Franceso Cossiga: Pragmatic and controversial politician who served as prime minister and president of Italy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is no coincidence that Francesco Cossiga was both "a sincere Anglophile," in the words of one British ambassador, and a man obsessed with espionage. As minister of the interior during the late 1970s, when the threat of ultra-left terrorism to the Italian state culminated in the kidnapping and murder of ex-prime minister Aldo Moro, it was a necessary fixation, but for Cossiga it was also a love affair. "Some people like flowers," he once said. "I like spies."

Cossiga, who died on Tuesday aged 82 after suffering for years from cancer and depression, was one of the most precociously brilliant politicians of post-war Italy. A Sardinian from the city of Sassari, he was a devout Catholic all his life and joined the Christian Democratic Party in 1945, aged 17. He entered parliament 13 years later, becoming the youngest under-secretary of defence in 1966.

As the youngest-ever minister of the interior in 1976 at a time when terror attacks by the Red Brigades and other groups had escalated, he was the right man in the state's toughest job: in a secret note made public 30 years later, the former UK ambassador to Rome, Sir Alan Campbell, described him as "a sincere Anglophile with a practical approach that is unusual for a Christian Democrat, and with the reputation of being a minister who gets things done." A firm believer in Nato and in Italy's obligation to hold the line against Communism, he did not hesitate to send troops in armoured cars to crack down on demonstrations in Bologna.

When demonstrators were killed in Bologna and Rome his name was splashed across the walls of Italian cities spelled "Kossiga", with the two s's written as in the Nazi SS. Tough, dry and acerbic, "a Sardinian fist in a Christian Democrat glove" as one admirer put it yesterday – Cossiga could not have cared less, but when his close colleague Aldo Moro was kidnapped by the Brigades he was put to a more severe test.

From his abductors' hideout the former prime minister wrote to Cossiga, pleading with him to negotiate his release. Cossiga flatly refused to do so, but proved incapable of doing anything more pro-active. As interior minister he had re-organised the secret services, setting up special sections of police and Carabinieri to tackle the challenge posed by the radicals, but the Red Brigades who had seized Moro ran rings round them. Moro was finally executed by his captors after 54 days of torment.

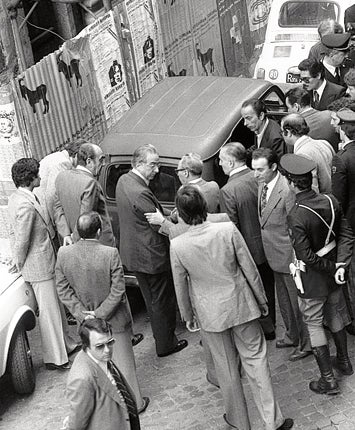

Devastated by his death, Cossiga rushed to the spot where the body was found, bundled inside the boot of a car midway between the offices of the Christian Democrat and Communist parties in central Rome. The following day he became the first post-war cabinet minister to resign.

For a more fragile character that would have been the end of a glittering though brief career. But although tormented by depression for much of his life, Cossiga recovered fast and the next year was appointed prime minister. Like most governments of the Christian Democrat era, his tenure was brief, lasting only a year and a half, and tainted by scandal: he was accused of leaking to a ministerial colleague the fact that the minister's son had been accused of being a terrorist killer, and of arranging for his escape. But the charge against Cossiga was dropped before he could stand trial.

Although a solitary figure with only a handful of close friends, Cossiga had the knack for making alliances across the political and cultural spectrum: on his death he received equally warm tributes from Pope Benedict XVI (who said he was "profoundly saddened" by the death of "an authoritative man of the faith") and by the Italian gay liberation organisation Arcigay, which saluted him "with affection... he was the first prime minister to receive a delegation from us. He was a truly secular premier, the premier of everybody."

It was with a similarly broad consensus that he was elected to the largely honorary post of President of the Republic in 1985. But the love of mischief which became increasingly prominent in the later years of his career nearly sank his term as head of state: in 1990 he revealed his involvement in Gladio, the Italian branch of the clandestine Nato-sponsored paramilitary organisations in action since the end of the Second World War intended as a front-line defence in the event of invasion from the East. His name was again cursed by left-wing demonstrators accusing him of state terrorism; he survived an attempt to impeach him but resigned a couple of months before the end of his presidential term in 1992.

The same year he declined Silvio Berlusconi's attempt to recruit him for Forza Italia, but as a senator for life Cossiga remained a Machiavellian player behind the scenes: he inspired the appointment of Massimo D'Alema as prime minister in 1998, the first and so far only ex-Communist to be Italian premier – allegedly because D'Alema was willing, unlike Romano Prodi, whom he succeeded, to commit Italy to the war in Kosovo.

Unpredictable to the end, Cossiga's final act was to refuse the honour of a state funeral.

Peter Popham

Francesco Cossiga, politician: born Sassari, Sardinia 26 July 1928; Prime Minister of Italy 1979-80, President 1985-92; married Giuseppa Sigurani (one daughter, one son); died 17 August 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments