Gordon Willis: Cinematographer and low-light maestro who shot the 'Godfather' trilogy and made nine films with Woody Allen

The cinematographer Gordon Willis was jocularly known as "The Prince of Darkness" for his experiments in low-light photography, pushing film to the limits but always retaining just enough detail. Sometimes the shadows are lustrous and inviting, and sometimes threatening. Nevertheless, he insisted that there was no formula to his work ("the formula is me"). His best-known work was for directors as various as Francis Ford Coppola (the Godfather trilogy), nine films with Woody Allen and Alan J Pakula's classic 1970s paranoia thrillers, but he also shot several comedies.

Willis came from an entertainment family: his parents were Broadway dancers, though his father sidestepped into the film industry to become a make-up artist at Warners. Willis considered acting before turning to stage design and lighting for summer stock companies and then trying to break into fashion photography by shooting Greenwich Village neighbours' model portfolios. But as he later recalled, he "didn't know shit […] dumber than dirt, as they say." Eventually his father got him work as a gofer on some film productions.

He joined a documentary film unit in the Korean War, learning a great deal from David L Quaid, who later shot some feature films less distinguished than Willis's. In particular he developed his stripped-down, minimalist style. Demobbed, Willis started as an assistant cameraman, though "I was still dumber than dirt". Thirteen years later he finally became a first cameraman. His first effort was a 1970 adaptation of John Barth's counter-culture black comedy novel End of the Road. Unsurprisingly, with Terry Southern as one of the co-writers, it hit problems, particularly with the abortion scene. Nevertheless, it led to more assignments for Willis.

The same year he shot Hal Ashby's first film, The Landlord, a comedy in which a would-be rapacious landlord turns into a liberal. He would have worked with Ashby more (despite the director's drug problems) but union rivalries and other projects intervened.

The often nocturnal Klute (1971) in which a detective and a prostitute collaborate to find a missing man, marked Willis's first collaboration with Alan J Pakula, and he went on to shoot the rest of the director's unofficial "paranoia trilogy". In The Parallax View (1974) a reporter stumbles upon an organisation that arranges a series of political assassinations. The surveillance element of the story was reflected by Willis's use of telephoto lenses and the resultant shallow depth of field, odd framing and blocked points of view. All the President's Men (1976) dramatised the Washington Post investigation into Watergate.

Willis's only western (albeit set in the 1940s) was Pakula's Comes a Horseman. They rejoined for the financially successful thriller Presumed Innocent (1990) and Pakula's last film, the simplistic IRA action-drama The Devil's Own (1997).

Willis gave The Godfather (1972) a period feel by shooting it "in a tableau fashion. That meant no zoom lenses, no helicopters and no contemporary film devices." However, Paramount was expecting a more conventional gangster film, and their harassing of Coppola made shooting it "like trying to serve a sit-down dinner on the deck of the Titanic."

Willis simply put his head down and drove on, concentrating on "how-to" conversations with Coppola; Brando's make-up necessitated distinctive overhead lighting. For the flashbacks in The Godfather II (1974) Willis kept the colour palette but changed the shooting style to mark a difference without pulling the audience out of the film. Willis returned in 1990 for The Godfather III.

He shot nine films for Woody Allen, several in black and white, from Annie Hall (1977) to The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). It was so easy, he said, that it was like "working with your hands in your pockets."

Annie Hall was shot over 10 months with scenes being developed, sometimes in response to discovered locations, and some post-editing re-shoots. Thematically and visually chilly, Interiors (1978) is Allen's most Bergmanesque film. For Manhattan (1979), they agreed that New York was "a black-and-white city", though most of Allen's other New York pictures are in colour. Unusually, even before widescreen televisions, Allen insisted that video releases retain Willis's compositions rather than being pan-and-scanned, making it one of the few early letter-boxed releases.

Zelig (1983) is Allen's most visually complex film, interweaving colour "contemporary" footage with genuine black-and-white newsreels and re-enactments made to match. Pre-CGI, this was achieved very simply by using old cameras and physically damaging the film stock.

Willis directed one film, Windows (1980) a queasy lesbian peeping-Tom drama that he later regretted, if not for the subject, at least for the fact that he simply preferred shooting to directing and having actors "call me up at two in the morning saying 'I don't know who I am.'"

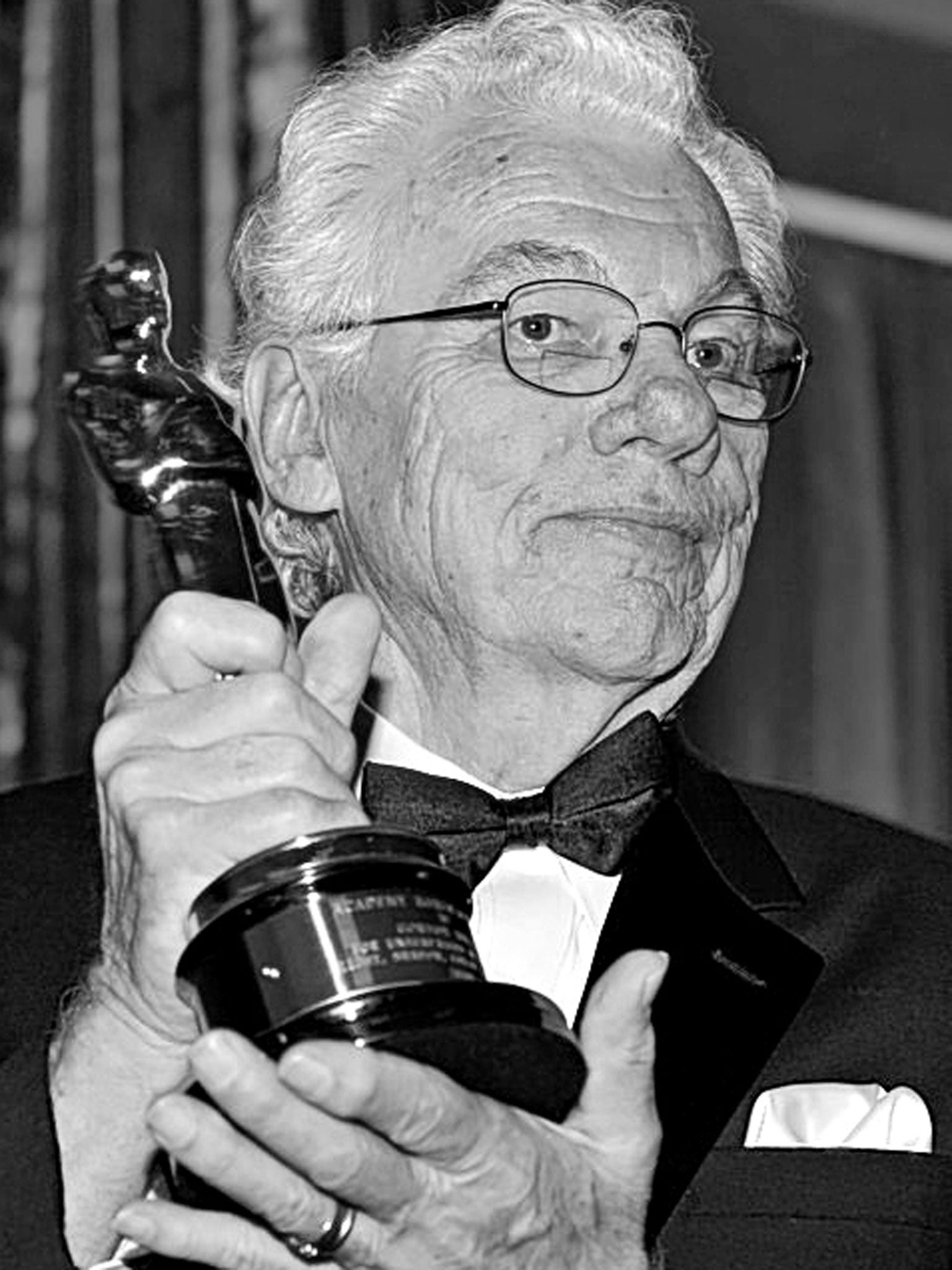

In later years he shot lighter fare, including The Money Pit (1986) and The Pick-Up Artist (1987) Though some of his most ground-breaking work was in the 1970s, Willis had to wait until Zelig for an Oscar nomination, with another for The Godfather III, though he was pipped for both. Some thought this was in part due to his gruff manner ("I'm not that easy to deal with") and dismissal of Hollywood ("I don't think it suffers from an over-abundance of good taste"). The Academy's only recognition was an honorary award in 2009.

Not one to look back, Willis agreed that The Godfather was "one of the better films ever made", but said: "sometimes I go back and look at one I haven't seen for years and discover it's a much better film that I thought when I was shooting it. That's always a pleasant surprise."

Gordon Hugh Willis, Jr, cinematographer: born Astoria, New York 28 May 1931; died North Falmouth, Massachusetts 18 May 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks