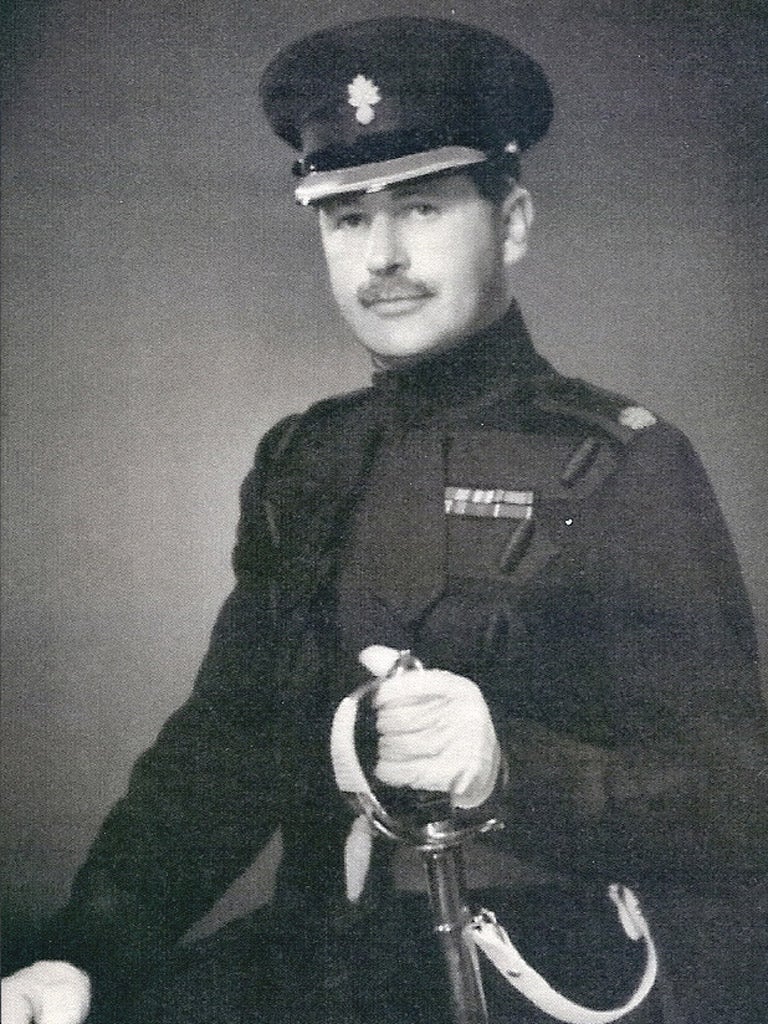

General Sir David Fraser: Soldier who was first with his men into Brussels after D-Day

Few can have expressed the romance of soldiering as vividly as David Fraser. His dash to Berlin with the Guards Armoured Division in the last year of the Second World War began with an eve-of-D-Day dinner in Brighton with his fellow officer, the artist Rex Whistler. In liberating Paris, he raised a glass at the Ritz, watched by Ernest Hemingway.

On 3 September 1944 he and his men were first into Brussels in front of the British Second Army. Ordered to the Royal Palace of Laeken, on the city's north-west edge, Fraser used childhood memories of the place to get there, and found the Queen Mother (Elisabeth) of the Belgians waiting in gratitude on the drive to shake every one of them by the hand.

The British XXX Corps, under Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, were invited to use the Palace – where the Nazis had imprisoned her family before deporting them – as headquarters. Fraser's men slept in the gardens, and pressed on next day.

So eager was Fraser, a future Vice-Chief of the General Staff, to join up at the outbreak of the Second World War that he had abandoned school and started his 40-year military career as a mere private, before the Grenadier Guards would let him in.

School was Eton, which he loved and regretted leaving, but the call of the bugle was sharpened by four generations of his family having served since his grandfather's great-uncle defended the orchard of Hougoumont at the Battle of Waterloo.

Obliged to cool his heels, he got in to Christ Church, Oxford, where he switched subjects from Politics, Philosophy and Economics to his lifelong love, History. Meanwhile, the phoney war turned real.

Before he pulled on the perfectly polished boots and splendid kit of a Guardsman, one more trial awaited him: the discovery of how wretched, disunited and ill-attuned his fellow Britons were to the exigencies of war. Bands of young thugs, many with criminal records, were encouraged to join the Young Soldiers Battalions of the Home Defence Force, and one of these was the 8th Battalion, the Royal Berkshire Regiment which Fraser joined as a private, soon being made a junior NCO with other educated young men and given charge of them. The lads derided Fraser's sort as "college boys", and shocked them with their ill-gotten knowledge of the world.

It became Fraser's abiding opinion that Britain was a bit of a rum place in 1940, and that the peacetime army of 1960, had it been called on, was in much better shape to have withstood the always-surprising shock of war.

He spent the middle years of hostilities mostly exercising Sherman tanks on Salisbury Plain with the newly formed and mechanised Guards Armoured Division, and conceived great admiration for the man who first commanded it, Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese.

His experience of Leese's character chimed with a tribute paid later by Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, after Leese's unhappy dismissal in the Far East in a dispute over who was to lead the Fourteenth Army in Burma. Leese had been "manly" in criticising no one, Alanbrooke recorded, and Fraser, who wrote Alanbrooke's biography, concluded from his words that Leese was, in Guardsmen's terms, "carted" by the Supreme Commander of South-East Asia, Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Fraser got to know the quirks of men and tanks, not only on Salisbury Plain but in the terrible battles through the Normandy "bocage" – rolling pastures and winding lanes bounded by tall hedgerows – beautiful as Devon but stinking with death and the smell of burning machines.

He considered the American Sherman less than ideal, with its low-velocity 75mm gun and propensity to burst into flames. When the Division later encountered German Tigers with their 88mm weapons, he said he felt like a man with a rapier fighting spearmen with thickly armoured breastplates.

He also learned that a man might love his tank as much as any warrior his horse or ship, when he found a soldier distressed that he had been picked to march in a victory parade instead of riding in the Sherman that had got him through the campaign.

Fraser commanded men in Malaya in 1948 and 1949 during the Emergency, attended Staff College, and was sent to Whitehall and the War Office. In 1951 he took the 3rd Battalion of Grenadiers to Port Said; in 1952 he became Brigade Major of the 1st Guards Brigade; and in 1954 Regimental Adjutant.

He was in Cyprus in 1958, then from 1960 until 1962 commanded the Grenadier Guards' 1st Battalion when they were deployed to Cameroon. He then served in Sarawak at the head of the 19th Infantry Brigade during the Indonesian Confrontation of 1965.

He returned to study at the Imperial Defence College, after which, as the Army's Director of Plans from 1966, reorganised as Director of Defence Policy until 1969, he jousted with the Labour Government's Defence Secretary, Denis Healey. This was a time of deep cuts in funding, but he believed that Healey invigorated defence thinking.

With delight he went back to command, at the head of the 4th Division on the Rhine. When he returned to Whitehall, he had as Defence Secretary his friend and former fellow officer in the Grenadiers, the Conservative Lord Carrington.

Fraser became Vice-Chief of the General Staff (1973-75), then British Military Representative to Nato in Brussels. He knew the city well, having lived there when his father had been military attaché. His last post from 1977, before retiring in 1980, was as Commandant of the Royal College of Defence Studies. His literary output included biographies of Alanbrooke, Rommel and Frederick the Great, and the fictional Hardrow Chronicles and Treason in Arms series.

While bringing up his family at Isington in Hampshire he was a neighbour of Field Marshal Montgomery of Alamein, now buried nearby at Holy Cross Church, Binsted. He came to know all of Monty's charms and flaws, and says in his fine memoirs, Wars and Shadows (2002), that this person, through his self-belief hugely able to impart confidence to others, was one that Britain in the dark landscape of 1940-41 had sorely needed.

Fraser was Colonel of the Royal Hampshire Regiment from 1981 to 1987, and a deputy Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire from 1988. For all the time he spent in England, David Fraser felt himself strongly a Scot. He was the nephew of Lord Saltoun, descendant of the elder brother of the progenitor of the Frasers of Lovat. The designation chief of the name of Fraser today belongs to Fraser's cousin, Flora Fraser, Lady Saltoun.

Anne Keleny

David William Fraser, soldier, historian and author: born London 30 December 1920; OBE 1962, KCB 1973, GCB 1980, Hon D Litt Reading 1992; married 1947 Anne Balfour (divorced 1952, one daughter), 1957 Julia de la Hey (two sons, two daughters); died Isington, Hampshire 15 July 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks