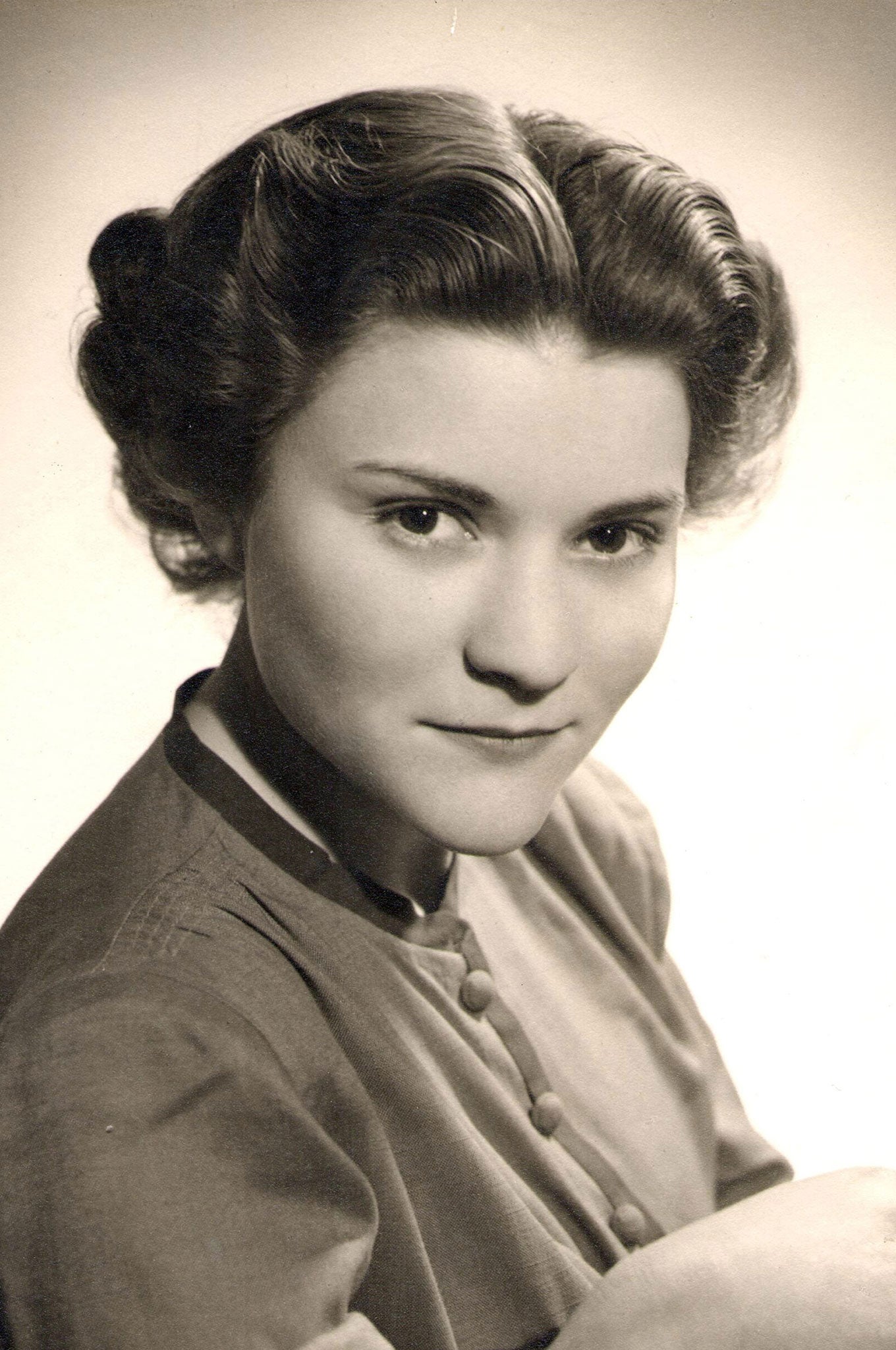

Helen Bamber: Psychotherapist who for seven decades worked in nearly 100 countries helping the victims of government torture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Helen Bamber, the psychotherapist and human rights activist, described torture – which she fought against in almost 100 countries during a work span of close on 70 years – as an attempt to kill a person without their dying. During a long life devoted to remedying the impact state-authorised torture had on the spirit as well as the body of victims, Bamber ended her life knowing that she had done more than probably anyone else in Britain – possibly the world – to put healing balm on to the aching scars of thousands of men, women and children.

Soon after treating two prominent Zimbabwean journalists, Mark Chavanduka and Ray Choto, who had been tortured over a 12-day period at an army detention camp outside Harare in 1999 after their paper, the Independent Standard, had published a story about an army officers’ attempted coup against Robert Mugabe, Bamber gave an interview with the journalist Fred Bridgland.

“I’ve discovered that people can overcome the most appalling tragedies,” she said. “They have their strengths, coping mechanisms and humour. But they need recognition and compassion from others if they are to survive and overcome their pasts. I’m not without my desolation and despair from time to time because it’s pretty rotten out there. But mostly I find listening so rewarding and humbling. In the end, I’m always inspired by the beauty of the human spirit.”

She added: “For me, torture is about total helplessness and total power, the deliberate destruction of people. I want more understanding of why we carry violence within us that, given certain opportunities, spurts out into cruelty. We’ve conquered so much in the 20th century in terms of medicine and science but we’ve learned relatively little about ourselves – and we are very cruel beasts.”

Before he returned to Zimbabwe – where he carried on attacking Mugabe until death silenced him in 2001 at the age of 34, Chavanduka told me, “Without Helen’s care, concern and love I would never have been able to carry on after what happened to me in Zimbabwe.”

Cruel beasts prowl the corridors of power, and they are everywhere. Bamber first learned that at the end of the Second World War when she had just turned 20 and went to Germany to help 20,000 or so survivors –most of them Jews at Bergen–Belsen, which was liberated by British soldiers in April 1945.

Her childhood prepared her for what she saw there. She was the daughter of Jews whose origin was the pogrom-infested Poland of the 19th century, When she was a girl growing up in Amhurst Park, a popular Jewish area of north-east London, her father read extracts from Hitler’s Mein Kampf to her. “He wanted,” she said later, “to underline the issues that were at stake for Jews around the world.”

Completing her secondary education at private Jewish school, she was determined to do something useful, and volunteered to join a team of British doctors to help survivors of the Nazi camps in Europe. “My father accepted this, almost with a shrug of resignation, “ she said. “I think it was something about repaying a debt. I was aware that if the Nazis had succeeded in invading England, we would have been the victims.”

In 1946 she returned to England, where she worked with the Jewish Refugee Committee, and was appointed to the Committee for the Care of Young Children from Concentration Camps. After meeting Anna Freud she trained to work with disturbed young adults and children and took a degree in Social Science at the London School of Economics.

In 1947 she married Rudi Bamberger, a German Jewish refugee from Nuremberg whose father had been beaten to death during Kristallnacht in Germany in November 1938. He anglicised his name to Bamber.

Helen went on to become a founding member of the National Association for the Welfare of Children in Hospital, and in 1961 joined the recently formed Amnesty International and became chairperson of the British group. In recognition of her work, the British Medical Association established a working party on torture and she led ground-breaking research into government torture in Chile, the Soviet Union, South Africa and Northern Ireland.

In 1985 she set up the Medical Foundation for Care of Victims of Torture in rooms at the National Temperance Hospital in London, moving to Kentish Town two years later. There, doctors and nurses treated up to 3,000 patients a year from almost 100 countries. Sometimes therapy consisted of sitting and listening and understanding the relief provided to victims of brain-battering torture techniques.

At the age of 80, she set up the Helen Bamber Foundation, and this continues to receive almost 1,000 referrals every year.

Honours came her way; she was awarded the OBE in 1997. She takes to the grave the certain knowledge that she helped so many people on this side of despair to live, work, and perhaps even love again.

Helen Balmuth, psychotherapist and human rights activist: born London 1 May 1925; OBE 1997; married 1947 Rudi Bamberger (Bamber) (marriage dissolved; two sons); died London 21 August 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments