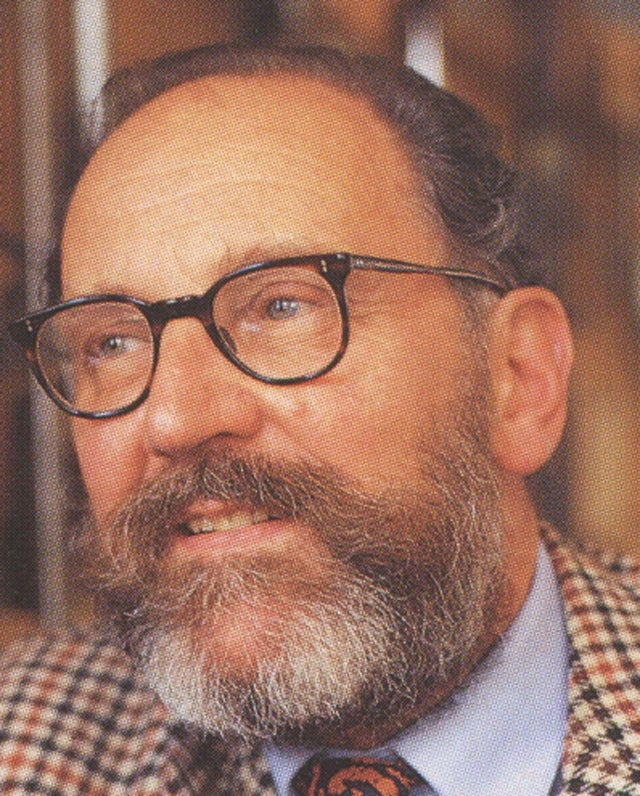

Gerald Benney: Distinguished goldsmith

Gerald Benney was one of the most outstanding and influential British goldsmiths of the second half of the 20th century. During a career spanning more than 50 years, he was the first British craftsman to hold four Royal Warrants simultaneously. His work has had a major impact on the survival of domestic silver in Britain.

From 1946 to 1948, Benney trained at Brighton College of Art, where his father was Principal. He was taught there by Dunstan Pruden, the Roman Catholic ecclesiastical arts and crafts silversmith, and a member of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic near Ditchling on the South Downs, founded by Eric Gill. At this period, the young Benney's work was initially influenced by the arts and crafts style of his teacher and later, for a brief period, by pre-Second World War modernism.

After military service, from 1948 to 1950, Benney studied at the Royal College of Art. In 1952, a four-piece tea service and tray secured him the Prince of Wales Scholarship. In his last term at the RCA he purchased a plating business off Tottenham Court Road, as the premises were ideal for a workshop. He persuaded the proprietor to stay to run the business for three years as a financial buttress for his fledgling commercial silversmithing enterprise.

During the 1950s, young designers and silversmiths sought to create pieces that were totally new and identifiable as being of their time. In his early years, Gerald Benney was no exception, and he was influenced by the purity and minimalism of Scandinavian design. For him this translated into a range of domestic silver notable for its clean, simple lines.

By the early 1960s, the style of Gerald's work became instantly recognisable as "Benney". His designs have strength and dignity, an aura of splendour without ostentation. Indeed, his work is dramatic because of its simplicity and scale. The textured surfaces that have long been a feature of Benney's work first appeared on a piece of his silver at this time by accident. While hand raising the bowl of a cup – that is, taking a flat piece of silver, placing it over a variety of shaped stakes and hitting it steadily and consistently with hammers until the desired shape is achieved – he inadvertently used a hammer with a damaged head. After half a dozen blows, what should have been a smooth surface had a pleasing pattern imposed on the silver. Benney filed the hammer's head to emphasise the pattern and continued the experiment.

Pleased with the result, he produced beakers and goblets to test his invention. Not only did texturing work technically and aesthetically, it also became a valued and unique expression of his skill on his own work. Emulation is said to be the highest form of flattery. It was not long before a large part of the industry was imitating what became known in the trade as "Benney Bark Finish".

Clearly, texturing looks good and in its early days, being regarded as an artistic novelty, the style certainly boosted sales. It soon became apparent that there was a practical advantage too. Handle silver with a polished surface and fingerprints immediately appear. These marks, which are caused by moist skin, also cause tarnishing. However, with Benney's texturing, the fingers do not press continuously on to the metal's surface, just the textured high points, and marks are not visible.

Although renowned for his domestic silver, Benney was also an outstanding box maker. Although he made boxes from the 1950s onwards, it was in the mid-1960s that he started a range that added new dimensions to the genre. Always of good gauge, the sides invariably bear his distinctive bold texturing. That is, however, where their uniformity ends. The patterns on the surfaces of the lids were skilfully tapped in with a chasing hammer, and colour, in the form of 18-carat gold, was usually added to the surfaces.

In the late 1960s Benney noted a revival of interest in objets d'art. Feeling that his work needed colour, he decided that it was time for enamelling to blossom again. He therefore journeyed to Zurich to search for craftsmen who had worked for Burch-Korrodi, the last well-known firm of fine enamellers. Burch-Korrodi had obtained some of his skills from Fabergé's craftsmen. While walking along the city's main shopping street Benney slipped and sprained his ankle outside Türler's, the jewellers. Herr Türler came to his assistance. While Benney was recovering he revealed his mission. By chance, Türler knew Burch-Korrodi's head enameller, the Norwegian Berger Bergersen who had also worked for Bolin, a rival of Fabergé who had fled to Stockholm after the Russian Revolution.

Bergersen was persuaded to travel to England to advise on enamelling techniques. The slow process of reviving a virtually extinct craft began. Bergersen stayed for several months, teaching the team in Benney's workshop everything he knew. However, Benney naturally developed contemporary designs and managed to cover even larger surfaces than the House of Fabergé.

Benney also turned his attention to the mass markets. From 1957 to 1969 he designed stainless steel cutlery for Viners. His most popular design was "Studio" – it is still traded on eBay today. He negotiated a royalty payment as opposed to a flat fee, a very astute move.

In 1973, Benney's former professor at the RCA, Robert Goodden, was due to retire, and asked Gerald if he was interested in the post. While flattered by the invitation, Benney felt he would not have sufficient time for teaching, having recently undertaken some demanding new commissions. A compromise was reached, with the appointment limited to two days a week. Benney became Professor of Silversmithing and Jewellery, holding the chair until 1983.

The Benney workshop moved from London in 1974. However, 20 years later, Gerald's son Simon Benney opened a shop in Walton Street in Knightsbridge to retail both his own jewellery and his father's silver. Upon Benney senior's retirement in 1998, Simon also took over the silver side of the business. I last saw Gerald Benney in January when Simon unveiled a client's commission, "The Three Sisters" candelabra, at Goldsmiths' Hall. Weighing over 50 kilograms, it is the largest piece of silver to have been made in Britain for many years. Benney was quite rightly very proud.

Adrian Gerald Sallis Benney, goldsmith and silversmith: born Hull, Yorkshire 21 April 1930; Professor of Silversmithing and Jewellery, Royal College of Art 1974-83; CBE 1995; married 1957 Janet Edwards (three sons, one daughter); died Cholderton, Wiltshire 26 June 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks