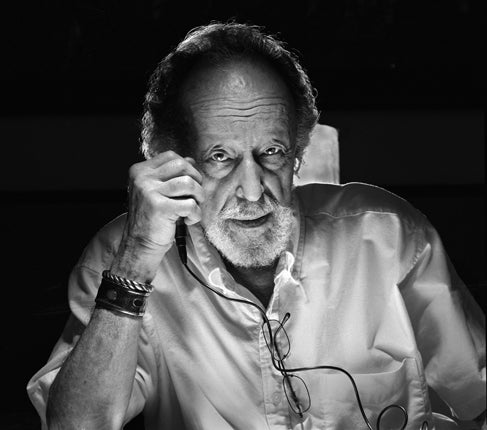

Herman Leonard: Celebrated photographer whose work helped make jazz the epitome of cool

Photography has proved a crucial medium in spreading the popularity of jazz and making the music and its creators the epitome of cool.

The American photographer Herman Leonard helped turn performers like Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker and Frank Sinatra into the iconic figures they remain. The backlit, black-and-white pictures he took in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s seemed to capture the smoky, shadowy atmosphere of the New York clubs where the singers and musicians appeared, and almost to resonate with their music. Leonard became the most celebrated of jazz photographers, with several coffee table books, exhibitions and documentaries to his name. His photographs adorn postcards and calendars as well as restaurant, office and living room walls the world over, but are also valuable documents of a bygone age and held in collections such as the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

He was born in 1923, the youngest child of Romanian immigrants who had settled in Allentown, Pennsylvania. His brother Ira dabbled in photography and he became fascinated by the developing process. Leonard's interest in the minutiae of photography helped forge a trademark style which involved a degree of experimentation at every stage, great attention to detail and a mastery of printing techniques. In 1935 his brother gave him a camera and he began taking pictures at school, including the portraits that appeared in the yearbook. He subsequently enrolled at Ohio University in Athens, the only university to offer a course in photography at the time, and graduated in 1947 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree.

His studies were interrupted by his army call-up, and he spent two years as an anaesthetist with the 13th Mountain Medical Battalion in Burma. Even while under fire he managed to take and develop the occasional photograph, though his Second World War pictures were only published in Jazz, Giants & Journeys: The Photography of Herman Leonard in 2006.

For a few months in 1947 he worked as an unpaid assistant to Yousuf Karsh in Ottawa, Canada. He picked up lighting tips from the leading portrait photographer of the day and also observed the way he put his subjects at ease. Karsh encouraged Leonard to go it alone and in 1948 he set up his own studio in Greenwich Village in New York, an ideal location to combine commercial work in the daytime and photographing the jazz greats and documenting the emergence of bebop at Birdland, the Blue Note and Village Vanguard in the evening.

A keen jazz fan, he was in his element. "I took advantage of being a photographer to get myself into the clubs so I could sit in front of Charlie Parker," he said. "I got to listen to the music in person. It happened in the clubs, not in a photo studio. I wanted to create a visual diary of what I heard, to make people see the way the music sounded."

Using only a couple of lights with his 4x5 Speed Graphic camera, he managed to achieve in situ what Karsh had done in the studio and created enduring, evocative, film noir-like images of artists such as Lena Horne, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Nat "King" Cole and Thelonious Monk. He sold these to record companies such as Verve and magazines like Down Beat, and gave prints to the musicians and club owners who had been so helpful.

He famously shot Holiday at home, cooking steak for her dog, and formed lifelong friendships with Tony Bennett, Dizzy Gillespie and Quincy Jones, who said: "I used to tell cats that Herman Leonard did with his camera what we did with our instruments. Looking back across his career, I'm even more certain of the comparison: Herman's camera tells the truth, and makes it swing. Musicians loved to see him around. No surprise; he made us look good."

In 1956, Leonard accompanied Marlon Brando as his personal photographer on an extensive trip to the Far East. He then moved to Paris and established a great rapport with Eddie Barclay, a pianist, jazz fan and entrepreneur who had just launched his own record label and would soon employ Jones and Davis, too. Over the next two decades, Leonard photographed many of Barclay's leading acts, including Charles Aznavour, Jacques Brel, Dalida, Sacha Distel and Henri Salvador as well as the US jazz exile Chet Baker, and took the celebrated shots of British rock'n'roller Vince Taylor in black leather. While in France, he branched out into advertising, fashion and travel photography and also served as European correspondent for Playboy magazine. In 1961, he photographed Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington while they were making Paris Blues, the film starring Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier, and directed by Martin Ritt.

Like many free spirits, Leonard eventually moved to Ibiza, in 1980. He was "flat broke" and began taking stock of his life and sifting through the thousands of negatives he had amassed over the years. In 1985, Filipacchi published his first book, L'Oeil Du Jazz [The Eye Of Jazz]. Its cover, a still life composition of a Coca-Cola bottle, a music score and Lester Young's hat, cleverly conveys the very essence of the saxophonist. "I like to photograph images – particularly of well-known people – where you don't see their face, but the image does express part of their personality," Leonard said.

Three years later his first retrospective, at the Special Photographers' Gallery in west London, attracted more than 10,000 visitors. Consequently he was rediscovered in the US and eventually returned there and published a second book, Jazz Memories, in 1995. He settled in New Orleans, a fateful decision given the havoc wrought by Hurricane Katrina in August 2005. Thankfully, many of his negatives had been sent to a vault at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, but his home and studio were badly damaged and he relocated to Los Angeles. The British film-maker Leslie Woodhead made the memorable BBC documentary Saving Jazz about Leonard's post-Katrina experiences, which mirrored what happened to New Orleans' vibrant jazz community. Leonard and Woodhead also collaborated on a book, Jazz, due for publication in November.

Last year Leonard was official photographer for the Montreal Jazz Festival. More recently, he had spent time with Lenny Kravitz in the Bahamas, documenting the genesis of the rock musician's soon-to-be released album.

Asked about how visionary his work was, Leonard was typically self-deprecating. "When I was photographing Miles or Dizzy in the early days, I knew these were good and important musicians, but not as important as they turned out to be. I had no idea," he said. "If I had any inkling, I would have shot 10 times as many pictures. Ninety-nine percent of everything I shot was off the cuff. I wanted to capture what was really there untainted by anything I would do. My whole principle was to capture the mood and atmosphere of the moment."

Davis, whom he photographed again at Montreux in 1991, shortly before his death, was undoubtedly his favourite subject. "The skin quality was like black satin," Leonard said last year. "The bones were well defined and those burning eyes of his were so intense that for a photographer it made it very easy. He was just beautiful."

Talking about his famous image of the tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon in the smoky haze of the Royal Roost Club in New York, he said: "That smoke was part of the atmosphere and dramatised the photographs a lot, maybe over-stylised them a bit." He admitted his style of photography was gone forever. "Nobody smokes anymore."

Herman Leonard, photographer: born Allentown, Pennsylvania 6 March 1923; married 1960 Jacqueline Fauvreau (one daughter, marriage dissolved); one son with Attika Ben-Dridi; one daughter, one son with Elizabeth Braunlich; died Los Angeles 14 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments