George Elsey: Adviser to Roosevelt and Truman in the Map Room, the epicentre of US operations in WWII

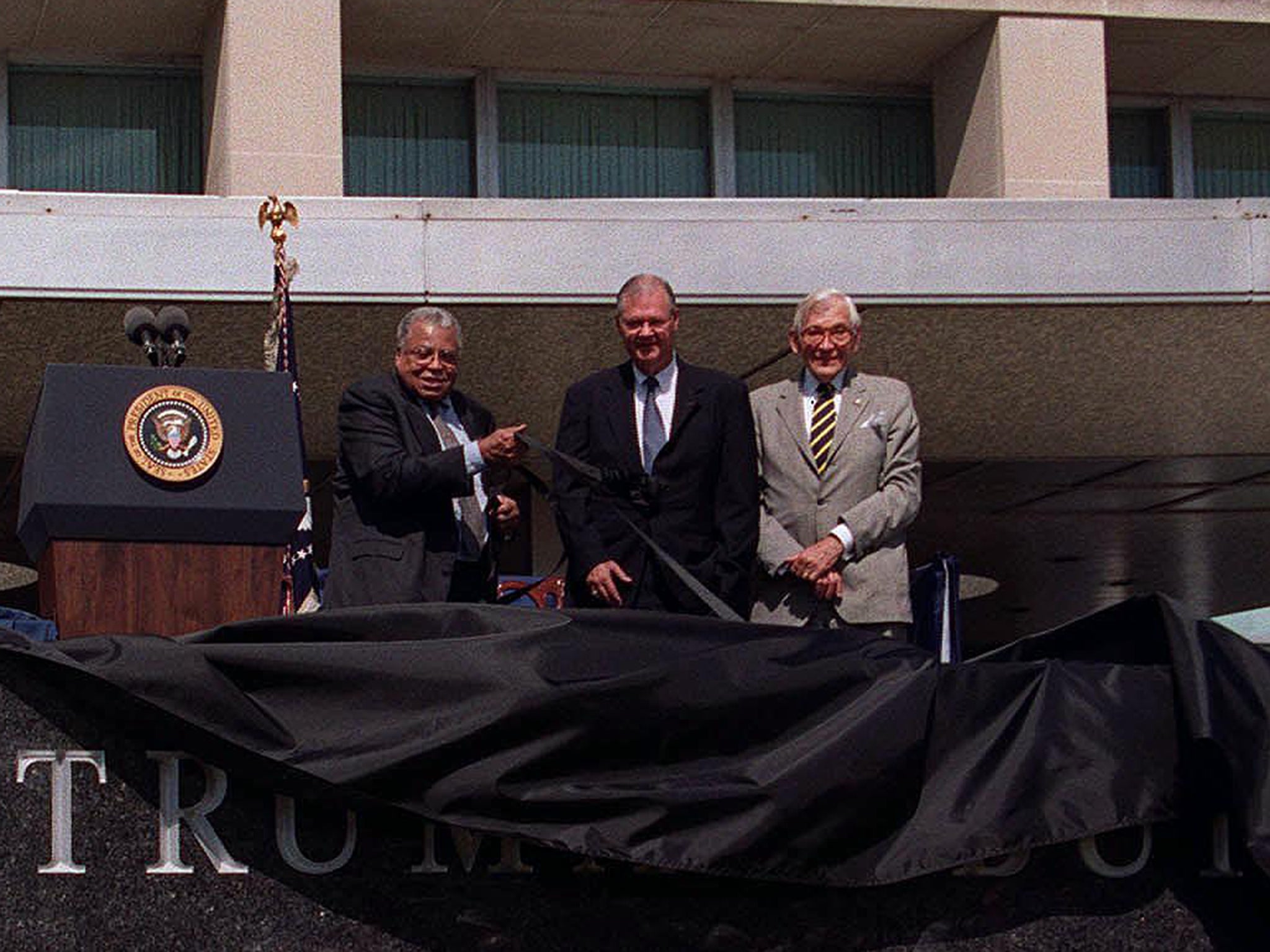

Elsey's proudest achievement was to have changed the presidential flag and seal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.George Elsey studied history, had a ringside seat at history, and then helped make history. Almost certainly he was the last surviving eye witness of the innermost workings of the White House during the Second World War – and perhaps the only person still alive who had been acquainted with Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman and Winston Churchill, and who had met Joseph Stalin.

Elsey had been a brilliant student at Princeton before taking a Masters in history at Harvard. He intended to take a doctorate, but in December 1941 the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour and the US entered the war. Cutting short his studies, he joined the Naval Reserve, hoping to work in naval intelligence. Instead, in April 1942, Elsey was assigned to the Map Room, the wartime nerve centre of FDR’s White House.

The Map Room, on the ground floor of the presidential residence, handled Roosevelt’s most sensitive communications with Churchill, Stalin, Chiang Kai-shek and other allied leaders. On its walls were displayed maps with the latest troop and naval positions around the globe. So restricted was it that the secret service not was allowed inside, nor even the vice-president.

Roosevelt had it staffed by young reserve officers like Elsey, then 24, so that active duty officers could go to war. In the Map Room they coded, decoded, read and transmitted messages that shaped the course of the Second World War. They were aware of key future plans, like D-Day, before they happened, and the existence of the Manhattan Project to develop the first atomic weapon.

Until he set eyes on Roosevelt, Elsey – like most Americans – had no idea the president was virtually confined to a wheelchair. In fact, FDR himself spent less time in the Map Room than did Churchill when he was at the White House. Elsey liked the Prime Minister for his approachability. Roosevelt, he said, was civil, but “up in the clouds, looking down.” Truman, however, “was impossible not to like… right down on the ground with us.”

Memorable moments were many, two especially from a May 1943 visit by Churchill. On one occasion he handed Churchill news that the allies had sunk three German U-Boats, which Churchill realised meant that the ultra-secret Enigma code had been broken. According to Elsey, the Prime Minister jumped up and down and shouted, “We got them! We got them! We got them!”

At about that time, an urgent demand came in from Stalin that the US and Britain open an immediate second front in northern Europe, to take pressure off the Soviets, who were fighting the Nazis in the East. After an evidently “convivial” dinner upstairs, Elsey recalled, Roosevelt and Churchill entered the Map Room and settled down to business. “What are we going to say to Uncle Joe?” they wondered, but couldn’t agree on an answer. “The British insisted they were not ready, but the Americans pressed for the earliest possible attack.” The outcome was a meaningless fudge, which Elsey typed out.

Eventually plans for the invasion of France were agreed at the Quebec summit four months later. But the memory of that night never left Elsey. “Here was I, a kid, listening to Roosevelt, Churchill and the Joint Chiefs of Staff arguing over the principal strategy of World War II, “ he told The Orange County Register in 2013.

After Roosevelt died in April 1945, Elsey continued in his job under Truman, who only after being sworn in was told about the Manhattan Project. He accompanied the new president to the Potsdam conference with Churchill (later Clement Attlee) and Stalin, personally passing the news to Truman that the first atomic test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, had been successful.

Elsey never had the slightest doubt about the Bomb. The assumption, he said later, was that if it worked, it would be used. Assumption became certainty when the Japanese rejected the surrender terms set out at Potsdam. In fact, he told a 2009 interviewer, “the Japanese were the ultimate benificiaries of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Far more people would have been killed in a systematic conventional campaign. The blame lay with the Japanese for rejecting the Potsdam declaration.”

Elsey’s relationship with Truman was much closer than with FDR. After 1945, he served not just as a communicator of policy, but as a shaper of policy, at home and abroad. He was co-author with Clark Clifford, another Truman aide, of a 1946 report that warned so bluntly of the emerging Soviet menace that the President ordered it kept top secret and every copy returned to the White House.

Elsey also helped set down on paper the Truman Doctrine, promising support for countries threatened by communism, before being drawn into the President’s campaign for the 1948 election, which practically everyone bar Truman believed he would lose. Elsey was on the legendary Whistle Stop train tour that cemented Truman’s recovery, writing sometimes as many as 15 speeches a day.

In 1951 he left the White House, returning to government in 1968 when Clifford, his friend from the Truman days, served as Defence Secretary for the final year of the Johnson administration. Elsey later became president of the American Red Cross and head of the White House Historical Association.

His proudest achievement, however, was to have changed the presidential flag and seal. The change was requested by Roosevelt who objected to the mere four stars it displayed (one fewer than the newly created rank of five-star general). Elsey increased the stars to 48 (the number of states at the time), and switched the head of the eagle’s head from looking left to looking right - in heraldic terms a shift from illegitimacy to honour. Each time he saw the seal thereafter, Elsey said, he thought, “I did that.”

George McKee Elsey, naval officer and US government official: born Palo Alto, California 5 February 1918; married 1951 Sally Phelps Bradley (two children); died Tustin, California 30 December 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments