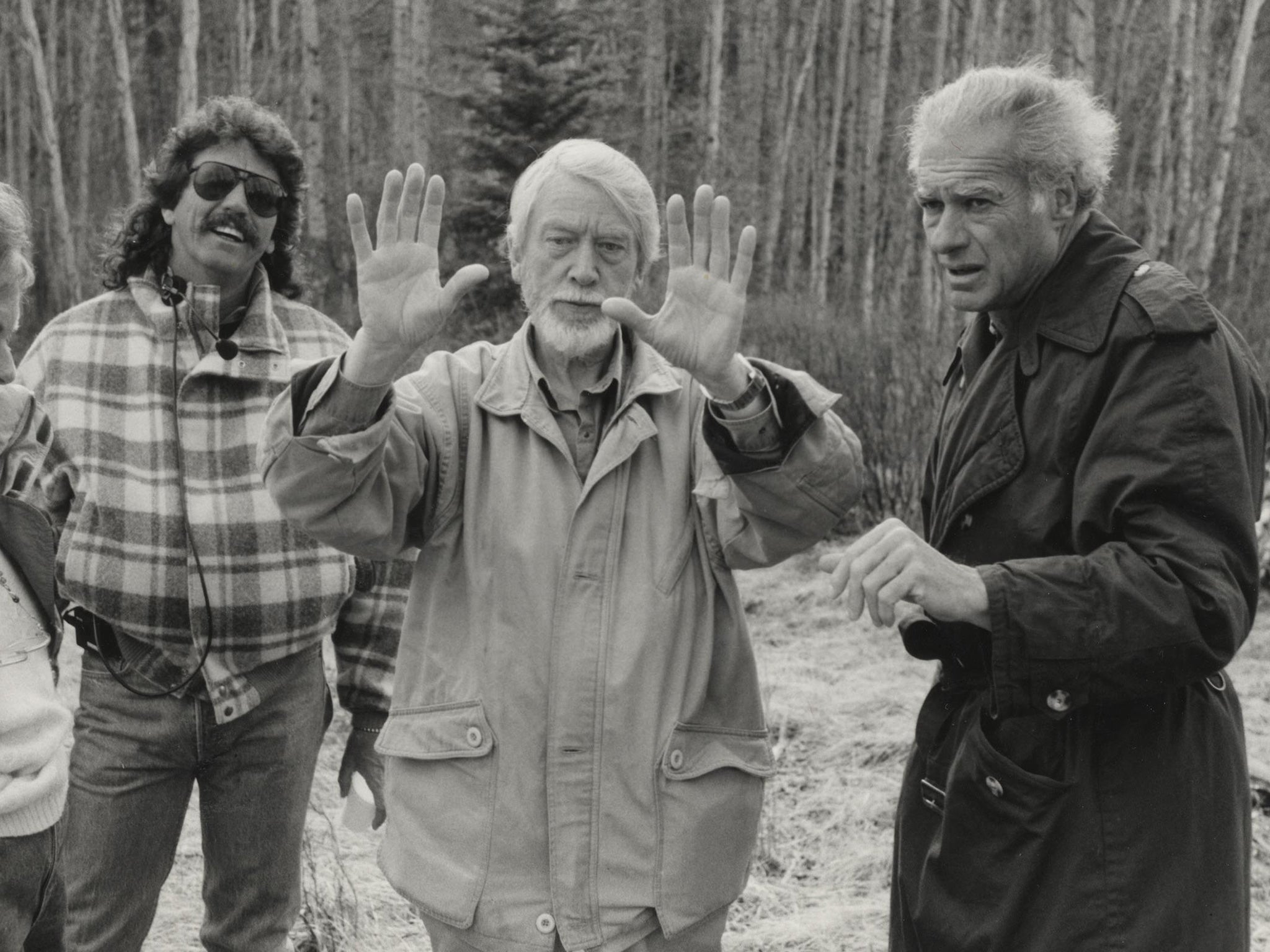

Gerry Fisher: Prolific cinematographer who worked with some of the finest directors of his day - most profitably, Joseph Losey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Gerry Fisher was one of Britain’s finest cinematographers, responsible for the look of more than 60 films, most illustriously with director Joseph Losey.

He went up the ranks from camera operator to director of photography when he shot Losey’s Accident (1967), a Harold Pinter adaptation of Nicholas Mosley’s novel, starring Dirk Bogarde as a married Oxford University professor going through a mid-life crisis as he pursues a student whose fiancé has died in a car crash. Fisher succeeded in lighting interior and exterior scenes to get moody shots reflecting the dark, pessimistic themes of the film while battling days of torrential rain over the summer of 1966.

He showed his versatility by creating a completely different, “bright” look for The Go-Between (1971), the third of Pinter’s collaborations with Losey, which started with The Servant in 1963 and were incisive in their exploration of the moral bankruptcy and thwarted desires among the English middle and upper classes.

Based on L P Hartley’s Edwardian novel about a boy who acts as messenger for a tenant farmer and his friend’s elder sister, who is married to a wounded Boer War veteran, The Go-Between starred Alan Bates and Julie Christie as the lovers conducting a passionate affair during a long, hot summer. With scenes of croquet, cricket matches and picnics, large rooms and echoing corridors, Fisher’s photography reflected the essence of the English countryside of summers long ago.

Alongside the nostalgic look, he was challenged by Losey to make 30-year-old Christie appear like the teenage heroine of the novel. “I was asked, could I make Julie Christie look 18?” Fisher told me in 1999. “My response was, ‘If you give me carte blanche so that each shot of her is entirely controlled to that purpose, it’s conceivable. She could pass as 18 provided she could play 18. But, if you think I can make Julie Christie appear 18 and others look the age they are, with her taking tea round to people sitting at tables on the lawn on a summer’s day, then no’.

“I’m very proud of the film. In many ways, it reflected my own childhood. In the long, hot summers, out of school, I would go to the fields and lie flat on my back in the corn and hear field mice and birds, and get the heat near the ground. I was very aware of that and tried to bring some of that feeling to the photography.”

Fisher was born in London, the son of Oliver, an actor, and his wife, Margaret (née Maule-Eyles). On leaving technical college, he had jobs for Kodak and the De Havilland Aircraft Company before Second World War service in the Royal Navy. In 1946, he broke into the film industry as a clapper boy at Alliance Riverside Studios, then worked as a camera assistant on documentaries for Wessex Films and, from 1947 at Shepperton Studios, on feature films, beginning with They Made Me a Fugitive (1947).

A couple of dozen pictures, including An Inspector Calls (1954) and A Kid for Two Farthings (1955, for director Carol Reed), followed in this capacity – and Fisher was focus-puller on several more – until he was promoted to camera operator for David Lean’s classic The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957).

His reputation grew as he shot another 20 films, including The Millionairess (1960), The Sundowners (1960), The VIPs (1963), Cleopatra (1963), Night Must Fall (1964) and Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965) for top directors such as Guy Hamilton, Anthony Asquith, Joseph L Mankiewicz, Karel Reisz and Otto Preminger, and leading directors of photography Christopher Challis, Geoffrey Unsworth, Freddie Francis and Douglas Slocombe.

The list of Hollywood stars in front of his lens included Burt Lancaster, Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, Peter Sellers, Robert Mitchum, Peter Ustinov, Bing Crosby, Bob Hope, David Niven, Charlton Heston, Albert Finney, Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Deborah Kerr, Katharine Hepburn, Sophia Loren, Ava Gardner, Ingrid Bergman and Shirley MacLaine.

Fisher was also camera operator on Modesty Blaise (1966) for Joseph Losey, who asked him to take over responsibility for one scene in Amsterdam when his director of photography, Jack Hildyard, refused to shoot it because of poor light.

Later, when Fisher was working on the James Bond spoof Casino Royale (1967) in Ireland, Losey asked him to read the script for Accident and let him know whether he could shoot it as director of photography. “I began to read a script for the first time in terms of what I would do with it, of the way I visualised it,” recalled Fisher. “So it fell into place, it suggested itself to me in terms of images, of how I felt it should look.” Fisher left the Casino Royale shoot and made his debut as a cinematographer, with Accident winning the Cannes Film Festival’s Grand Prize of the Jury.

He also worked with Losey on Secret Ceremony (1968), A Doll’s House (1973), The Romantic Englishwoman (1975), Mr Klein (1976), Les Routes du Sud (Roads to the South, 1978) and Don Giovanni (1979). The Go-Between won the Palme d’Or, the top prize in Cannes.

Fisher’s many other films as director of photography included Ned Kelly (1970) for Tony Richardson, The Offence (1972) and Running on Empty (1988) for Sidney Lumet, Butley (1974) for Harold Pinter, Juggernaut (1974) for Richard Lester, The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother (1975) for Gene Wilder, Aces High (1976) for Jack Gold, Fedora (1978) for Billy Wilder and Wise Blood (1979) and Escape to Victory (1981) for John Huston. He ventured into horror with Blind Terror (1971, starring Mia Farrow) and fantasy with The Island of Dr Moreau (1977) and Highlander (1986).

Known by all who worked with him as a well-dressed English gentleman who drank champagne, Fisher particularly enjoyed filming in France. He made half a dozen pictures there, including his last, Furia (1999), before retiring at the age of 73. In 1997, he was made a Chevalier dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Knight in the Order of Art and Literature). Eleven years later, he received a British Society of Cinematographers Lifetime Achievement Award.

Fisher’s wife, Jean, died three days before him. Their son, Cary, became a film camera operator himself and was director of photography for the television series CSI: NY.

Gerald Fisher, cinematographer: born London 23 June 1926; married 1951 Jean Hawkins (died 2014; one son); died Reading, Berkshire 2 December 2014.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments