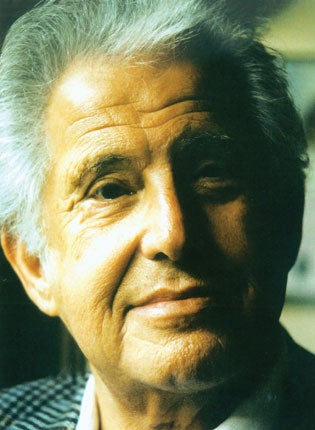

Freddy Bienstock: Music publisher whose portfolio encompassed acts as diverse as Cliff Richard and James Brown

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the bigger lions in the international music industry jungle, Freddy Bienstock, who has died aged 86, was the mainstay of Carlin Songs, whose roster of pop talent facilitated its growth as a major publishing concern, occupying several addresses in New York alone, and emerging as the second largest UK company in its field. A portfolio of over 100,000 compositions spanned a century of copyrights, covering all stylistic waterfronts.

Bienstock was not, however, born into showbusiness, and it was not considered a feasible vocation by his Jewish family, who moved from Zurich to Vienna when he was three. Soon after Hitler’s seizure of Austria in 1938, he and his brother Johnny were sent to stay with an uncle in New Jersey, their parents joining them two years later, and settling in New York.

While he began his working life driving a van for a wholesale grocer, he came to know the complex mumbojumbo of music publishing lore on landing a post in 1943 as a junior stock controller at Chappell and Co., a leading conglomerate in Tin Pan Alley, then the storm centre of the Big Apple’s music trade. It was to be a moment of supreme satisfaction when, in 1984, he became Chappell’s chairman and majority stockholder.

Promoted to song-plugger, he placed Chappell product with Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey and such bandleaders omnipresent in city centre clubland in the 1940s, and visited regional radio stations to ensure that the consequent discs were on playlists.

Yet, if pop was a commodity to be bought, sold and replaced when worn out, Bienstock was not deprecating about his knowledge and love of it – a virtue that impressed his cousins Julian and Jean Aberbach, proprietors of Hill and Range, who specialised in country and western.

Overseeing St. Louis Music, the partnership’s subsidiary division, he entered the orbit of Colonel Tom Parker, manager of Eddy Arnold and Hank Snow before devoting all his energies to Elvis Presley, whose early releases had not immediately excited Bienstock.

“I was not enamoured with rock ’n’ roll,” he confessed, “but I changed after a while. By listening to the songs that were submitted to me for Elvis, I soon had a good idea what he wanted.

I’d take the demos to Memphis, and have him select from them.” Among jobbing teams whose works he put before the King and other artists were Burt Bacharach and Hal David, Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, Sid Tepper and Roy C. Bennett and, especially, Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller. Like Bienstock, they commuted to Times Square’s Brill Building, the songwriting “factory” where assembly-line pop was churned out for the masses.

As perhaps Presley’s closest adviser on repertoire, he would claim with quiet pride that “for the first 12 years of his career, Elvis wouldn’t look at a song unless I’d seen it already.” Independently of him, however, Presley discovered a 50-year-old Italian ballad, “O Sole Mio” – though he asked Bienstock to commission the writing of English lyrics to the melody. As “It’s Now Or Never”, it was a 1960 No 1.

By then, Bienstock was regarded as one of the industry’s most powerful moguls, a standing that had been enhanced by what some perceived to be a dynastic marriage to Miriam, daughter of Herb Abramson, cofounder of Atlantic Records. She was in the business herself, as would be her and Freddy’s children, Robert – and his older sister Caroline, after whom, in a fashion, Carlin was named when Bienstock bought and retitled London- based Belinda Music, another Hill and Range affiliate, in 1966.

For several years, he had been serving Britain’s Cliff Richard in much the same way as he had Presley, chiefly by providing domestic No 1s in “Travellin’ Light” and 1962’s “The Young Ones”, both from Tepper and Bennett. Nevertheless, when the Sixties started swinging, Bienstock’s administrative caress came to encompass Billy J.

Kramer, The Animals, The Kinks (whose “I Go To Sleep”, written by Ray Davies was, through Carlin, recorded by Peggy Lee) and further British Invasion chart contenders. Later, Carlin – winners of 10 consecutive annual Top Publisher awards in the UK trade periodical, Music Week – ministered likewise to the Move, Pentangle and Genesis.

Bienstock’s good fortune enabled him to leave Hill and Range to focus more exclusively on Carlin, and also to establish the Hudson Bay Music Company with Lieber and Stoller – a liaison that lasted until 1980 – and gain rights to the output of Bobby Darin, John Sebastian and Tim Hardin. His holdings were to extend to companies with James Brown, Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton and more outré singing composers such as the Los Angeles street busker Wild Man Fischer on their books, and controlling interests in Fiddler On The Roof, Cabaret, Godspell and later musicals that ran and ran on Broadway and in the West End, some of them being turned into movies.

In the 1970s, the Carlin empire expanded to Walt Disney soundtracks, and soul music wafting from Tamla Motown and, in trend-setting Philadelphia, Avco. The acquisition of the catalogues of nearly 200 North American writers – which contained “Ain’t Misbehavin’”, “As Time Goes By”, “Sweet Georgia Brown”, “Winter Wonderland”

and other standards – was, however, subject to seven years of litigation over rights issues, culminating in victory for Bienstock when the case reached the House of Lords.

With the turn of the decade, Bienstock allied with the estates of Oscar Hammerstein II and Richard Rodgers to annex items by George M. Cohen, Cole Porter and Jim Steinman – who, with Carlin, was to amass wealth through selections on Meatloaf’s million- selling Bat Out Of Hell 2 album.

Further market triumphs for Carlin during this period included collections by U2, Duran Duran and Michael Jackson (most conspicuously, Thriller), and Whitney Houston’s version of Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You”.

As well as an ear for even latter-day hits such as these, much of Bienstock’s success was because he was no grey eminence who preferred to distance himself from his clients. Indeed, up to his final illness, he cut an avuncular and approachable figure at Rock’n’ Roll Hall of Fame galas or conferences within Carlin’s offices in a Manhattan skyscraper or its tastefully decorated London headquarters up a spiral staircase in Chalk Farm.

Alan Clayson

Frederick Bienstock, music publisher: born Zurich 24 April 1923; married Miriam Abramson (two children); died New York 21 September 2009

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments