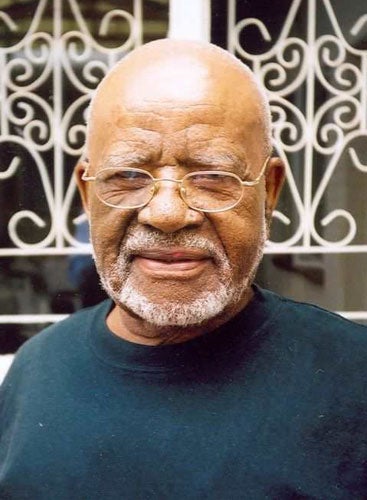

Es'kia Mphahlele: Founding figure of modern African literature who became a powerful voice in the fight for racial equality

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Es'kia Mphahlele was one of the founding figures of modern African literature. Though a novelist and short story-writer of distinction, he will almost certainly be remembered most for the autobiographical Down Second Avenue, published in 1959 when the world's conscience was first being pricked by South African writers protesting at the apparently indomitable system of apartheid.

Mphahlele was born in Marabastad, Pretoria, in December 1919. He never forgot the hard work of his mother and his aunt, who together provided the means for him to break from the slums of Pretoria and his early experience as a herdboy nearby. They paid for him to go to St Peter's Secondary School in Johannesburg. From there he went to Adams College in Natal. He registered as an external BA, and later MA, student at the University of South Africa, laying the ground for his graduation years later, in 1968, with a PhD from the University of Denver.

His plan was to become a secondary-school teacher, but the government banned him from doing so because he had publicly criticised the Bantu Education Act. Indeed, he served a short prison sentence for his opposition to the Act. Instead he began his adult working life as a messenger. He decided that the best thing to do was to return to Pretoria, where he was taken on by the monthly magazine Drum. It was as a journalist that he first realised how powerful a tool the written word might be in the struggle for his people's self-respect. He used his given name, Ezekiel, rather than Es'kia, which he only adopted in 1977 on his return from exile.

Mphahlele struggled to find a literary voice, for the demands of instant delivery nearly did for him as a serious writer. "My prose was suffering under severe journalistic demands and I was fighting to keep my head steady above it all," he recalled. "I felt like a slow-footed heavyweight, wanting to be sure of every punch, in a ring which required a disposition to duck and weave and gamble and love the game or quit." Nevertheless, a collection of short stories, Man Must Live, was published in Cape Town as early as 1947. His intention of being a serious writer was there from the start, though it was to be 14 years before the arrival of a second collection, The Living and Dead (1961), again published by an indigenous African publishing house.

Mphahlele joined the African National Congress in 1955, though he was never a key player in its affairs and parted company with it some years later. By this time his protests at the iniquities of the South African government had become so fervent that the only alternative to another prison sentence was to go in to exile, a route that so many of his generation felt obliged to take. On 6 September 1957 Mphahlele left South Africa for Lagos, Nigeria, where for a while he fulfilled his ambition to teach secondary-school children. The University of Ibadan, however, offered him a post as Lecturer in English Literature in its Department of Extra-Mural Studies.

It was the start of an itinerant existence. In his 20 years outside his homeland he never settled anywhere for long. In Paris, he directed the African programme at the Congress for Cultural Freedom. He also lived in London, Nairobi, Denver, Lusaka and Pennsylvania. He gave good service in each place, but did not make a real home in any of them. Eventually the lure of South Africa proved irresistible. In 1977, long before the main wave of exiled writers returned, he went home, incurring some hostility among those who stayed away.

He discovered that the government still interfered, vetoing a professorial appointment which had been offered at the University of Limpopo in Turfloop. Instead he became an inspector of schools at Lebowa, only seven miles from where he had grown up; he lived the last 30 years of his life as much as possible in the landscape of his heart. However, in 1979, he became the first black man to be offered a chair by the University of Witwatersrand, and set up a programme of teaching African literature. He retired as Emeritus Professor of African Literature in 1988 but remained associated with Wits for the rest of his life.

Mphahlele's main published works often draw from autobiographical experience. Down Second Avenue is one of the classic African expositions of growing up in hardship. His third book of stories, In Corner B (1967), reflected some of his experiences and encounters before and after exile, including the final tale, "Mrs Plum", one of the most damning indictments of white liberalism in South Africa; a revised edition appeared as a Penguin Modern Classic in 2006.

The 1971 novel The Wanderers reflects his own nomadic life at the time. Another novel, Chirundu (1979), drew from his observation of the dynamics of politics in Zambia, though it purports to be set in an imagined country. Mphahlele was also a trenchant literary critic. The African Image (1962) wrestled with issues of African identity, countering the Francophone concept of "negritude". Voices in the Whirlwind and Other Essays (1972) was a bold collection of six pieces positioning himself in relation to the burgeoning discourse of African aesthetics.

Handsome in his prime, snowy white and venerable in age, Es'kia Mphahlele had a natural gravitas. To some extent this disguised his internal demons. He did not find writing easy and there were long silences. He often felt misunderstood and he certainly found it hard in the late 1970s to adjust to a South Africa in which injustice seemed even more entrenched than when he had moved abroad 20 years before. Perhaps he knew that his place in literary history would be as a powerfully representative voice in the struggle for freedom, not as the creator of a masterpiece. One consolation was his long marriage to Rebecca Nnana Mochedibane, and his five children, four of whom survive him.

Alastair Niven

Ezekiel Mphahlele (Es'kia Mphahlele), writer and teacher: born Marabastad, South Africa 17 December 1919; Professor of African Literature, University of Witwatersrand 1979-88 (Emeritus), Head of African Literature 1983-88; married 1945 Rebecca Nnana Mochedibane (died 2004; four sons, and one daughter deceased); died Lebowakgomo, South Africa 27 October 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments