Frith Banbury: Veteran theatre director who was a champion of dramatists such as Robert Bolt and Rodney Ackland

'The play produced by Frith Banbury" – that old style of director's credit appeared in the programmes of some of the most distinguished theatrical successes of the 1950s. The name itself, along with that of the impresario Hugh ("Binkie") Beaumont, seems to evoke the West End at its most French-windowed, all that the "revolution" at the Royal Court supposedly swept away. Indeed, Banbury did direct many of that era's sleekest productions, in partnership with the H.M. Tennent management headed by Beaumont, including Waters of the Moon (Haymarket, 1951), Tennent's Festival of Britain production, starring Edith Evans, Sybil Thorndike and Wendy Hiller.

Virtually all Banbury's unusually long career was spent in the unsubsidised theatre, and from the 1960s onwards he was regarded as the director to hire for starry, safe revivals or literary adaptations of period novels. Yet he had made his name as a director with new plays, and championed dramatists such as Robert Bolt and, crucially, Rodney Ackland, whom he supported, morally and financially (Banbury had a private income), for many years. Recent interest in this virtually "lost" writer is in no small measure due to him.

Another paradox about Banbury is that the director most associated with the "theatre of reassurance" was a homosexual, Jewish pacifist. His sexuality he handled discreetly, always remaining aloof from what was known as "the Homintern" surrounding the Tennent regime. (Beaumont referred to Banbury, in the camp-speak of the time, as "the Admiral's gifted daughter".)

Banbury's background was indeed conventional – his father was a distinguished Rear-Admiral, and Frith was educated, after a miserable prep school, at Stowe, where he began the rebellion against all that his father stood for. His mother, descended from a Russian Jewish family, took him to his first play and soon afterwards gave him a model theatre: "From then on the theatre's been a religion to me. Some get Christianity. I've got theatre," he later said.

He went to Oxford to read Modern Languages but left after a year to go to Rada, in 1931, where he met Rachel Kempson and Joan Littlewood, who became lifelong friends. His acting career – 1933 to 1947 – was busy. An habitué of that vanished, somewhat louche world of inter-war West End clubland, he found a niche in the related atmospheres of first the Players', a private theatre then in Covent Garden, and then in intimate revue. He scored a big success in Let's Face It (Chanticleer, 1939), then moved into New Faces (Comedy, 1940).

His more legitimate career also continued steadily. Close friends with Robert Morley and Peter Bull, he had happy times at their summer venture at Perranporth, transferring to the West End with Morley's comedy Goodness, How Sad! (Vaudeville, 1938). Never a conventional leading man, he tended to be cast in more farouche roles, such as Khlestakov in The Government Inspector (Glasgow, 1945).

The switch to directing was abrupt. Michael Gough, an actor friend, gave him the manuscript of Wynyard Browne's Dark Summer, a promising first play set in an English provincial city just after the war, centred on a blinded soldier. Banbury bought an option on the play and, after a short tour, it opened in the West End in 1947. It had only a modest run, but Banbury knew where his future now lay. Backed by a loan from his mother, he optioned Browne's next plays, and The Holly and the Ivy, a subtle study of family tensions in a Norfolk vicarage over Christmas, was a considerable success (Duchess, 1950). Banbury's ability to handle actors was evident, and soon he was in considerable demand.

Rodney Ackland – like Browne a complex, bisexual personality – first worked with Banbury on a revival of his version of Hugh Walpole's The Old Ladies, on which they had a happy association. Banbury became a champion of Ackland's original plays, particularly The Pink Room (Lyric Hammersmith, 1952), set in a West End drinking club against the background of the 1945 election, with a large cast of lost souls presided over by the owner Christine (superbly played by Hermione Baddeley). Despite a strong cast – including a young Canadian, Christopher Taylor, who became Banbury's trusted associate – the play received uncomprehendingly hostile reviews, devastating the hypersensitive Ackland whose career never properly recovered.

As well as N.C. Hunter's Waters of the Moon, a piece of ersatz Chekhov which Banbury directed as if it were the real thing (it ran for two years), Banbury was also vital to the success of Terence Rattigan's The Deep Blue Sea (Duchess, 1952), coaxing some valuable rewrites and working closely with Peggy Ashcroft as Hester to shape a revelatory performance of sexual hunger.

He was instrumental in bringing Robert Bolt to prominence, directing his first London play, Flowering Cherry (Haymarket, 1957), with Ralph Richardson as the insurance salesman dreaming of escape and Celia Johnson as his wife. A second Bolt production – The Tiger and the Horse (Queen's, 1960) with Michael and Vanessa Redgrave – was less happy, if commercially successful. It was poorly designed and uneasy in tone; Banbury claimed later that the recently knighted Redgrave "fucked it up" by avoiding the less admirable aspects of the aloof academic Jack Dean to gain the audience's sympathy. He also directed John Whiting's Marching Song (St Martin's, 1954) which he much admired, but it was a prestigious flop.

Banbury worked with Tom Stoppard – "hot" after the success of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead – when he took on a reworked version of an early television play, Enter a Free Man (St Martins, 1968), but it, too, was a flop. And his one excursion into the classics – an over-careful Love's Labour's Lost for an under-strength Old Vic (1954) – was also unsuccessful.

He had more success with adaptations – such as Christopher Taylor's sensitive version of Henry James's Wings of the Dove (Lyric, 1963), with Susannah York as the dying Millie. But revivals such as a patchy Ingrid Bergman vehicle Captain Brassbound's Conversion (Cambridge, 1971) and a valiant effort on the moth-eaten Reunion in Vienna (Chichester, 1971) with Margaret Leighton, called for little more than his staging expertise and tactful handling of stars.

With top-flight material however, his talents could illuminate a theatre. He did a magnificent job on The Aspern Papers (Haymarket, 1984), a scrupulous re-examination of the fine Redgrave version of James's story, suffused with suspense and with remarkably disciplined performances from Wendy Hiller, Vanessa Redgrave and Christopher Reeve. Every aspect of this venture was informed by the taste and unshowy mastery of staging that were the hallmarks of Banbury's style.

He remained astonishingly young – mainly by keeping in touch (he was an avid theatregoer into extreme old age) – and was directing well into his eighties. In 1989 he presented and directed an offbeat new play, Screamers (Arts) and, in the West End, in 1999 revived the US comedy The Gin Game (Savoy) with Joss Ackland and Dorothy Tutin.

In 2003 – aged 91 – he directed one of his past successes again when The Old Ladies was revived on a national tour. It was cast with three of Banbury's favourite modern actresses – Rosemary Leach, Siâ*Phillips and Angela Thorne – and atmospherically set, but he must have seen how theatrical tastes had changed when a piece that had once chilled with clammy suspense seemed tamer fare in an altered world.

Alan Strachan

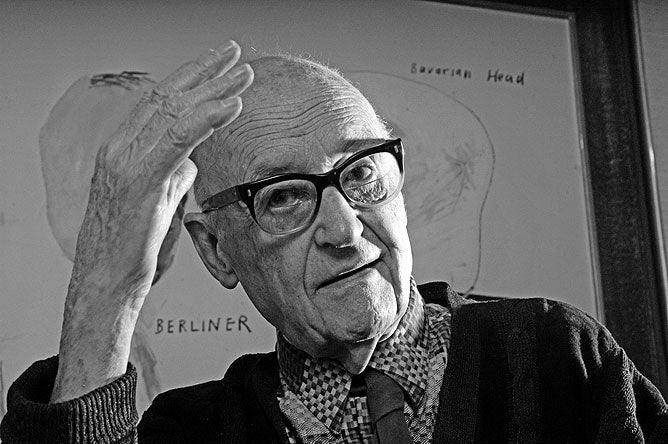

Frith was a mere stripling of 80 when I first met him at a party, writes Simon Callow. I knew of him as the legendary director of some of the West End's greatest hits of the 1940s and 1950s and expected venerability. This was immediately belied by his appearance, sharp and elegant, and somehow rather modern – a very jazzy tie, snazzy shoes, a strikingly cut jacket.

He was attacking the buffet table with some address, but paused for the introduction. "Oh, yes, I know who YOU are, certainly," he said, and cracked straight into a commentary on my career which rapidly encompassed the rest of the present theatre scene. He was exceptionally well-informed, precise and sometimes withering in his judgements, and full of laughter. Any attempt on my part to direct the conversation to the past, and particularly his past, was fiercely resisted. "So boring, all that." We met now and then, started to have meals together, and somewhat later began going to the theatre, which until very recently he liked to attend three or more times a week. Despite difficulties with his legs, he positively surged towards the auditorium.

His tastes in theatre were all-embracing. One of the first shows he suggested that we see together was Jerry Springer: the Opera. He rejoiced in its profanities, so much so that I had to ask the National Theatre's literary department for a copy of the lyrics, so that he could scrutinise them more carefully for any obscenities he might have missed. This impeccable supposed elder statesman of the theatrical establishment adored nothing more than to cock a snook at it. "Why are you surprised?" he said. "I'm a homosexual, half-Jewish conchie. Just because my father was an admiral doesn't make me one of them."

Alarmingly, he started to come to see shows that I was in, sitting in the middle of the front row because of his declining hearing, his face upturned with eager concentration, his spectacles glinting. When he came backstage he was always kind but unsparing, often making brilliant suggestions for the show's improvement; after all, he had spent his life as director fixing plays, working tirelessly with writers on structure, text, character, motivation. Our conversations were not only entertaining, they were highly educational.

It was, none the less, a considerable surprise when he telephoned early last year to say that he had decided that he wanted someone to write his biography, and that I was the obvious choice. He had, he said, things to say. The book was only of interest, he added, because he was nearly 95 and had lived through so very much. It wouldn't have to come out till he was dead, so there was no rush. I stammered my acceptance, having no time at all for such a task, but thinking that it wasn't terribly pressing. The next day he called back to say that he'd been thinking: perhaps he would rather like to be around when it came out, so we'd better get going.

And so we did. At every available moment, I went round to his Regent's Park flat, the walls filled with the Hockneys which he had so cleverly bought for a tenner apiece, and he talked with dazzling lucidity and extreme candour about his life and times. His memory was superhuman: he would reel off the names of all the understudies on a production in which he'd acted in 1934, with detailed accounts of their subsequent careers or lack thereof, and sharp analyses of why. We worked rigorously through production after production. It became evident that, far from a mere safe pair of hands, he had been something of an innovator, among other things the director of two black plays, Moon on a Rainbow Shawl and Mr Johnson in the late 1950s at a time when The Black and White Minstrel Show was still packing 'em in in the West End.

Our sessions became very important to him. When he fell ill a couple of weeks ago, he gave me priority over any other visitors. Our session last week was a struggle; his memory seemed finally to have pegged out. But then on Monday of this week, I was there again, and though physically he had become gaunt and yellow, resembling his beloved Delius at the end of his life, his mind was sharp again. What was it like, I asked, to work with Cicely Courtneidge. "There was WARMTH," he said, "that's all that matters – warmth." He said it, for some reason, in a broad American accent – "waaaaarmth". He fell asleep almost immediately, and I left soon after. As a director, Frith had been a fierce task-master; as a man it was his waaaaaarmth that one loved.

Frederick Harold Banbury (Frith Banbury), theatrical director, producer and actor: born Plymouth, Devon 4 May 1912; MBE 2000; died London 14 May 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks