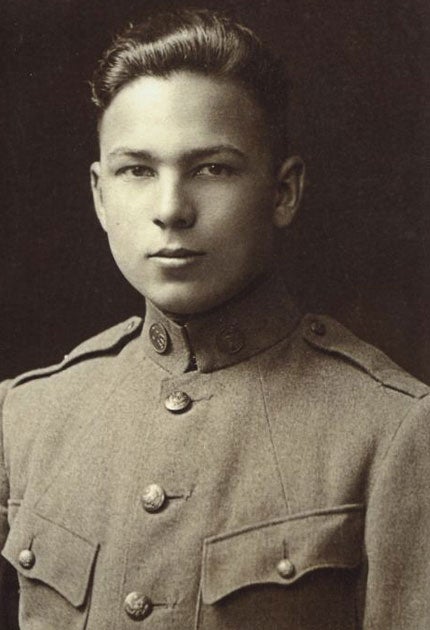

Frank Buckles: The last American survivor of the First World War

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.No one knows quite why American soldiers were once known as "doughboys". But Frank Buckles was indisputably the very last of them – the sole American still alive who went to Europe to fight in the First World War, after the US entered the conflict in 1917.

Like so many others, the 16-year-old farm boy from the Midwest was inspired to join up by a recruiting poster, but his first attempts were unsuccessful. When he told the Marines he was 18 but had forgotten his birth certificate, they laughed and suggested he go home before his mother noticed he was missing. The Navy rejected him, too, saying he had flat feet. So Buckles went for broke with the Army, saying he was not merely 18, but all of 21. It worked.

After preliminary training at Fort Riley in Kansas, he left for England in December 1917, aboard the RMS Carpathia, the ship that five years before had rescued survivors from the Titanic, and secured assignment to France as an ambulance driver. Buckles did not see action – indeed, he was never within 30 miles of the frontline – but as he liked to say later, "I saw the results." He had especially vivid memories of the French soldiers as they prepared to return to battle, spending their last night of leave in a village cafe.

"They had very little money," he told an interviewer from the Library ofCongress, "but they were drinking wine and singing the Marseillaise withenthusiasm. And I enquired, 'What is the occasion?' They were going back to the front, they told me. Can you imagine that?"

When the armistice that did end the "War to End All Wars" was signed in November 1918, Buckles helped repatriate German prisoners, many of them scarcely older than himself. He returned to the US with the rank of corporal, and in 1920 was discharged.

His initial plan was to go into business. Buckles took typing and shorthand lessons, and briefly worked in a bank. But he quickly became bored, and went to work for shipping companies and travelled the world. On a port call in Germany in the 1930s, he would claim, he saw Hitler in a hotel lobby.

The Second World War, however, was less kind to him. In December 1941, Buckles was in Manila when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour and then landed in the Philippines. He was taken prisoner and spent the next three years in filthy internment camps, including the infamous Los Banos. He was finally liberated in February 1945, ravaged by disease and weighing barely seven stone, by his own admission "astonished that any of us survived."

This time Buckles did settle down. He returned to the US, married, and in the mid-1950s bought a small cattle farm in West Virginia. There he would spend the rest of his life, driving his car and tractor until he was well over 100.

As the decades passed and the doughboys' ranks gradually thinned to near- vanishing point, Buckles became a listed national monument, a living link to America's great wars of the first half of the 20th century. He gave countless interviews, and was fêted at the White House, the Pentagon and Capitol Hill. Almost to the end he fought for his special cause, the creation of a dedicated federal memorial in Washington DC fit to honour the 4.7m Americans who signed up for the First World War and the 2m who went to Europe.

In 2008, the George W Bush administration bent the rules of protocol to permit Buckles – a mere corporal who had served barely a year in a combat theatre and had never actually fought – to be buried with full military honours in Arlington Cemetery, in a grave with a traditional white marble headstone, alongside some of the country's greatest heroes. "I knew there'd be only one some day," Buckles said as his life drew towards its end. "I didn't think it would be me."

Frank Woodruff Buckles, soldier and farmer: born Bethany, Missouri 1 February 1901; served US Army 1917-1920; married 1946 Audrey Mayo (deceased; one daughter); died Charles Town, West Virginia 27 February 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments