Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."I have often said that I am never happier than when I am writing," runs the final paragraph of Francis King's autobiography, Yesterday Came Suddenly (1993). "But it might have been better for me and for those close to me if it had not been so." Here King, ever sensitive to what he perceived as his own shortcomings, was doing himself an injustice. A prolific and accomplished novelist, whose output in his 1970s and '80s heyday ran to a book a year, he was also a gregarious man, devoted to his friends and prepared to travel enormous distances – sometimes literally – on their behalf. In a career that extended into its seventh decade, he wrote at least half a dozen novels that deserve a place in the late 20th-century canon.

King was born in 1923 in Adelboden, Switzerland, where his tubercular father, a senior officer in the Indian Police, had gone for treatment at a sanatorium. In later life, he would remember the taste of salt – a symptom of the disease – on his father's forehead as he bent to kiss him goodnight. His early years were spent in India – an "earthly paradise" according to his memoirs, but with a distinct undercurrent of violence: at one point King's father was near-fatally poisoned by his cook; an uncle was later murdered by a vengeful sepoy. Act of Darkness (1983), one of his best novels, draws on these early memories. Sent back to prep school in England, he became a remittance child, farmed out (together with his three sisters) on a succession of relatives. His status as a piece of human supercargo was confirmed by his Aunt Hetty's computation of taxi fares: "four shillings for us and sixpence for Francis." A realist in family matters, King claimed not to resent this.

The news of his father's death was brought to him during his first term at Shrewsbury. By his own admission, this affected him less than his mother's return to England to make a home for her children. A "priggish, prudish, conceited boy", he was ferociously bright, won a Classics scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford – he later changed to English Literature – and published his first novel, To the Dark Tower (1946), while still an undergraduate. Much of the writing was done at a farm in Essex where, as a conscientious objector, he had gone to work on the land. Here the unwelcome attentions of the local female talent prompted much soul-searching about his sexuality. Finally, on holiday in Venice two years after the war's end, he allowed himself to be seduced by a gondolier.

Although the firm of Home & Van Thal, who had brought out three of his novels, went bankrupt before it could publish his study of the Brownings – the excuse for his Italian trip – King's star continued to rise. He struck up a friendship with JR Ackerley, who invited him to review books for The Listener, while the observational powers that distinguished his fiction were noted by Dylan Thomas. "He has eyes and ears in his bloody arse," Thomas suggested, after an evening spent in King's company.

Taken on to the staff of the British Council, he spent the next two decades combining the writing of a stream of well-received novels with the life of a cultural haute fonctionnaire, lecturing at local universities and institutes and acting as factotum to a succession of visiting British dignitaries. These postings took him to Italy, Greece, Finland, Egypt (where, arriving during the Suez crisis, he was briefly placed under house arrest) and Japan. Though prepared to make the best of any destination wished upon him by the authorities in London, King felt a special affinity for Japan, believing that he had achieved an understanding of the national psyche denied to most western visitors. Certainly, the experience produced three of his best books: The Custom House (1961), The Waves Behind the Boat (1965) and a collection of short stories, The Japanese Umbrella (1964).

Like the rest of his compendious oeuvre, King's early work was marked by an extreme sensitivity to minor personal inconvenience. As one critic put it, the character in his fiction who enters an unfamiliar lavatory is almost certain to find something nasty lurking in the toilet bowl. It also fairly seethes with nervous tension. As the early stories collected in a much later selected volume, One is a Wanderer (1985), demonstrate, King specialises in people thrown into each other's company by family ties or long association who do not much like each other and strain for the opportunity to assert their own independence. Highlights from this early period include The Man on the Rock, a bitter study of accidie, and The Widow (both 1957), a shrewd and affectionate portrait – the model was his mother – of a middle-aged woman coming to terms with the privations of post-war England.

Hindsight renders the homosexual themes of his early books more deliberate than they may have seemed at the time. King later acknowledged that in the pre-Wolfenden days he described gay relationships in a carefully occluded code, decipherable by anyone who knew of his sexual orientation.

In 1966 he resigned from the British Council and returned to England to devote himself to his writing. To supplement his income – never large – he took freelance jobs, working as literary adviser to Weidenfeld & Nicolson and contributing book reviews to The Sunday Telegraph; he later graduated to the post of theatre critic. He was a generous if occasionally feline reviewer, remarking once of a work by Kingsley Amis: "Not many people could write a better comic novel than Jake's Thing, but Mr Amis is one of them."

He also, aided by his friend and benefactor, the novelist CHB Kitchin, bought a house in Brighton and set up as a landlord, renting rooms to language students and visitors to the local university. This provided the background to his novel A Domestic Animal (1968), which contains a thinly-disguised account of his affair with an Italian economist, Giorgio Balloni.

Unfortunately, the book – one of his best – involved him in a bruising libel case. One of King's acquaintances in Brighton was the former Labour MP Tom Skeffington-Lodge. A vainglorious man, convinced that his brief time in the House should be marked by a peerage, Skeffington-Lodge had written to senior figures in the Labour Party urging them to intervene on his behalf. The one-line reply he received from Lord Attlee, expressing the hope that he would "get what he deserved", Skeffington-Lodge took at face value and read aloud at a dinner party at which King was present. All this King put verbatim into A Domestic Animal, taking the precaution of disguising his original as a female character named "Dame Winifred Harcourt". By chance Skeffington-Lodge, thought never to have read a book in his life, picked up a proof copy at the house of a mutual friend, was outraged and threatened legal action. Withdrawn, rewritten and eventually re-issued, the novel was, King believed, denied the reception it merited. Ten years later he used the situation in which he had found himself as the basis for a second novel, The Action, which narrowly missed the 1978 Booker shortlist.

In later life King lived in Kensington, surrounding himself with friends, most though by no means all of whom were drawn from the literary world he inhabited. He had a taste for what he called "difficult women", and enjoyed the confidence of Ivy Compton-Burnett (of whom he left a memorable portrait), Olivia Manning, Sonia Orwell and Jean Rhys. Efficient, courteous and anxious to do his best by his friends, he was in demand as a literary executor, performing this service for Ackerley and Kitchin, among others, and occasional ghostwriter. Both LP Hartley's novel Poor Clare (1968) and the second volume of the journalist Godfrey Winn's memoirs benefited from King's attentions. "It is not often that, in his fifties, a writer can drastically improve his style" one reviewer noted of the Winn opus, somewhat to the nominal author's annoyance. This solicitousness extended to the literary community as a whole. In the 1970s, together with his friends Brigid Brophy and Maureen Duffy, he was a founder member of the Writers Action Group which agitated for Public Lending Rights. Later he was a notable chairman of International PEN.

In certain respects, King's later years were not easy. His novels, as he often pointed out, were well reviewed but sold modestly. The relative commercial success of Act of Darkness was a welcome boost, but by the late 1980s this impetus had diminished, and there were several changes of publisher. His personal life, too, was in disarray. David Atkin, his long-term companion, died of Aids in 1988, and in the same year King survived an operation for cancer. Meanwhile, his mother, to whom he was devoted, had reached her late nineties: she was to die at the age of 102. Typically, these concerns had no obvious effect on his output. He was as industrious in his seventies as in his twenties, producing a series of novels that, if anything, got better as he got older. The Nick of Time, which covers the plight of an asylum-seeker, made the 2003 Man Booker longlist.

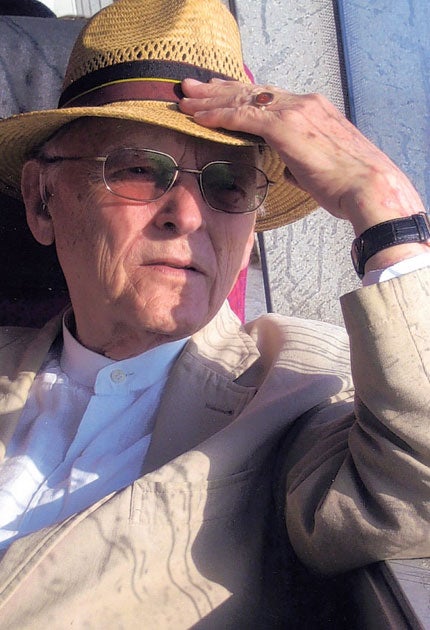

Nattily dressed and greatly at his ease, King continued to charm festival audiences into his mid-eighties, often with his friend Beryl Bainbridge. There was a memorable performance at the 2008 King's Lynn Fiction Festival, at which he discussed his sex life before an audience of admiring north Norfolk bourgeoisie. By the time of his death the literary category in which he reposed was all but extinct – the old-fashioned Man of Letters who relies on his pen and whose position grows ever more precarious with each new lurch in book-trade economics. But few 20th-century British writers have filled this vanishing niche with such indefatigability or distinction.

Francis Henry King, writer: born Adelboden, Switzerland 4 March 1923; OBE 1979, CBE 1985; died 3 July 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments