Harrison Dillard: US track luminary who won four Olympic gold medals

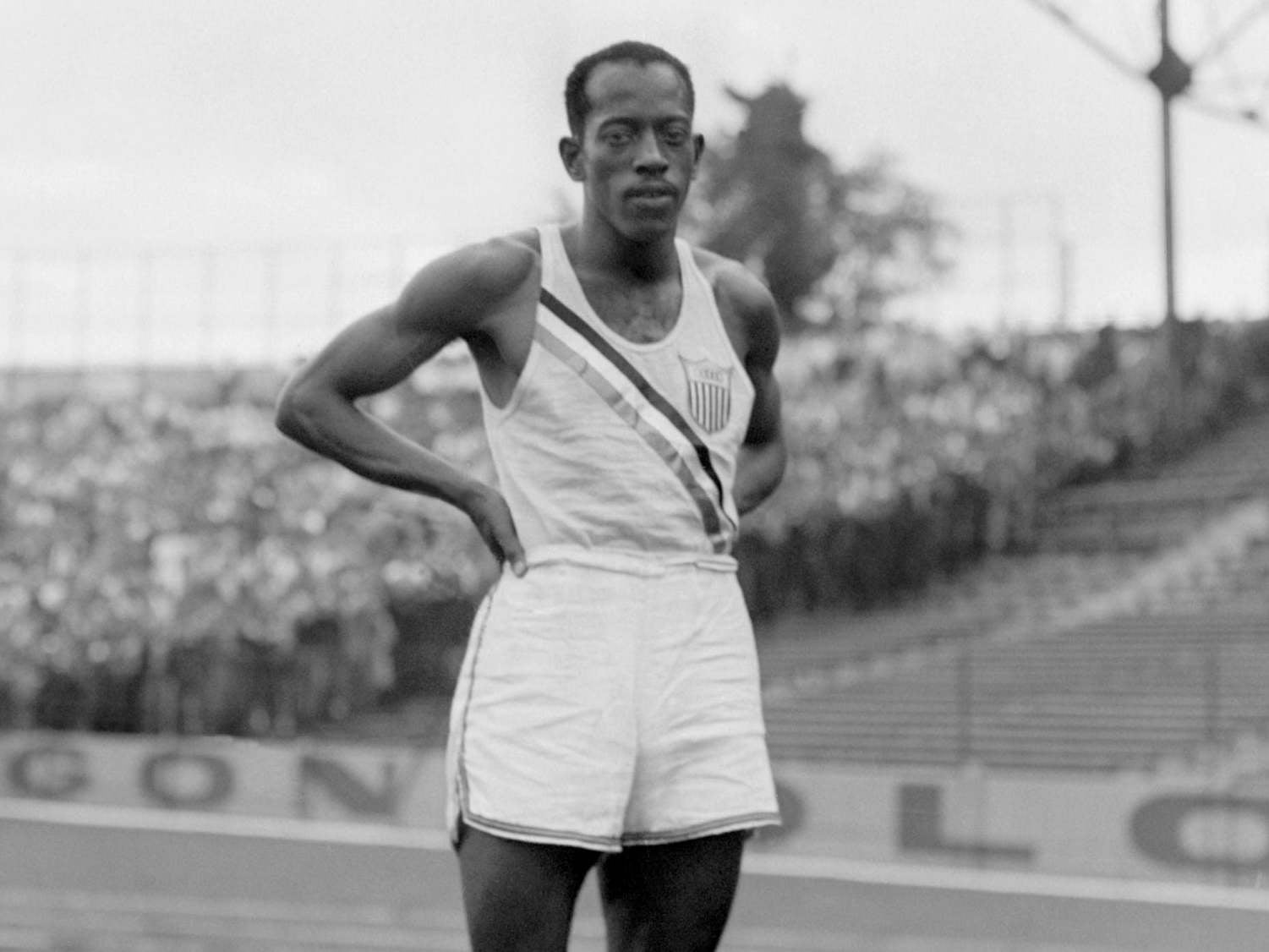

America’s oldest living gold medallist, Dillard modelled himself on Jesse Owens and eventually matched his idol

When Harrison Dillard lined up at the 1948 US Olympic trials in Evanston, Illinois, he had hoped to follow in the speedy footsteps of his Cleveland hometown idol, track-and-field star Jesse Owens, whose prowess at the 1936 games in Berlin brought him four Olympic gold medals and a lifetime of athletic renown.

Dillard – nicknamed “Bones” for his slight build – had been a standout track star in college, and his participation in the post-Second World War “GI Olympics” in Germany after his army service had left Gen George S Patton in awe. Although an excellent sprinter, Dillard had already set world records in hurdling in the mid-1940s, and that discipline, he thought, held the most promise for him to imitate the groundbreaking path of Owens. But he lost his stride in the 110m hurdle race that day in Evanston, striking several hurdles and failing to complete what he considered his showcase event.

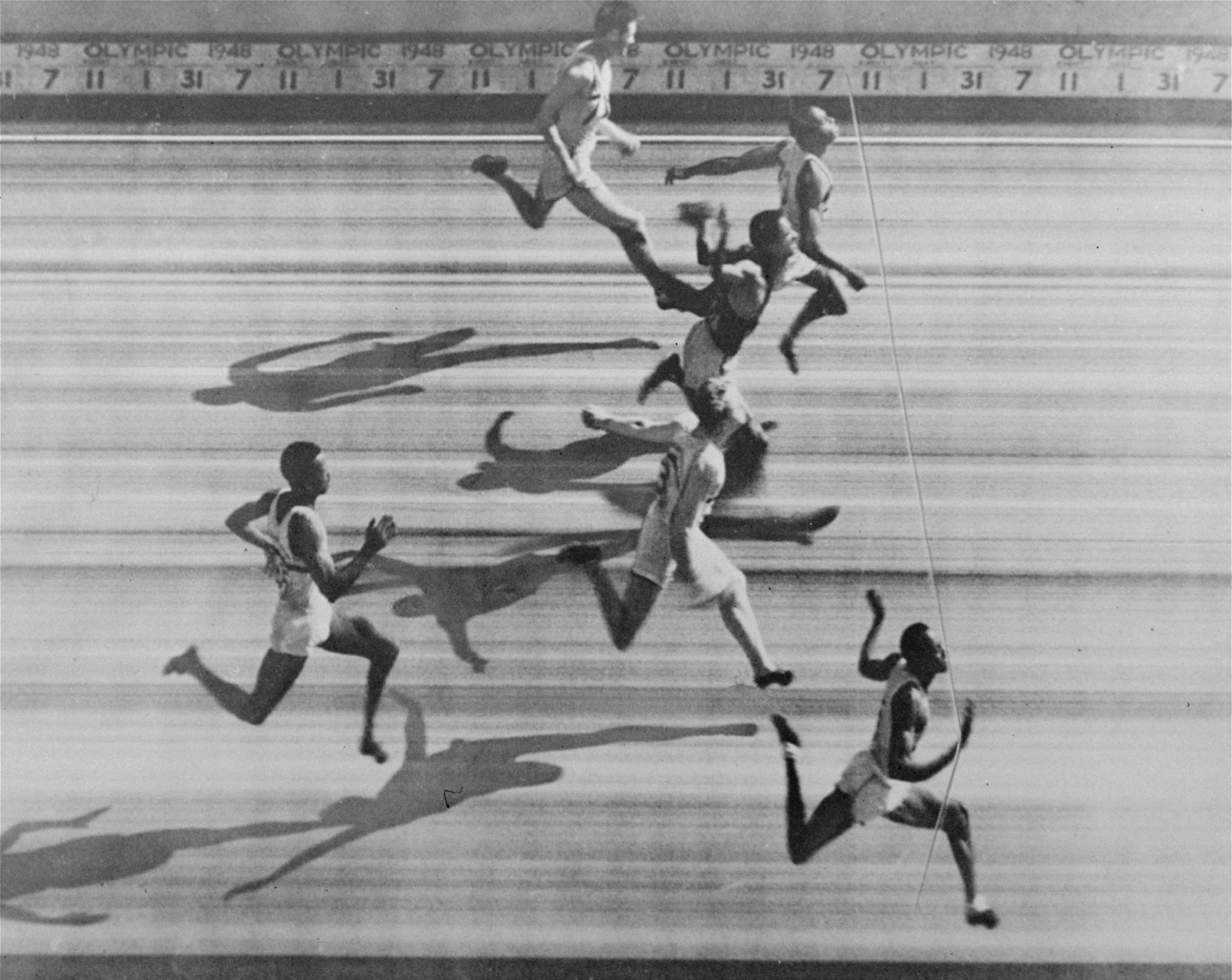

Instead, Dillard would go on to represent his country in the 100m sprint at the 1948 Summer Olympics in London, after qualifying for the race by finishing third in the trials. He had often discounted the event, thinking he was too slow. But in a photo-finish upset, he won Olympic gold. He also ran a leg as a member of the gold medal-winning 400m relay team.

Four years later, while competing in the games in Helsinki, he won gold in the 110m hurdles, becoming the only man to win Olympic gold as a sprinter and hurdler, a triumph that led him to match Owens for wins.

Dillard, who has died of stomach cancer aged 96, was one of the most dominant runners of his generation and was the oldest living US Olympic champion. During the 1952 Summer games in Helsinki, Dillard finally won the race he was expected to dominate – the 110m hurdles in an Olympic-record time of 13.7 seconds. He added another gold that year as a member of the 400m relay.

William Harrison Dillard was born in Cleveland in 1923. His father sold ice and coal door-to-door from a horse-drawn wagon, and his mother was a housemaid. Throughout his teenage years in Cleveland, Dillard and his friends took the seats out of abandoned cars and raced up and down the streets, using the spring frameworks as hurdles to mimic Owens, who grew up in the same neighbourhood.

In summer 1936, Dillard, then 13, watched a victory parade for Owens, whose four golds in Berlin brought embarrassment to Adolf Hitler. Dillard positioned himself close enough that he could touch Owens’ car. As the star passed by, he gave Dillard and the boys from the neighbourhood a wave and winked at them. Filled with excitement, Dillard sprinted home, determined to be just like him.

Dillard connected with Owens again in 1941 while preparing for the state championships his senior year at Cleveland’s East Technical High School, which Owens also attended. While chatting, Owens noticed that Dillard’s spikes looked a little worn. He gave Dillard a new pair of shoes. “I won the state championship in those shoes,” Dillard said later.

Dillard competed at Baldwin-Wallace College in nearby Berea, Ohio, becoming the first person in his family to attend college. As a sophomore, he helped the team to win the Ohio Athletic Conference championship for first time. But just as his trajectory as an athlete seemed assured, he was drafted into the army during the Second World War for service in the all-black 92nd Infantry Division, known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

After the war ended in 1945, the 5ft-10in, 150lb Dillard competed in a “GI Olympics” in Germany and won four events: the 200m dash, high and low hurdles and a sprint relay.

Dillard returned to college and won 82 consecutive races between 1946 and 1948, the longest winning streak in the history of major track competition until 400m hurdler Edwin Moses broke it in the 1980s. Dillard held several world records, including in the 220yd low hurdles (an event no longer seen in competition). In April 1948, he set a world record in the 120yd high hurdles, with a time of 13.6 seconds.

From 1949 to 1958, he worked for the Cleveland Indians, writing promotional material and making public appearances for the baseball team. Later in life, Dillard sold life insurance, worked as a Cleveland radio programme director and on-air personality, and wrote a sports column for the now-defunct Cleveland Press. In the 1980s, he was a sprinting instructor for the New York Yankees during spring training. He also spent 27 years as a business manager in the Cleveland public school system, as his public profile grew dimmer.

In his memoir, Dillard spoke of hurdling as a metaphor for the gritty determination that defined his ambition as a child growing up in Cleveland. “The other kids didn’t have the willingness, and they knew that the event was called ‘hurdles’ for a reason,” Dillard wrote. “They knew they’d most likely hit them, trip over them, crash to the track over them, and get scratched, get scarred and bleed. They weren’t willing to do that. I, however, was.”

He was married to Joy Clemetson, a softball player on the Jamaican national team, from 1956 until her death in 2009. He is survived by a daughter.

Harrison Dillard, athlete, born 8 July 1923, died 15 November 2019

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks