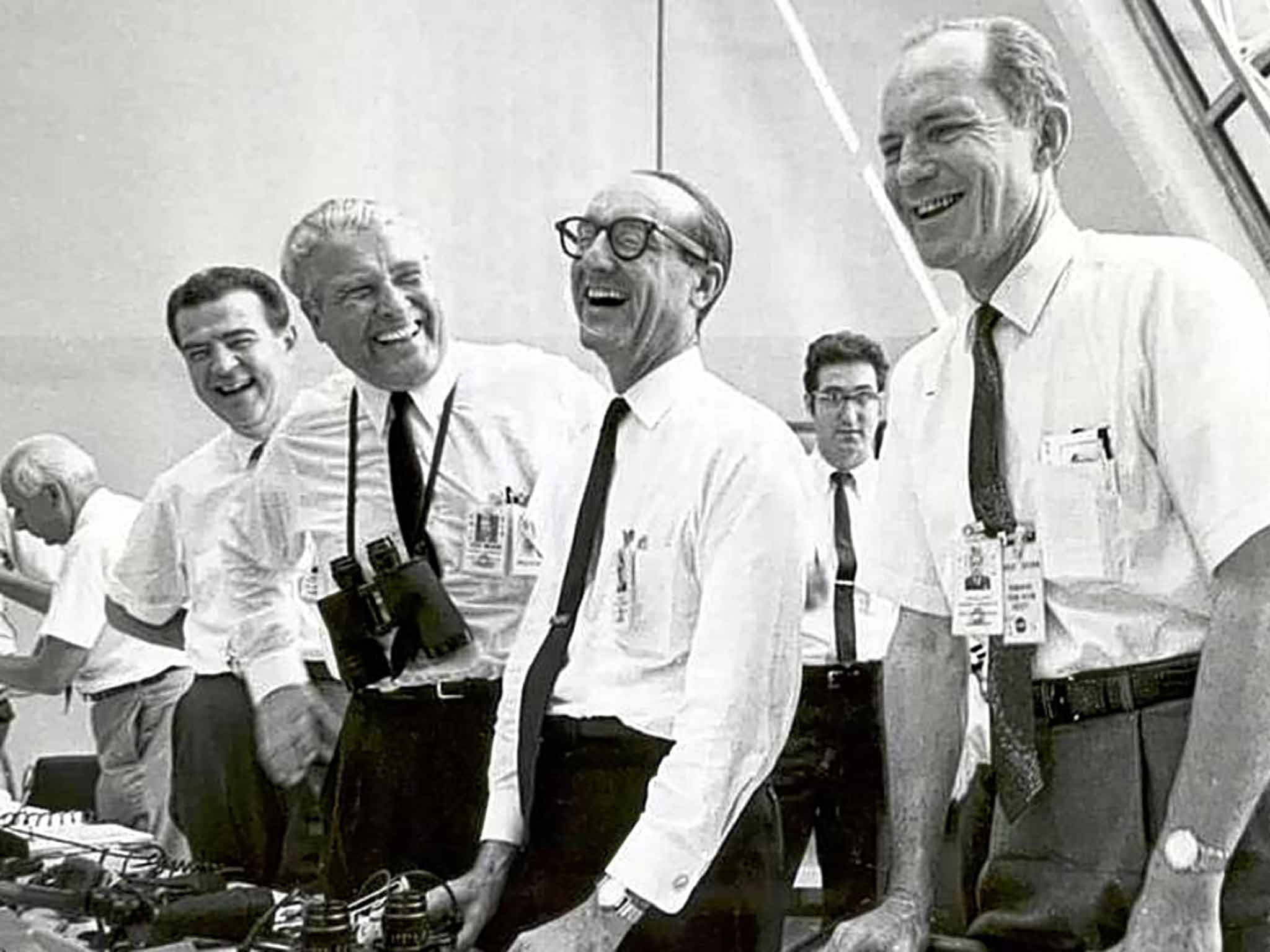

George Mueller: Nasa engineer whose decision-making played a significant part in the Apollo 11 moon landing

He helped design Skylab, America's first space station, and spoke out strongly in favour of a lower-cost, reusable launch vehicle

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.George Mueller, who has died aged 97, was a coolly decisive engineer, scientist and administrator who was given much of the credit for enabling Nasa to meet President John F. Kennedy's manned moon-landing timetable, as well as for initiating the Skylab and space shuttle programmes.

As head of Nasa's Office of Manned Spaceflight, with the title of associate administrator, Mueller bore much of the burden of seeing to it that the space agency's Apollo programme met the challenge Kennedy issued in a celebrated 1961 address: landing a man on the moon – and bringing him back – by the end of the 1960s.

During the Cold War, a manned moon landing became a major US goal and was considered a symbol of the country's will and determination, particularly in view of what was perceived as a space race with the Soviet Union.

In Mueller, Nasa was said to have installed a leader who understood both rocket science and human psychology. At key moments, according to space histories, he showed himself to be adept at assessing risk and to be bold in acting on his assessments.

One of his significant contributions was what came to be known as the “all-up” philosophy of rocket and spacecraft testing. As its name suggests, “all-up” was a form of examining everything to be used for a space mission all at once, as opposed to incremental modes of proceeding inch by slow inch.

As applied to the space programme, it implied specifically such techniques as the testing of all three stages of the giant Saturn V booster rocket while they were coupled together – and with a payload attached, to boot. It was reported that the scheme had its doubters, among them such leading lights of rocketry as Wernher von Braun.

But in time, Mueller proved persuasive enough to overcome all such reservations, and it was “all-up” for the mammoth Saturn V, the launch vehicle upon which Nasa pinned its hopes of sending Americans to the moon.

Ultimately, a Nasa history read, “it is clear that without all-up testing the first manned lunar landing could not have taken place as early as 1969,” the last year that met Kennedy's schedule. Frank Borman's Apollo 8 crew orbited the moon on Christmas 1968, and in the next year, the sixth Saturn V took Neil Armstrong's Apollo 11 to the first manned lunar landing.

Mueller maintained that he was not being rash in sending Apollo 8 to circle the moon after the rocket that was to lift it into space had flown only twice, neither time carrying men aloft. “It wouldn't have gone if I hadn't been comfortable,” he said. “I spent about four months that summer looking at every possible way that it could fail, and convinced myself that it wasn't going to fail,” he said.

In January 1967, Nasa suffered one of its most devastating setbacks to that point. Three astronauts were killed in a fire during a launch-pad test. The response given then by Nasa's administrator, James E Webb, helped show how well Mueller was regarded. Despite the tragedy, Mueller remained in his job, because, Webb said, he was “one of the ablest men in the world.”

George Edwin Mueller was born in St Louis, Missouri on 16 July 1918, a few months before the end of the First World War.

As a boy, he was captivated by science fiction, and he also built model planes powered by rubber bands. At what was then the Missouri School of Mines, a technical school, he studied electrical engineering and received a bachelor's degree in 1939. He received a master's degree, also in electrical engineering, from Purdue University in Indiana in 1940.

As a young graduate, he held jobs in which he worked on the development of microwave tubes, television and radar. He worked at Bell Labs in New Jersey and took graduate courses at Princeton University. As an assistant professor of electrical engineering at Ohio State University, he worked toward his doctorate, receiving a PhD in physics in 1951.

In the 1950s, he went to work in the aerospace industry. He joined Ramo-Wooldridge Corp. and remained there through a merger into what was to become TRW. He played an important role in the development of the intercontinental ballistic missile, and he began to formulate his “all-up” program of testing.

In the 1960s, work on rockets became increasingly associated with Nasa, and ultimately, Mueller was drawn in at a high level, starting as deputy associate administrator.

In addition to his management of the moon programme, he helped design Skylab, America's first space station, and spoke out strongly in favour of a lower-cost, reusable launch vehicle. The space shuttle embodied some of the concepts of reusability that he advocated.

After the moon landing, Mueller left Nasa in December 1969, but later returned to the space industry. He was an executive with General Dynamics and then held top posts at System Development.

Beyond the competitive aspects of the space race, Mueller believed in the importance of space exploration. “The only question,” he once said, was “whether this nation will prevail in space... or whether we will abandon the future to others.”

George Mueller, Nasa scientist: born St Louis, Missouri 16 July 1918; died Irvine, California 12 October 2015.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments