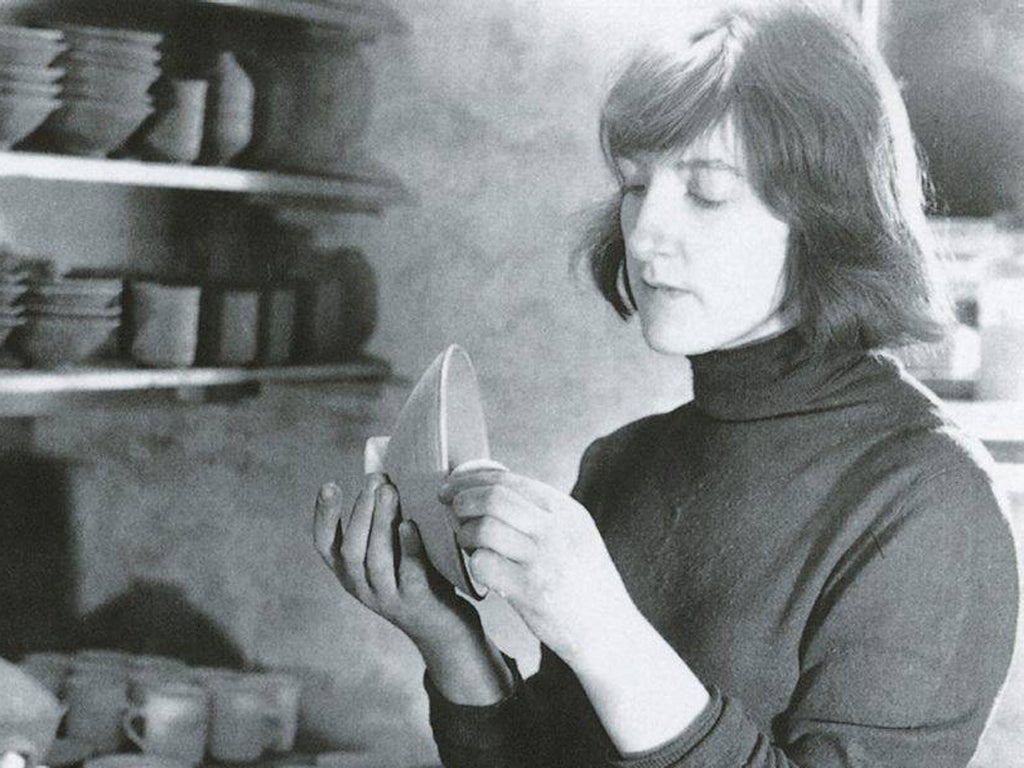

Gwyn Hanssen Pigott: Potter whose work was acclaimed for its clarity and calmness

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Gwyn Hanssen Pigott was a major figure in the field of international studio ceramics, whose work was characterised by its clarity and calm. From the mid-1980s she began to group apparently functional wares, in the form of bottles, beakers, cups and bowls, into sculptural still-life sequences of timeless purity, a move in the direction of fine art, seen at its most ambitious in her 55ft installation Caravan, shown at Tate St Ives in 2004.

Born Gwynion Lawrie John in the Australian mining town of Ballarat, she was the second of four sisters. Her upbringing was both strict and privileged. Her father, of Welsh descent, was the director of a large engineering firm while her mother, who had trained as an arts and crafts teacher, worked in an eclectic range of media.

Gwyn attended the University of Melbourne, where she majored in art history and paid regular visits to the National Gallery of Victoria. There, she became fascinated by the Kent collection of Chinese ceramics, "these seductive objects" as she called them. She met the first Australian exponent of stoneware, Harold Hughan, who introduced her to Bernard Leach's A Potter's Book, which greatly influenced her, and wrote her final-year thesis on contemporary Australian ceramics.

When she met Ivan McMeekin, an artist and potter, she realised (to her father's dismay) that she wanted to devote her life to ceramics. McMeekin and his young apprentice embarked on an exploration of local materials as they sought to create the dense, almost porcellaneous, qualities of Sung wares through raw glazing and wood firing. She translated the letters of the Jesuit priest Père d'Entrecolles on porcelain manufacture in early 18th-century China, and with McMeekin pored over AD Brankston's Early Ming Wares of Chingtechen. It might seem like a strange life for a young woman in her early twenties but it was a time of intense happiness.

In 1958 Gwyn arrived in England, took part in the first Aldermaston march in protest against nuclear weapons, and rode a bike to all the major ceramic workshops, working at Winchcombe Pottery with Ray Finch, discussing oriental ceramics with Sir Alan Barlow, visiting the potter Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie, working at the Leach Pottery at St Ives, where she met her future husband, the Canadian poet Louis Hanssen, and assisting Michael Cardew with his historic summer course Fundamental Pottery with an emphasis on geology and raw materials. In 1960 she set up a pottery in west London, teaching her husband Louis to make pots, working for Alan Caiger-Smith and attending classes given by Lucie Rie at Camberwell School of Art. Both Gwyn and Louis exhibited to acclaim at Liberty, at Heal's and at Primavera, London's premier craft and design shop.

In 1964 she bought a house in Achères, near Bourges, inspired by the traditional stoneware of the Haut-Berry area. She had worked at Cardew's Wenford Bridge Pottery during 1964-65 and was now committed to wood-firing and digging her own clay. Her long apprenticeship was over and in France she went on to make some of the finest functional stoneware and porcelain of all time. But in 1973 she walked away from her rural idyll and a varied teaching career.

She briefly worked with the Bread and Puppet Theatre in Vermont, returning to Australia in 1974, setting up a pottery in Tasmania and marrying her assistant John Pigott in 1976. By 1980 she was working in the Jam Factory Workshop in Adelaide (a difficult period when she considered abandoning ceramics) and in 1981 she moved to Brisbane as potter-in-residence at Queensland University of Technology where she also taught for the Australian Flying Arts outreach programme, travelling in small planes all over Northern Queensland. In 1989 she moved to Netherdale, a sub-tropical sugar-cane region west of MacKay in northern Queensland, and in 2000 set up her final pottery near Ipswich in south-east Queensland.

From 1972 onwards many of her decisions were informed by her commitment to the teachings of Prem Rawat, known as Maharaji. This created a global network of friends but by the early 1990s she was also exhibiting worldwide and constantly travelling. In 1971 she had been profoundly affected by a large retrospective exhibition of paintings by Giorgio Morandi at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

In the early 1980s she was using the Japanese-Korean potter Heja Chong's noborigama kiln, a method of firing in which glaze is redundant. New shapes seemed required, memories of Morandi floated up, and she began making bottle forms that were to develop into the still-life assemblages for which she became renowned. Their matchless beauty and haunting titles led to invitations to create similar atmospheric groupings using pots from the oriental ceramics collections at the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington (2008) and, subsequently, objects from the ethnographic collections at the Museum of Anthropology, Vancouver (2012).

In 2002 she was awarded the Order of Australia Medal and in 2006 the National Gallery of Victoria staged a major retrospective of her work. At the time of her death she had plans to work in Japan and Spain and to show her work at Chatsworth House, Derbyshire.

Gwyn remained loyal to her first husband Louis Hanssen (who committed suicide in 1968 and whose later life was the subject of Nicholas Wright's 2007 play The Reporter) and to her second husband John Pigott, from whom she separated in 1980.

Hanssen Pigott died of a stroke. The last few weeks of her life, spent in Europe, were crowded with visits and reunions, culminating in a marvellous solo exhibition in London that showed the artist at the height of her powers.

Gwynion Lawrie John, potter: born Ballarat, Victoria, Australia 1 January 1935; married firstly Louis Hanssen (marriage dissolved, deceased), secondly John Pigott (marriage dissolved); died London 5 July 2013.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments