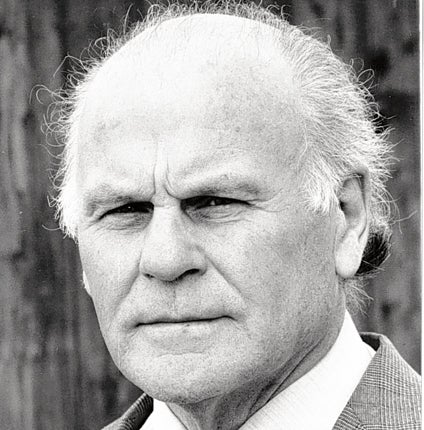

Geraint Bowen: Archdruid of Wales who campaigned against nuclear dumping and championed Welsh-language television

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Archdruid of Wales from 1979 to 1981, Geraint Bowen was renowned for his hard-hitting speeches from the Logan Stone in the ceremonies of the Assembly of Bards of the Isle of Britain (the Gorsedd). Not only did he speak out against the Anglicisation of Wales and in defence of the Welsh language, as Archdruids are expected to do, but also lent his authority to the campaign for a fourth television channel broadcasting in Welsh and against the burying of nuclear waste. In this he ran the risk of upsetting some of the more pusillanimous officers of the National Eisteddfod, to which the Gorsedd is closely affiliated.

He also called for unity among Celtic peoples and denounced the French government's intransigence towards the Breton language and the movement calling for a wider measure of Breton autonomy. His pan-Celtic sentiments were reported in the Parisian press and made him something of a hero among militant Bretons.

In 1977 he became editor of the Welsh-language weekly Y Faner, though he did not last long in that capacity. Understaffed, underfunded and housed in Dickensian offices at Bala in Merioneth, the paper was fast losing readers and Bowen's rather gruff editorials put many off. When the Arts Council insisted that the paper should make an effort to win new readers by carrying more popular copy, or lose its subsidy, the editor resigned. "I was not asked to edit a paper of that sort," he wrote contemptuously in his autobiography, O Groth y Ddaear ("From the womb of the earth", 1993), "and so I resigned after six months."

Some thought Bowen's outspokenness may have been a reaction against the restrictions of having been employed between 1961 and 1975 as a member of Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Schools. But that was to misunderstand the nature of the man and the forces that went to his making. Geraint Bowen was born in Llanelli, the former steel and tinplate town in Carmarthenshire, in 1915, and brought up in a strictly religious home at New Quay in Cardiganshire. His father, an ex-collier, was a minister with the Independents, or Congregationalists, always the most radical of the Welsh denominations, and one of his brothers was the poet Euros Bowen.

After attending the grammar school in Aberaeron, Bowen entered University College, Cardiff, graduating in economics and politics in 1938, and went on to Liverpool University, where he took an MA in Celtic. His doctoral thesis was on the literature of Recusancy, the Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation in south-east and north-east Wales, and on which he was to write extensively.

Bowen was a member of Plaid Cymru, and its candidate in the safe Labour seat of Wrexham at the 1950 general election. During the war he registered as a conscientious objector on Welsh Nationalist grounds and was ordered to work on the land. The poem with which he won the Chair at the National Eisteddfod in 1946, "Yr Amaethwr" ("The farmer"), drew from Thomas Parry, the foremost literary critic of the day, the comment that it was the most technically accomplished poem of the half-century.

It was based on one of the farmers who employed him, John Jones, a monolingual countryman of Blaen-cwm, Cwm Cynllwyd, in the Berwyn hills. The poet wrote of him: "Caled oedd fel clwydi og / A mwyn fel gofer mawnog." ("He was hard as a harrow's spikes and soft as newly cut peat.") The lines were written about my wife's grandfather but, for all his seriousness, fierce countenance, brusque manner and ultra-nationalist opinions, they might have applied to Bowen.

He published one slim volume of his own verse, Cerddi ("Poems", 1984), which received an Arts Council prize. He was a master of cynghanedd, the prosody in which much Welsh verse is written, particularly of the englyn, the four-line verse composed according to rules of devilish complexity.

Much of his life was given to scholarship. First he edited Gwasanaethy Gwyr Newydd by the Recusant Robert Gwyn, the most prolific Welsh writer of the Elizabethan age, whoalso wrote Y Drych Cristianogawl("The Christian mirror", 1586), the first book to be printed in Wales, which appeared in 1970. His last book was Ar Drywydd y Mormoniaid ("In search of the Mormons", 1999).

Despite his academic absorption in Welsh Catholic literature, Bowen was a forthright atheist. Some thought an over-pious upbringing had caused him to turn against religion, but it is more likely that his Yorkshire-born, Welsh-speaking wife, Zonia, militantly atheist, was a crucial influence. The appointment of an Archdruid who openly admitted he had no God caused consternation in neo-druidic circles and several members resigned in protest.

As an editor he was industrious and meticulous. He compiled three volumes on the Welsh prose tradition, as well as a collection of essays on Celtic civilisation. But his main achievement was a history of the Gorsedd of Bards, that bastion of the nation's literary and linguistic heritage founded by the brilliant forger Iolo Morganwg, which he wrote with his wife and published in time for its second centenary in 1992.

Geraint took his role as Archdruid seriously. In 1980 he led a deputation to Hallein, near Salzburg in Austria, one of the cradles of Celtic civilisation, for the opening of an exhibition entitled "Die Kelten in Mitteleuropa". He cut an imposing figure in his neo-druidic robes and was much feted as a living presence from "the enchanted woods of Celtic antiquity".

In 1980, when he was living on the shore of Tal-y-llyn in Merioneth, he became part of the campaign to prevent the burial of nuclear waste at various sites in southern Gwynedd and northern Powys. He served as chairman of Madryn, a movement with branches throughout the area, and presided over a policy of non-violent action against such bodies as the Forestry Commission and the Institute of Geological Sciences. which were searching for suitable sites.

Eventually successful, the campaign led to a famous declaration that Wales was "a non-nuclear country". It had the support of Dafydd Wigley, Neil Kinnock, AJP Taylor and Joan Ruddock, but it was Bowen's denunciation of Nirex, the Nuclear Waste Inspectorate, during the Eisteddfod of that year, which received most publicity. Few Archdruids can claim to have stopped Leviathan dead in its tracks.

Meic Stephens

Geraint Bowen, poet: born Llanelli, Carmarthenshire 10 September 1915; Archdruid of Wales 1979-81; married 1947 Zonia North (two sons, two daughters); died Bangor, Gwynedd 16 July 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments