who’s Who. Yet despite occasional loneliness, growing deafness and an increasing unwillingness to appear in the media, her enthusiasm for children and their favourite rhymes and games never really slackened. She would still open a nursery rhyme book every morning before starting the day, reading from it at random. Speaking in the same year, she declared that: “If you acquire a nursery rhyme-ical attitude, you’re not at all put out by life’s little bumps and bruises. They just seem funny and entirely normal.”

Iona Margaret Balfour Opie, writer and folklorist, born Colchester 13 October 1923, died 23 October 2017

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments