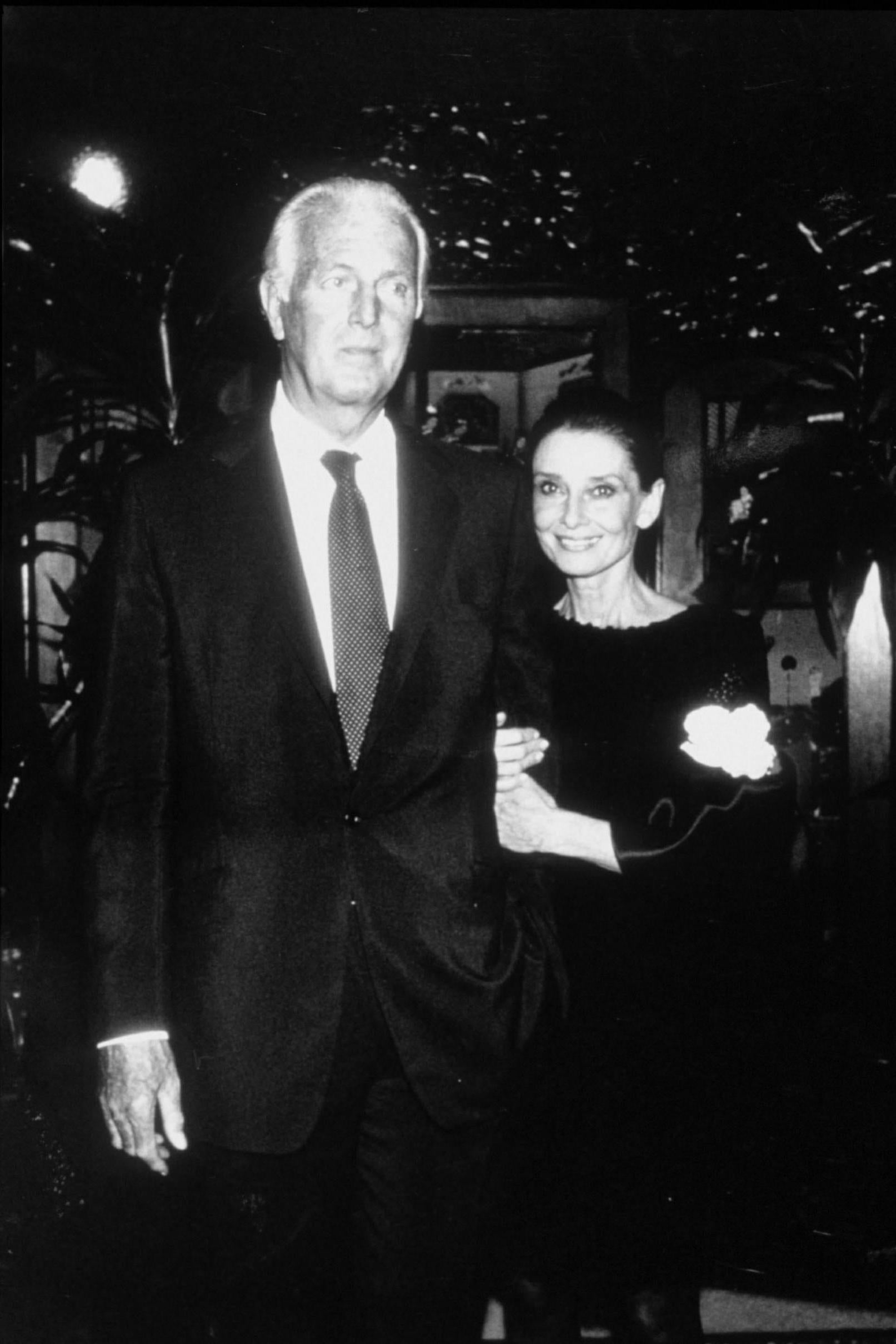

Hubert de Givenchy: French fashion designer whose brand of elegance informed the Fifties and Sixties

By the time he retired in the mid-Nineties, his designs had expressed more than four decades of style, inspiring – and inspired by – women such as Audrey Hepburn and Jackie Kennedy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fashion is a topiary art. Hubert de Givenchy, who died aged 91, understood more than most the importance of cut and mastered it to create clothes of arresting simplicity for the haute couture and ready-to-wear markets. “I love purity and refinement,” he once said – his very signatures.

Jackie Kennedy and Audrey Hepburn became the female embodiments of his style, dressed in small-collared suits with narrow, inset sleeves, slim dresses with petite shoulders and architecturally precise evening coats with dramatic dolman sleeves.

Givenchy’s candid, strict lines were lightened by a raffine, offbeat nonchalance which Chanel had proved to be the height of worldly sophistication. This understated elegance once even influenced the dress of the Queen.

Givenchy saw women in their entirety, leaving nothing to chance. He designed their shoes, bags, gloves, hats and trinkets. Like Cristóbal Balenciaga, his great friend and mentor, the cut clothes close to the body without ever seeming to touch it, giving a woman an insectile silhouette, in which the shedding of a coat would seem like the discarding of her shell.

Givenchy’s millinery was pure fantasy: an overblown peony balancing on a pillbox, a space helmet knotted with a stiff grosgrain bow under the chin, or an eye-shading fringe of marabou feathers tangling with her false eyelashes. Worn by women with a what-the-hell insouciance, they were considered madly beguiling, though some gumboot-minded English men found them oh-so-slightly ridiculous.

For generations, Givenchy’s family had lived in Beauvais, in France, where his maternal grandfather was a pupil of the painter Corot and later the general manager of the Gobelins and Beauvais tapestry manufactory.

Reared in a fatherless environment – Lucien Taffin de Givenchy died of influenza in 1930 – he was inevitably immersed in a feminine world in which his beautiful mother was addicted to exquisite clothes and materials. These became a source of inspiration to him.

Like many aspiring couturiers, the young Givenchy designed clothes for his dolls and would accompany his mother to the Parisian couture houses and textile merchants to select her wardrobe.

“I would beg her to let me see and feel those wonderful materials,” he recalled.

This haute bourgeois upbringing in a matriarchal household nurtured the young man’s impeccable manners and the easy charm with which the archetypal French gentleman handles women. He was at ease with the opposite sex and enjoyed an innate understanding of their fripperies: it won him their admiration and loyalty as a couturier.

Leaving school at 16, Givenchy was urged by his mother to take up law. Though he studied in Paris to become a solicitor’s clerk he longed to enter couture.

The opportunity arose during the war when he met Jacques Fath, a leading couturier, who became his first employer. Moving on to work with Roger Piquet and Lucien Lelong (alongside the young Christian Dior) and Elsa Schiaparelli, he served his apprenticeship, crediting Schiaparelli as the finest teacher of true French chic.

His debut collection under his own name, in 1952, was a daring gamble at a time when Dior’s ultimate luxury dominated high fashion. He sent his models down the catwalk in simple, mix-and-match cotton shirting separates – the understatement was as refreshing as a long glass of iced water after too many rich truffles.

Fortunately the press thought it was a darling idea. In fact Givenchy had turned to shirting because he could not afford to invest in luxury fabrics. He was given the prestigious cover of French Elle and customers flocked to buy his readymade or just-one-fitting casual wear.

Internationally, Givenchy was regarded as the last aristocrat of couture, favoured for his regal simplicity.

Six-foot-six tall and presenting an elegantly relaxed demeanour, Givenchy adopted Balenciaga’s idiosyncrasy of always wearing a white smock in the studio. This gave him the air of a dashing medical practitioner, a Gallic Dr Kildare. To be dressed by Givenchy seemed to promise a cure for every woman’s ills.

Givenchy soon established a prestigious couture house and, following the retirement of Balenciaga in 1968, inherited many of his craftsmen, and clients, for on closing Balenciaga introduced them to his protégé.

Applauding impeccably simple, sporty day clothes and ravishingly luxurious evening dresses, Givenchy combined an innate sense of tranquil subtlety and grand-occasion dressing. By developing a rapport with the leading cloth merchants he persuaded them to provide exclusive runs for him based on his own designs, such as fruit and vegetables embroidered onto organdie, linen or satin, and appliques based on wood carvings or Delft china.

The height of his creativity was the late Fifties and early Sixties when he amalgamated the insouciance of the “Beat” look – knitted sleeved jerkins, short tweed skirts and head scarves – with the quiet tailored clothes of a gamine duchess. His costumes for Audrey Hepburn’s in films such as Breakfast At Tiffany’s (1961) and Funny Face (1957) alluringly defined the image of a modern, high-born, tiny-boned waif, whose understated dress suggested confident refinement.

Givenchy juxtaposed an artistic sensibility with keen commercial acumen. He developed 180 licence operations throughout the world, including scent, hosiery, furs, sportswear and home furnishings. These “annex activities” were administered by his staff to ensure that the house style was not abused. He even signed his name to the interior design of a luxury Lincoln Continental.

Givenchy appreciated the lucrative importance of the American market and travelled there at least twice a year to serve couture clients and win money-printing contracts with American manufacturers for whom he designed logo-ed collections.

In 1986, seeking to find someone to run his empire while concentrating on design, Givenchy sold his business to LVMH (Louis-Vuitton-Moet-Hennessy). Givenchy found himself in a curious position by the end of the Eighties: he was in the same stable as his main couture rivals Dior and Lacroix.

Givenchy was steadfast in his loyalty to the art of couture. “The most infuriating thing,” he once said,” is to be asked if the couture is dying.

People don’t keep rushing off to the baker and asking him if he is going to go on baking bread tomorrow. Of course he is, as long as people want it. And it is the same with haute couture. Haute couture is prestige and we need prestige.”

He was always fired by the pursuit of beauty, whether it be in the creation of a beautiful evening gown, a good raincoat or a magnificent home. Decorating and redecorating houses, boats or cars were his passion. In Paris he resided in a magnificent hotel particulier on the rue de Grenelle, where the deep green walls provided a perfect backdrop for his important collection of late 17th- to early 19th-century furniture and bronzes. From the early Sixties, once his couture reputation began reaping financial rewards, he pioneered the rediscovery of Boulle-style furniture of the Louis XIV epoch. His first important purchase was a Boulle marquetry armoire which had belonged to Misia Sert.

In 1976 he bought his dream country house, the 17th century Manoir du Jonchet set in open farmland near Versailles on the outskirts of Paris. He lovingly accumulated an impeccably selected assortment of fine furniture, 20th-century paintings, including Picasso and Miro, and exotic chinoiserie. He also kept a home at Cap Ferrat on the Cote d’Azur. Many of the finest pieces were sold at Christie’s in the autumn of 1993. This released funds which allowed him to continue collecting other objects.

Givenchy extended his visual passion to gardens and horticulture; each abode stood in a handsome and historically appropriate garden; each friend was remembered with their favourite flowers on birthdays, anniversaries or days when he simply wanted to remind them of his friendship. He restored the Potager du Roy at Versailles, a task he undertook as President of the World Monuments Fund of France, a position to which he was elected in 1992.

His landscaped gardens were admired by connoisseurs; gardens with curlicues of boxwood, a pool overlooked by a pavilion d’amour and an ornamental lake. “I am a Pisces, I love water,” he said. He was a bachelor and his homes and gardens housed whippets and daschunds to “fill the house with life”.

Though surrounded by the rigid formality of the typical Parisian vendeuses, Givenchy himself was a very approachable and relaxed man. I recall visiting him on several occasions at his couture house on the Avenue George V.

Once, having struggled through the barrage of protective assistants – those stickleback spinsters in neat grey flannels and pince-nez – and climbed up the imposing ruby-carpeted staircase to the piano nobile, I arrived in the relaxed surroundings of Givenchy’s private studio. With a gentleman’s modesty, he preferred to applaud the talents and influence of his beloved Balenciaga than to trumpet his own successes. He was always keen to impress upon one the importance of beauty as an uplifting and civilising influence.

He had a reassuring, gentle and father-like manner which was so enjoyed by his staff, his friends and his family. Over 30 years he developed a close and platonic friendship with Audrey Hepburn, dressing her in public and private, helping her with her charities and offering tender care when she was dying of cancer. He sent a private plane to fly her back from America so that she could spend her final days at her home in Switzerland, surrounded by little posies of sweet-smelling lily of the valley – her favourite flowers that he always sent to her.

By the end of 1995, Givenchy had presented his final collection. He had given women more than four decades of elegance. Once vulgarity overshadowed refinement sometime in the Sixties, Givenchy no longer won the headlines but his sound, delicate good taste served women of refinement until he retired.

Succeeded by John Galliano and then Steve McQueen, his label was handed to Riccardo Ticci in 2005 whose muses included Kim Kardashian and Kanye West.

In 2007 he said: “I suffer. What is happening doesn’t make me happy. After all, one is proud of one’s name.”

When the first woman to run that name was appointed last year – Clare Waight Keller – the first thing she did was to court an audience with Givenchy.

We have lost the last gentleman of haute couture and one of its most staunch defenders: “If we lose the couture we will lose a great deal of beauty, something very special would vanish. I believe that there will always be a place for this beauty and there will always be women who want beautiful clothes and who dream beautiful clothes. And my clothes fulfil that dream.”

In 2010, he told the Oxford Union: “You must, if it’s possible, be born with a kind of elegance. It’s part of you, of yourself.”

He is survived by his partner and fellow designer Philippe Venet.

Count Hubert James Marcel Taffin de Givenchy, French fashion designer, born 21 February 1927, died 10 March 2018

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments