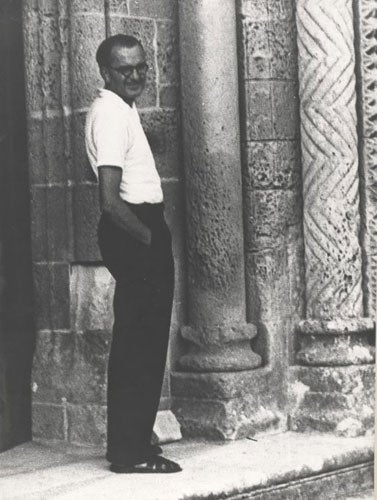

George Zarnecki: Former deputy director of the Courtauld Institute of Art and leading scholar of Romanesque sculpture

George Zarnecki was a leading scholar of medieval art whose authority in the field of English Romanesque sculpture has remained unchallenged over half a century. In his role as deputy director of the Courtauld Institute of Art at the University of London, he was revered by generations of students.

Zarnecki was born in Stara Osota, then in Russia, now in Ukraine, to a Polish-speaking family, his father a convert from Judaism, his mother Catholic. He obtained his MA degree at Krakow University in 1938 and became a junior assistant in the Art History Institute.

Zarnecki's career was interrrupted by the outbreak of war. He joined the Polish army, serving in France, where he was taken prisoner in 1940 and only just escaped being sent to a concentration camp after being denounced as a Jew. What saved him was the fact that the Germans' inspection showed that he was not circumcised, and also that his mother had given him a crucifix to wear under his shirt.

He escaped with the help of forged documents in 1942, spent time in occupied southern France, and after being interned in Spain, escaped to England. There, still in the Polish army, he met Anne Leslie Frith, who became his wife and lifelong support. They met during an air raid, while taking shelter at Regents Park tube station in 1944. Seeing him, Frith was deeply impressed not only by his looks but by his splendid uniform. With all those braids and epaulettes, she thought, he must be a general. At which point in the story, George smiled and explained: "I was never more than a lance corporal." His war service was, later recognised by the award of the Polish Cross of Valour and the Croix de Guerre.

After the war he undertook a PhD at the Courtauld Institute under the inspiring supervision of Fritz Saxl, director of the Warburg Institute. Completed in 1950, the subject of his dissertation was the Regional Schools in English Sculpture in the 12th century and it set the course of his academic career.

In 1945 he had obtained his firstemployment at the Courtauld, asassistant in the Conway library, the unrivalled photographic archive of medieval art and architecture. Scholars in the field have owed much to Zarnecki's photographic campaigns abroad, which added considerably to the library's holdings.

After 10 years as Conway librarian, he joined the teaching staff with the rank of Reader in 1959, became deputy director in 1961 and Professor in 1963. It was a period of expansion for the Institute under Anthony Blunt's directorship and it was Zarnecki who carried the main administrative burden. His diplomatic and managerial skills were much admired and it was thought that he would become director when Blunt retired in 1974. But he felt that he wanted to return to more teaching and research and declined to apply.

His achievements as scholar and deputy director received recognition from the 1960s: most notably, he was elected Fellow of the British Academy in 1968, made CBE in 1970 and received several honorary doctorates. The Society of Antiquaries, of which he had been vice-president, was particularly close to his heart and he was touched to be the recipient of its gold medal in 1986. His generous help to Polish students and scholars was recognised by the award of several Polish distinctions.

Zarnecki published a considerable body of work which was both authoritative and accessible. His two volumes on English Romanesque Sculpture 1066-1140 (1951) and Later English Romanesque Sculpture 1140-1210 (1953) are deceptively modest in length and format. They were the first to propose a widely accepted structure of dates and sequence of the main monuments and they remain authoritative to this day. Due partly to the iconoclasm of the Reformation, relatively little remains of Romanesque sculpture in England when compared to Continental countries, but Zarnecki's two volumes served to demonstrate the emotional impact and international standing of many of the surviving monuments.

These general books were followed by detailed studies: English Romanesque Lead Sculpture (1957), Early Sculpture at Ely Cathedral (1958) and Romanesque Sculpture at Lincoln Cathedral (1963, expanded ed.1988), as well as numerous innovative articles collected in his two volumes of Studies in Romanesque Sculpture. Of his major publications, only Gislebertus: sculptor of Autun (1961) concentrates on a Continental monument.

The 11th century saw the revival of monumental architectural sculpture, of which there had been very little in the earlier Middle Ages, and most of the surviving sculpture of the period forms an integral part of ecclesiastical buildings large and small. Accordingly, a study of the history of the architectural setting was Zarnecki's first concern, followed by a close analysis of the sculpture itself. Comparisons, particularly with contemporary English illuminated manuscripts and Continental sculpture, were adduced to fix sources of inspiration, dates and sequences of development. And if stylistic analysis was the main concern, his expertise also covered questions of material, of patronage and iconography. One of his most valued early studies demonstrated that the Coronation of the Virgin, an image best known from 13th-century French sculpture and mosaics in Roman churches, in fact had its earliest development in England, as seen in a capital of c.1130 from Reading Abbey.

Shortly after retirement, Zarnecki achieved a particular triumph with the Arts Council's magnificent exhibition English Romanesque Art at the Hayward Gallery in 1984. His was the inspiration and expertise behind the exhibition which, for the first time, brought the subject to a really wide audience. Indeed, although his reputation is that of a specialist, his ability to cover large fields for a more general public was demonstrated as early as 1945 with his Polish art, a brief introduction to the subject, and more fully with his Art of the Medieval World (1975) which covered all arts from the 4th to the 15th century, remains a standard synthesis, and was recently translated into Chinese.

George Zarnecki's outstanding place as a scholar and teacher can be traced in his publications, and in the honours bestowed on him during his career. Yet to those who knew him, these achievements were matched by the warmth of his personality. Immediately striking was the old-world continental charm which remained with him to the end. But in his case the charm was matched by a deep-seated kindness, concern for others and a gift for friendship. Generations of students and colleagues from the Courtauld and further afield will attest to the importance to them of his kindness, his helpfulness, advice and support, often at key points in their lives.

Michael Kauffmann

Jerzy (George) Zarnecki, scholar of medieval art: born Stara Osota, Russia (now Ukraine) 12 September 1915; junior assistant, Institute of Art, Krakow University 1936-39; staff, Courtauld Institute of Art 1945-61, Deputy Director 1961-74, Honorary Fellow 1986; Reader of History of Art, University of London 1959-1963, Professor 1963-82 (Emeritus); CBE 1970; married 1945 Anne Leslie Frith (one son, one daughter); died London 8 September 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks