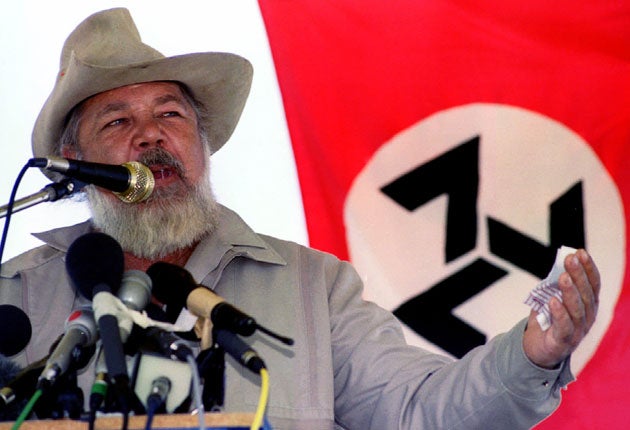

Eugène Terre'Blanche: Leader of the far-right AWB party who led the resistance to majority rule in South Africa

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The murder of Eugène Terre'Blanche, the notorious leader of the neo-Nazi Afrikaner-Weerstandsbeweging (Afrikaner Resistance Movement or AWB), who was bludgeoned to death, allegedly by two of his farm hands, following a dispute over unpaid wages, comes amid growing anxiety about crime in South Africa and what the opposition Democratic Alliance party has blamed on increasing racial tensions.

The South African white supremacist, who campaigned for a separate white homeland, came to prominence in the early 1980s around the same time that Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader of the far right party, Le Front National, was making headway in French elections. However, unlike Le Pen, Terre'Blanche's political career never really matched the grand rhetoric of his speeches, and was often marred by controversy and humiliation, caused partly by his womanising.

Born on a farm in the Transvaal town of Ventersdorp, about 100 miles west of Johannesburg, on 31 January 1941, Eugène Ney Terre'Blanche came from a family with a traditional Afrikaans background. His grandfather had fought as a so-called "Cape Rebel" for the Boer cause in the Second Boer War, against the British (1899-1902) while his father was a Lieutenant-Colonel in the South African Armed Forces.

The young Terre'Blanche attended Laerskool Ventersdorp and Hoër Volkskool in Potchefstroom, matriculating in 1962. He joined the South African Police Force before being transferred to a special unit guarding the residences of the state President and Prime Minister. Having reached the rank of warrant officer, he left the force after four years to become a farmer.

Disillusioned by the Westminster style of government and political discourse, Terre'Blanche, whose name means "white earth", founded the AWB with six others in 1973 in a garage in the Transvaal town of Heidelberg. The organisation first attracted public attention in 1979, when members tarred and feathered a prominent historian, Professor Floors van Jaarsveld, for publicly arguing that the Day of the Covenant, the anniversary of the Afrikaner victory (Battle of Blood River, 1838) over the Zulus, should be de-sanctified.

Terre'Blanche began to gain support through his skills as an orator. He modelled himself on Hitler and Mussolini, gestures included, his thunderous voice alternating between a roar and a whisper, mesmerising his followers and converting others. He played on people's fears and prejudices in the same way as his idols.

Violence was very much part of his fiery rhetoric. In addition, he played on Boer War memories, recalling the approximately 27,000 women and children who died in British concentration camps, and argued that Afrikaners should abolish political parties and seek to revive the pre-Boer war republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State in a new Boer Volkstaat. He wanted them to oppose what he regarded as the liberal policies of the then South African leader, John Vorster.

Initially, the AWB's paramilitary style – khaki or black-shirted men with side arms – seemed to appeal, and their numbers grew, as did Terre'Blanche's penchant for the dramatic. During the '80s, with large numbers being attracted to his rallies, he would arrive on horseback like a Boer general, sometimes alone, sometimes flanked by some of his militia.

The AWB were building arms caches and forming paramilitary units to oppose even moderate concessions by the government as black opposition to apartheid grew. Naturally enough, the organisation's strongest support was found in the rural communities of South Africa's north, with relatively few open supporters in urban areas. As far as Terre'Blanche was concerned the country had started on the slippery slope towards democracy, communism, black rule and the destruction of the Afrikaner nation in the 1980s, when P.W. Botha's government considered a constitutional plan allowing the country's Asian and coloured (mixed-race) minorities to vote for racially segregated parliamentary chambers.

With Nelson Mandela's release from prison in February 1990 and his support for reconciliation and negotiation with President F.W. de Klerk, who was heading towards free elections, Terre'Blanche threatened unrest and civil war. In 1991, when De Klerk addressed a meeting in Terre'Blanche's hometown of Ventersdorp, he led a protest. The Battle of Ventersdorp ensued between the AWB and the police, with a number of deaths. In 1993, in an attempt to disrupt the negotiation process, AWB fighters crashed an armoured vehicle through the plate-glass doors of the World Trade Centre in Kempton Park, near Johannesburg, while constitutional negotiations were in progress.

The AWB continued with further terrorist tactics, detonating bombs in urban locations including Johannesburg's main airport, in the run-up to South Africa's first democratic elections in 1994. Terre'Blanche's final attempt to block the transition to democracy came in March 1994. It was the final debacle for the AWB, who invaded Bophuthatswana, one of the nominally independent "homelands" which the apartheid government had set up in a gesture towards black self-determination, in an attempt to prop up the autocratic leader. The attempted coup resulted in three AWB militia being gunned down by opposition forces under the glare of TV cameras. For Terre'Blanche it was a PR disaster, ending any hopes of seizing power by force. April 1994 saw South Africa's first free elections, with victory for the ANC and Mandela, who became the country's first black President.

Terre'Blanche's reputation had also taken a battering following an alleged affair with the journalist Jani Allan which had shocked his conservative grassroots supporters while being lapped up by the rest of the country; she described him at one point as "a pig in a safari suit". He also had mishaps with his trademark arrival on horseback, falling off on a number of occasions. The AWB's membership declined and the organisation moved out of its Pretoria offices.

In 1998, Terre'Blanche accepted "political and moral responsibility" before South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission for the bombing campaign to disrupt the 1994 elections, in which 21 people were killed and hundreds injured. Following the end of apartheid, he and his supporters sought amnesty, which was granted by the Commission.

In 2000, Terre'Blanche was jailed for six months following an assault on a petrol attendant and setting his dog on him. Eventually his past caught up with him and in 2001, he was jailed for the attempted murder of a farm worker whom he beat so badly in 1996 that the man was left brain damaged. It was the type of rhetoric he had espoused over the years. Upon his release in 2004, he had become a born-again Christian and spent much of his time writing poetry and living on his farm in anonymity.

In 2009, however, the ever bullish Terre'Blanche proclaimed that he had revived the AWB after several years of inactivity and that it would join with like-minded forces to push for secession from South Africa. "The circumstances in the country demanded it," he told the South African papers. "The white man in South Africa is realising that his salvation lies in self-government in territories paid for by his ancestors." Much of this was seen as more hot air from a political figure who had promised so much but delivered so little.

Martin Childs

Eugène Ney Terre'Blanche, white supremacist leader, born Ventersdorp, South Africa 31 January 1941; married (one daughter); died Villana, near Ventersdorp 3 April 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments